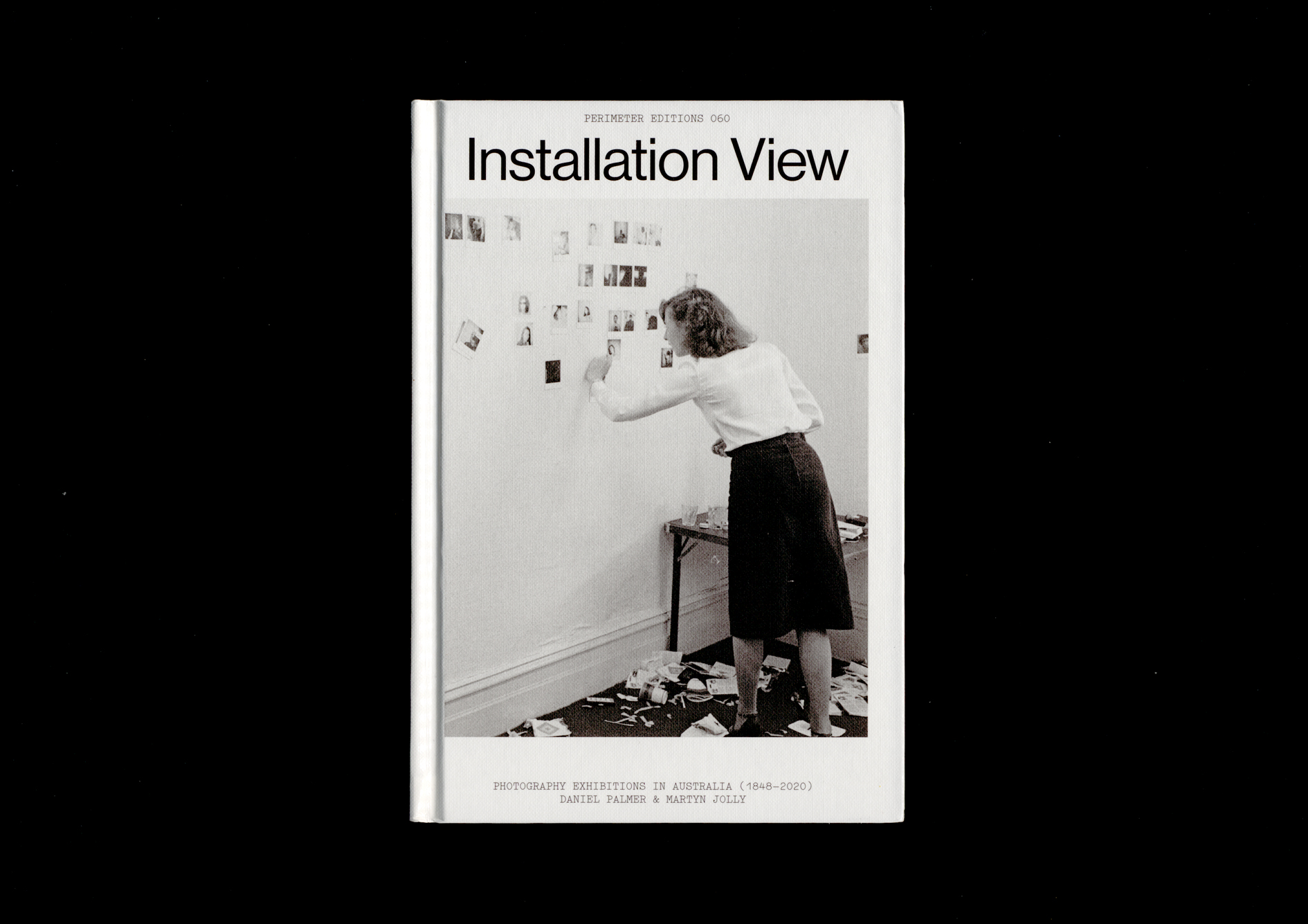

(Installation View, pp. 7–18)

This book provides a new account of photography in Australia from the colonial period to the present day, viewed through its most important exhibitions and modes of collection and display.1 Previous histories of what we collectively understand as ‘Australian photography’ have used different lenses: artistic style, the social politics of Australia, the idea of the nation, and a particular relation to light, to name only some of the most significant.2 Other histories are focused around a specific collection of photographs.3 By and large, these valuable accounts – which we have drawn on here – have been told through the lens of individual photographers and specific images. By contrast, in this publication we explore the constantly mutating forms and conventions through which photographers and curators have selected and presented photographs to the public. Specifically, we chart the ‘evolution’ of photography exhibitions as necessarily in dialogue with developments in the technologies of photographic image-making and their social context – including daguerreotype displays, colonial world exhibitions, pictorialist salons, documentary ‘photo-essays’, postmodern deconstructions and contemporary digital displays.

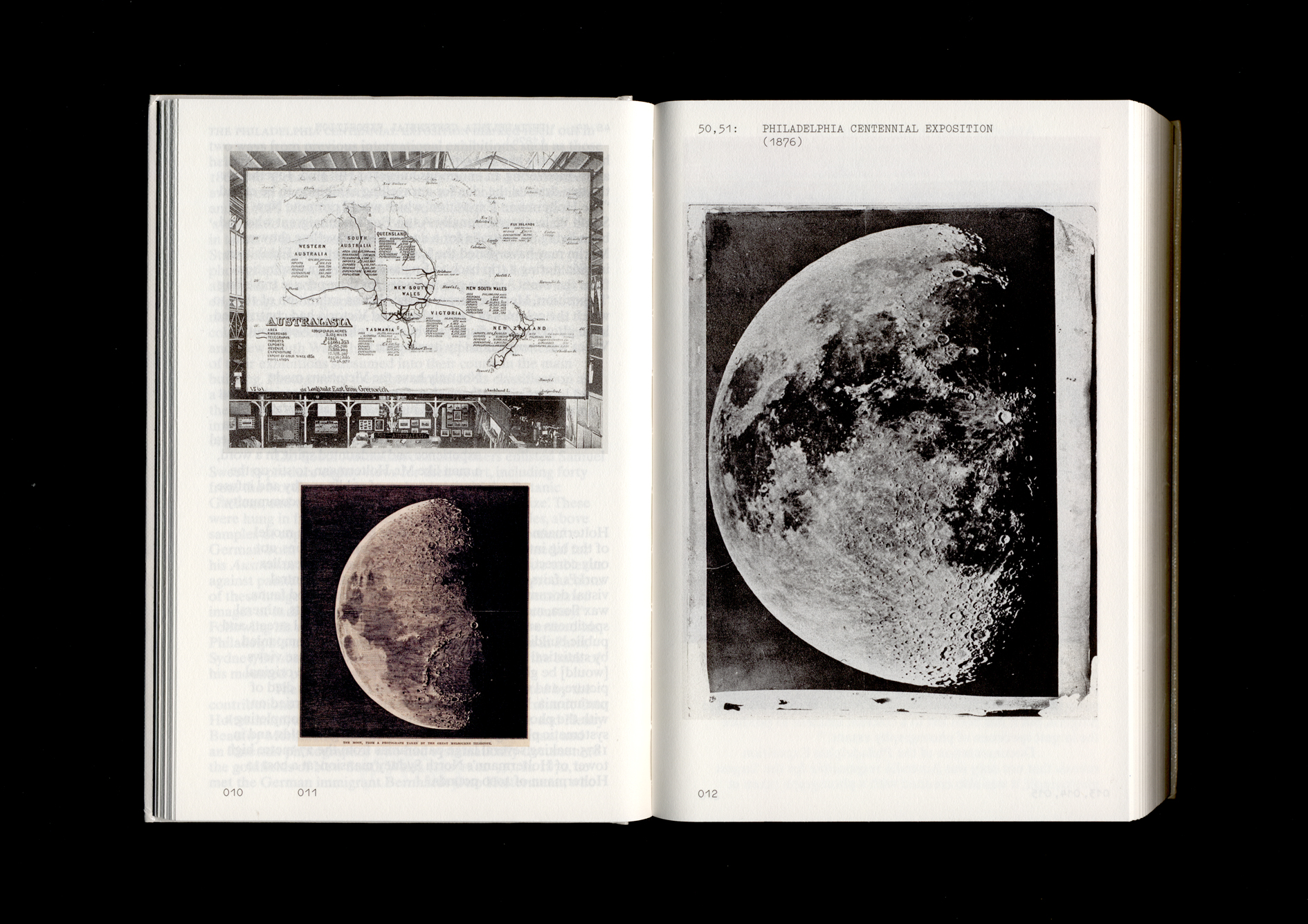

Along the way, this book details a number of likely Australian ‘firsts’: the first large-scale daguerreotype exhibition (in Sydney, 1848); the first ‘purely photographic’ group exhibition (in Melbourne, 1884); the first solo exhibition by an art photographer in a gallery setting (Harold Cazneaux, 1909); the first solo exhibition by a female photographer (Ruth Hollick, 1928); the establishment of the first department of photography at a state art gallery and the first exhibition there (National Gallery of Victoria, 1967 and 1968 respectively); the first female photographer at a state art gallery (Sue Ford, 1974); the first permanent photography centre (Australian Centre for Photography, 1974); the first time photography was shown in a major survey of contemporary Australian art (Perspecta, 1981); the first Australian photographers in the Biennale of Sydney (4th Biennale of Sydney, 1982); the first photographer to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale (Bill Henson, 1995); the first group exhibition of Indigenous photography (NADOC, 1986); and so on. We chronicle these moments not to establish precedence, but to demonstrate the shifts in how photography has been conceptualised, who has produced it, and the kinds of spaces in which it has been shown over the last 170 years, constantly morphing like the medium itself.

Which is not to say that historical evolution is linear. Some key issues for photographers and viewers alike seem to keep re-emerging in new ways. For instance, this book throws into relief the way photographers and curators have always grappled with scale – specifically, how to enlarge an image so that it commands attention in an exhibition space. They have also always faced the related challenge of the medium’s tendency to inspire the production of large sets rather than singular images, so they have constantly wrestled with the problem of presenting substantial numbers of smaller multiple or sequential images to audiences moving through exhibition spaces. Another persistent issue we reveal is the photograph’s continual symbiotic reliance on other media for actualisation – not only the model of painting, but also print and reproduction technologies, graphic design, industrial design, copywriting and retailing. Because all these fundamental issues have been so persistent from the beginning, looking closely at historical installations and exhibitions can radically refresh our understanding of current exhibition practices. Indeed, Australian art museums have frequently turned to the nineteenth century to complicate the contemporary moment, and vice versa.4 In doing so, they often mime the logic of Australian library collections, for whom nineteenth-century photography has proved fundamental – from the State Library of New South Wales’ first acquisition of portraits from Freeman Studios in 1953, to its recent high-resolution re-digitisation of the Holtermann collection (see page xxx). Colonial Australia grew up with photography, and through perpetual re-archiving and re-exhibiting, the nineteenth century is constantly remade anew.

The notion of what constitutes ‘Australian photography’ is continually reshaped through exhibition practice. Right from the beginning, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the exact quality that made a photographer, a photograph, or a photographic style ‘Australian’ was open to competing definitions. Despite Australia’s geographical location, individual photographers have always been surprisingly mobile, even before the ‘jet age’ of frequent overseas travel. Many photographers we think of as ‘Australian’ maintained strong international connections, while other photographers who were only ‘passing through’ Australia made significant impact. We have made an effort to include key overseas exhibitions involving Australian-based photographers, particularly when they operated in an ambassadorial role, and we refer to some key exhibitions of international photography in Australia that have had a demonstrable impact on local practice. But photographs are even more mobile than photographers. As our history underlines, exhibitions have continually brought together photographs from many different places, so the porosity of national boundaries and Australian visual culture more broadly is starkly evident in its photographic exhibitions. By looking at the shared space of the gallery it becomes clear that the catalysing of photographs taken in Australia with those taken overseas or by travelling photographers spending only a few months or a few years in Australia has been a powerful driver to the development of what we call ‘Australian photography’.

There are three interrelated motivations for this book. The first is that photography’s historical evolution is both distinct from, and interdependent with, traditional art mediums such as painting or sculpture. Furthermore, there are qualities in the medium of photography that have produced particular outcomes in its display and collection that warrant attention.5 Relatively recently, in the 1980s, photography moved from the periphery to the centre of the art world. Thus, in 2017, one of Australia’s best-known living artists, Tracey Moffatt, represented Australia at the Venice Biennale, becoming only the second artist after Bill Henson in 1995 to represent Australia with a major suite of photographs. Both artists consolidated their success in the 1980s. In 2017, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) quietly celebrated fifty years since the founding of the first Department of Photography in Australia. But photography has been so successful at becoming art that the place of photography departments in Australian art galleries appears to have become unmoored. Inside our state galleries, photography is now widely presented in major exhibitions of contemporary art. Many of Australia’s major artists work with a variety of mediums including photography, and it seems to make little sense to confine their work to a dedicated photography gallery. This moment coincides with the departure of a highly significant first generation of photography curators (Gael Newton at the National Gallery of Australia, Judy Annear at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Isobel Crombie at the NGV), and a reluctance on the part of Australian art institutions to invest in medium-specific curators or galleries. Indeed, hard-won spaces dedicated to the exhibition of photography in our state galleries have been abandoned in recent years, as institutions favour non-medium-specific spaces brought on by the so-called ‘post-medium condition’ of contemporary art.6

From a certain perspective, photography is now simply one among countless other forms of art or image making. But unfortunately, what today’s supposedly ‘successful’ integration of photography into the art museum all too easily elides is that photography’s place there has always been unstable, its ambiguous status as object and information continually threatening the grounds of the art museum’s hierarchies and collection policies.7 This instability has manifested itself in different ways during different periods, from the very different collecting practices of the library to the disruptive force of the digitally networked image. The photograph’s multiple and ambiguous presence as image and object continues to complicate its place in the art museum, even as the full potential of this slippage is arguably unrealised – and is now complicated further by the notion of the Instagram-friendly museum, in which exhibitions are designed for circulation as photographs on social media platforms.

The second motivation for this book is that exhibitions have always been important vehicles for the promotion and innovation of photographic practice. They have long been the place where conventions have been tested, and arguments about photography made and played out in their public reception. From the first World Expositions and ‘conversaziones’ of the mid-late nineteenth century, photography exhibitions have been places where photographic technology, photographic images, photographers and audiences were brought together to promote the technological advances in the medium as part of a wider demonstration of the economic and social advances of the colony. Exhibitions underline that the social world within which photographers work is critical, and that among the primary audience for exhibitions are other photographers. With the emergence of camera clubs and Australian pictorialism around the time of Federation, aspirations for photography as art have been a primary – but not the exclusive – driver for exhibitions of photography. The annual exhibitions of the amateur associations were designed to encourage competition and technical improvement, as well as ‘stimulate emulation and so contribute to the higher development of the art’.8 And by the 1920s, the most ambitious exhibitions – adopting the stripped-down neutral colours of hessian walls on the road to the modernist white cube – were knocking on the door of state art galleries. Despite ongoing efforts, this battle was not won in Australia until the establishment of photography in state art museums in the early 1970s, in the context of a much-vaunted ‘photo boom’ when, as Helen Ennis has pointed out, the baby-boomer generation turned to photography for its contemporaneity in the context of countercultural energy and unprecedented levels of state and corporate support for the medium’s artistic aspirations.9 That period saw the proliferation of art schools teaching photography and ‘artists using photography’, as well as commercial and independent photography galleries.

Yet the display of photographs as art objects is only part of the story. Throughout the history of Australian photography, we find a wide array of significant exhibitions that have served purposes other than that of the purely aesthetic. If exhibitions, by their nature, seek to advance new ideas and educate audiences, exhibitions of photography have been particularly engaged in forms of persuasion and advocacy – whether for the promotion of colonial wealth in the nineteenth century, creating a new sense of national identity after the federation of the colonies in 1901, or memorialising Australia’s profound involvement in World War I. Likewise, photographers took it upon themselves to use photography exhibitions not only to educate the public about its potential as an art form, but to appeal to industrial clients and contribute to a new understanding of humanity in the post-war period through social documentary. Since the 1970s, photography exhibitions have also been centrally involved in campaigns to raise political awareness around issues such as the environment, Indigenous land rights and the representation of women. Institutional support structures have reflected these different purposes for which photography exhibitions have been mounted – the salon and the art gallery on the one hand, and the library and the archive on the other. In 1971, the National Library of Australia clarified its collection policy: it would only collect photographs as examples of photographic art and technique from the period up to 1960, leaving post-1960s ‘art for art’s sake’ photography to the new state and federal gallery photography departments.10 In short, library collecting would focus on the photograph as a document of Australian life rather than an artistic activity. More recently the distinctions have blurred again as library practice has evolved.11

Our third and final motivation concerns photography’s ongoing transformation into digital forms. By focusing on exhibitions, this book draws attention to the materiality of photography, from the photographic processes which produce photographs in all their various forms, to the display strategies that bring different audiences to them. Exhibition practices underline the fact that photography has always been a reproducible medium – circulated as postcards and half-tone reproductions in magazines and books since the late nineteenth century, and more recently via digitally enabled screens. For, today, two decades into the twenty-first century, photography is overwhelmingly produced and experienced on networked screens, which become exhibition spaces in themselves.12 The physical print, meanwhile, is becoming a special category in photography. In contemporary practice, prints are increasingly limited to art photography, destined for a gallery space, to be mounted as a physical object on the wall. Beyond this, prints are now largely confined to historical archives as a document of history. Digitised and searchable, these same archives have themselves become newly accessible and, indeed, exhibitable in different ways. The materiality of the physical print nevertheless remains important for many contemporary artists, the art market and art galleries. Indeed, our history reveals the persistence of the photograph as a ‘material object’, in the form of daguerreotypes, photograms and other anachronistic but embodied methods of image-making such as black-and-white darkroom prints, as well as how artists such as Brook Andrew and Patrick Pound have innovated the use of archival and vernacular photographs in their exhibition making.

A set of questions now emerge: what is the status of the physical photography exhibition in an age when photography more broadly is experienced as flickering data on handheld, liquid crystal display screens? Are physical exhibitions of photography now simply an exercise in ‘heritage’ media, in which we are witness to the now almost redundant craft of photographic printing? The ‘photograph as art object’ that has been collected now for several decades is also now facing a conservation crisis, as images collected in the 1970s and 1980s are literally fading beyond recognition. Is the museum a legitimate place for the spectacle of large-scale awe-inspiring prints, dismissively dubbed ‘museum photography’ by one British critic?13 As this book reveals, these questions all benefit from knowledge of historical precedents. In the past, exhibition design for photography exhibitions in Australia often surprisingly mobilised multiple images, at multiple scales, in three-dimensional architectonic space, rather than the now museum-conventional row of framed prints on the wall. The remarkable dynamism of Helmet Newton and Wolfgang Sievers’ exhibition at a Melbourne hotel in 1953 even evokes (surely coincidentally) Marcel Duchamp’s infamous installation for the 1942 First Papers of Surrealism exhibition in New York, in which he criss-crossed a space with a ‘mile of string’. In this respect, our focus on exhibiting photography provides a way of analysing the protean nature that photography has always had, but which has been disguised by auteurial or stylistic historiographic approaches. Today, perhaps the key question facing the photography exhibitor or curator is simply: how can the exhibition offer a different way of viewing photography to the conventional ‘swipe and like’ culture the medium itself forms a part?

The Structure of the Book

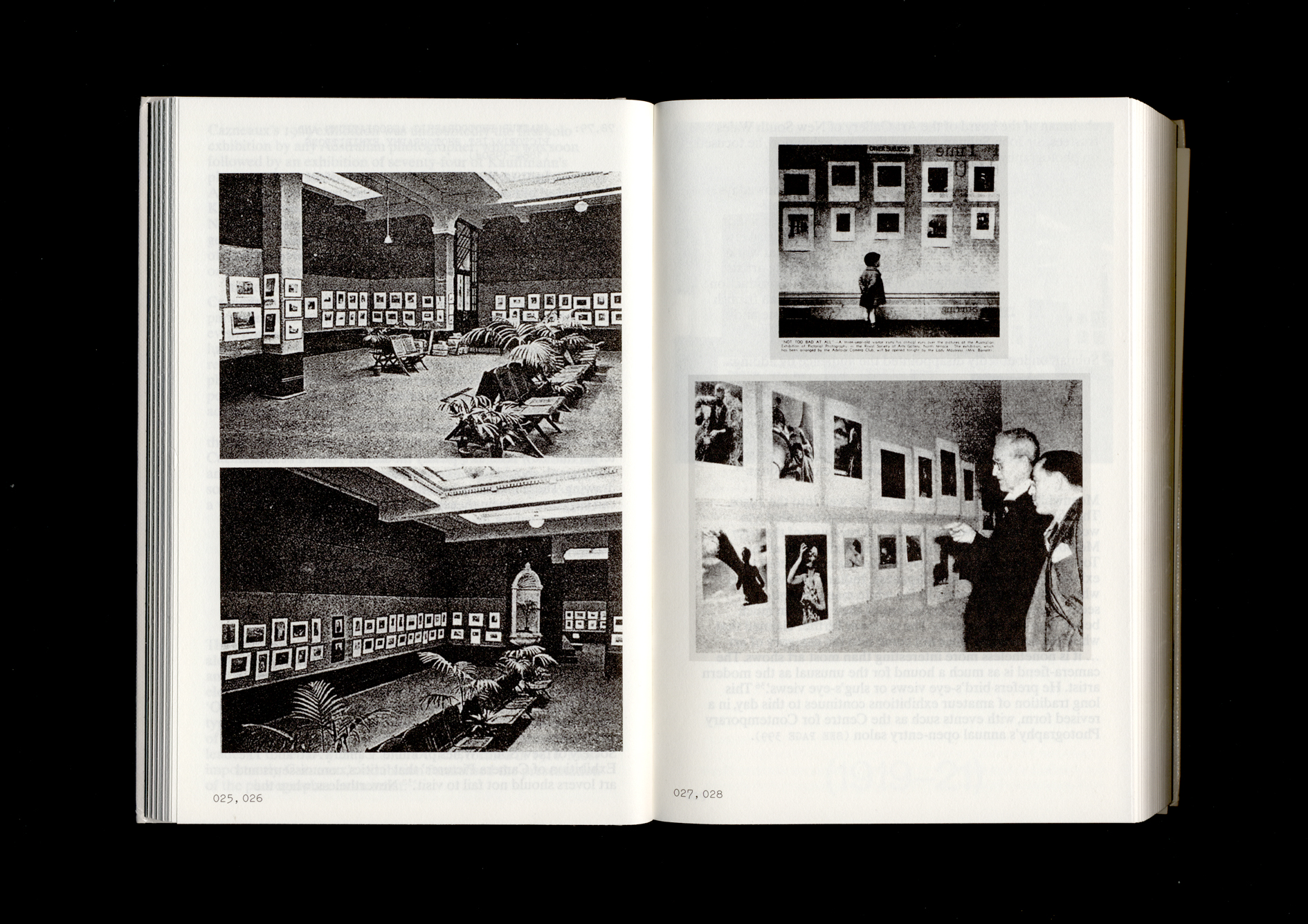

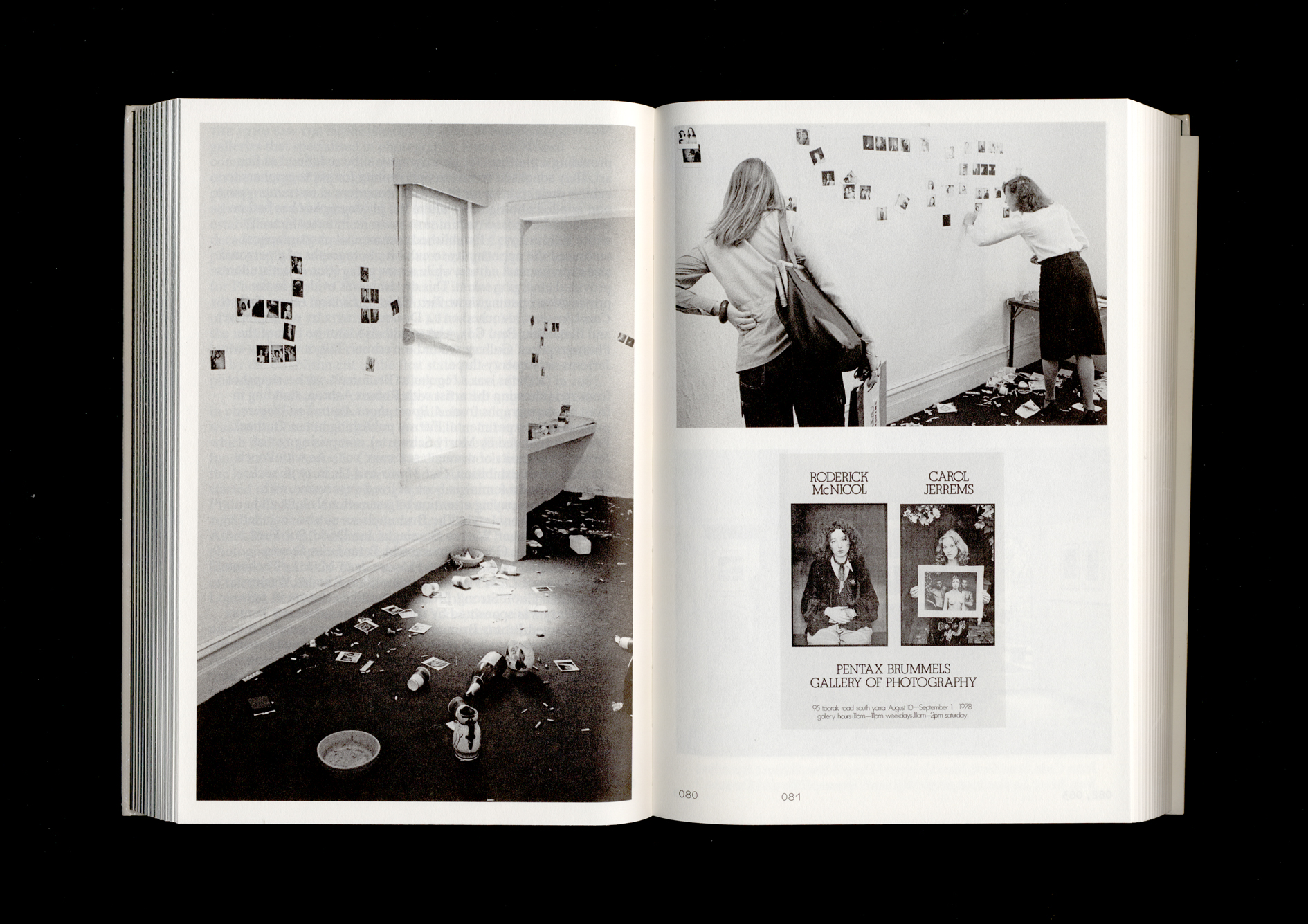

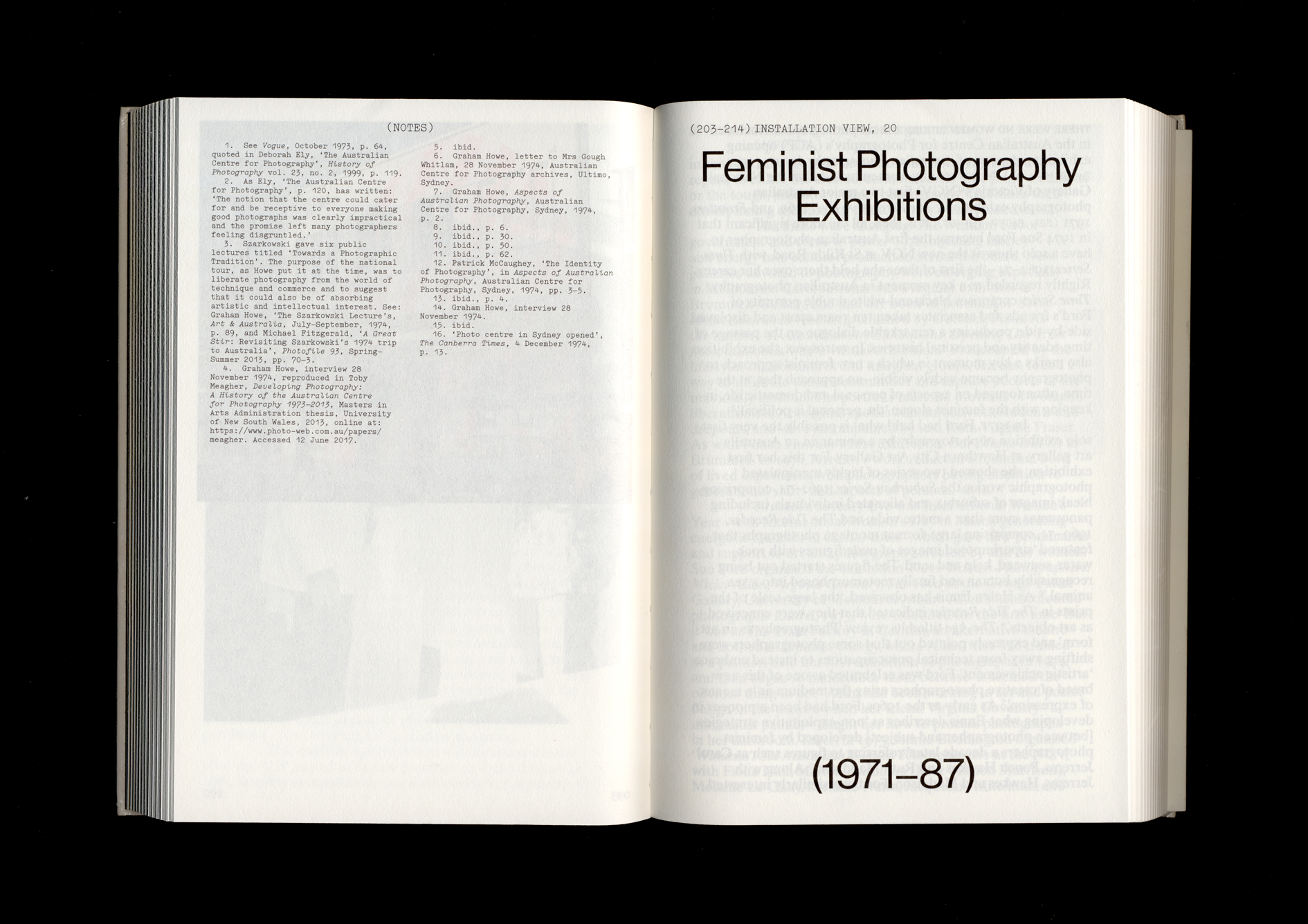

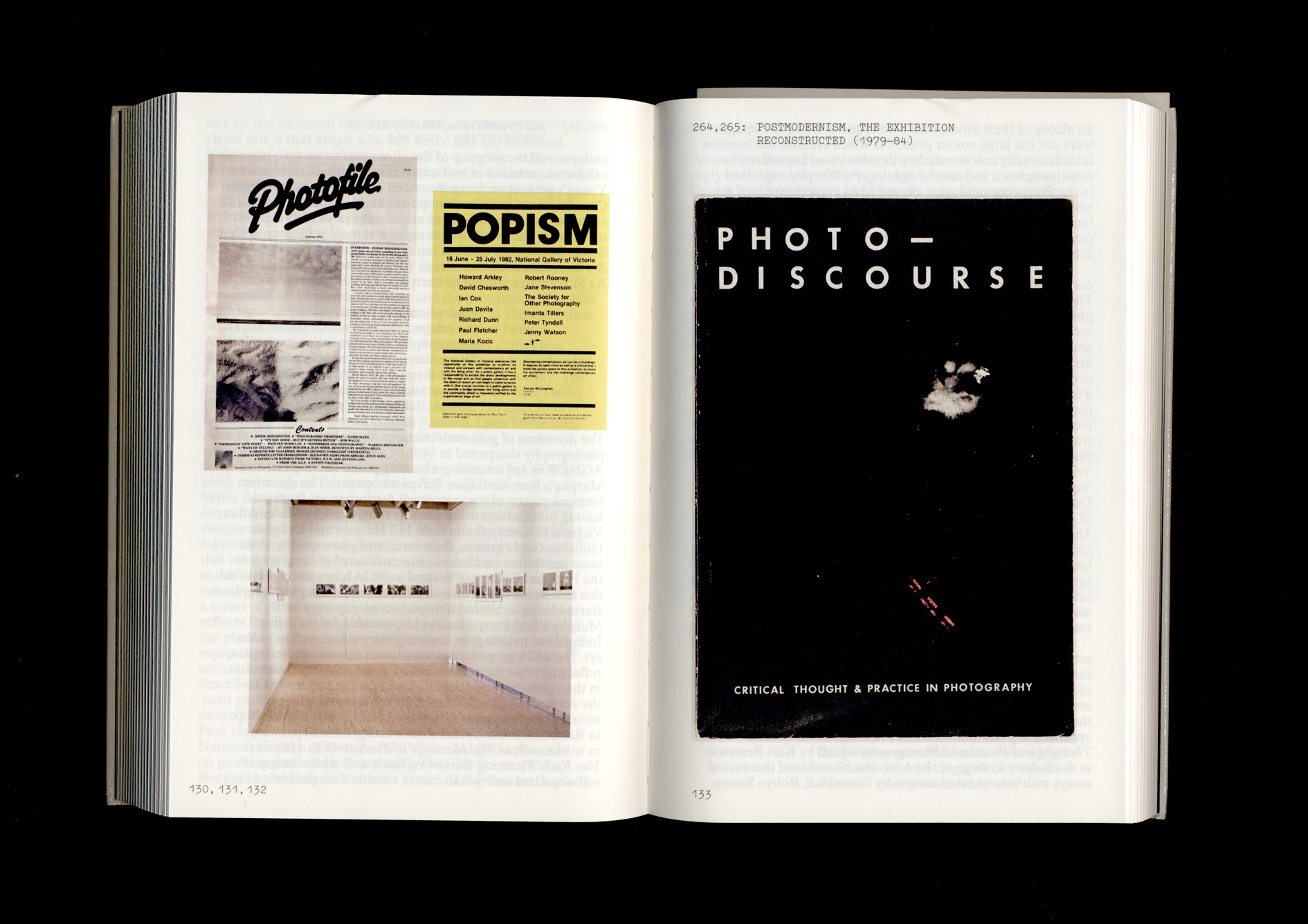

This book is driven by installation photographs sourced from institutional and private archives, both local and international. Presented as a chronological account, the images are supplemented by mini-essays that we have come to call ‘vignettes’. Something more than annotations and less than fully developed essays, these function as brief evocative descriptions of key episodes or themes in the history of Australian photography exhibitions. We have drawn on existing histories of photography but generally avoided repeating familiar narratives published elsewhere. Through primary research in the form of exhibition reviews, we have attempted to grasp the reception and significance of the exhibitions in their historical moment. This contemporary writing from newspaper reviews and journals provides vital firsthand context. In these vignettes we have included photographic documentation of exhibitions as well as artefacts related to the exhibitions such as promotional posters and catalogues. Through the detail of exhibitions, readers can traverse the material richness of Australian photography.

Obviously, we have not been able to provide an exhaustive account of every significant photography exhibition ever staged in Australia. No doubt, some readers will disagree with our selection and identify omissions that we could have included. The final selection has been determined by a combination of factors – most importantly the representativeness of the exhibition, our sense of the significance of the exhibition for how Australian photography was and would be produced, and the availability of informative installation views. From a practical point of view, writing the history of exhibitions presents a conundrum. Unlike the individual images that have conventionally preoccupied art historians, exhibitions are more like performances – they are experiential and ephemeral, involving bodies in space at particular moments in time. Documentation is unavoidably partial. Inevitably, in place of exhibitions, the individual photograph – as an apparently stable art object – becomes the more prominent record, and the original context for its public display fades from view. As a result, the crucial role of the exhibition’s context in the reception of a photograph is forgotten. Over and again, we find that exhibition prints and their layout are quite distinct and different from the photographs that are later collected and then become known through later displays and reproductions. In some cases, the ambitions of photographers themselves, pushing the technical limits of the medium for the purposes of an exhibition, made a work’s preservation near impossible. Other photographs have perished in transit or storage. Exhibited photographs not collected or published are easily forgotten. But exhibitions are critically important because it is through them, rather than individual photographs, that audiences first experience the photograph in an aesthetic and often national context. Modernist exhibition design, for instance, was instrumental in performing photography’s potential to see the world differently.

Aside from bringing to light a whole new understanding of familiar material – seeing the often surprising early installations of how now iconic photographs were first presented – the lens of exhibition practice brings different types of practice into view. Crucially, the lens of the exhibition allows us to consider photography as a social and political phenomenon within the public sphere, rather than treating individual photographs as representative of aesthetic styles within different genres, or biographical markers for individual photographers. Photographers themselves have been the primary organisers and innovators of exhibitions – given that the era of the professional photography curator only stretches back to the early 1970s – but this book also focuses attention on the institutional and historical processes through which photographs have been selected (and more recently curated) into an ‘Australian photography’. Directly and indirectly, this book addresses the powerful role that institutions – whose policies and imperatives are often deeply influenced by the advocacy of photographers as well as overseas trends – have played in forming Australian photography. For example, we pay attention to the rise of the photography gallery as a crucial, period-defining contemporary art space, notably in the shape of the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney (established 1974). And incidentally, as part of the story, this book illustrates changing fashions in the history of Australian architecture and design.

This is both a sourcebook for key exhibitions in the history of Australian photography and a parallax view that hopes to enrich and revise our understanding of what ‘Australian photography’ is. We have taken a step sideways to consider Australian photography not just as a story of ‘great photographers’ and ‘great photographs’ or a succession of different styles, but as overlapping layers of engagement between publics, spaces, institutions, photographers and curators. Our hope is that our little history – with its conjoined histories of exhibiting and collecting at libraries, art museums, galleries and online – not only sheds new light on past practices, but also provide the context through which to understand opportunities for new ways of curating and presenting photography in Australia, today and into the future.

-

This book emerges out of several years of research into the history of Australian exhibitions, funded by an initial grant from the Australia Council and then the Australia Research Council Discovery Project, ‘Curating Photography in the Age of Photosharing’ (2015–18). An online timeline is available via the related website (www.photocurating.net). The project also involved two roundtable discussions with curators of photography in an effort to grapple with the new challenges facing the mounting of photography exhibitions in the twenty-first century. ↩

-

Respectively, these approaches have been adopted by Gael Newton, Anne Marie Willis, Helen Ennis and Melissa Miles. See Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988; Anne-Marie Willis, Picturing Australia: A History of Photography, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1988; Helen Ennis, Photography and Australia, Reaktion Books, London, 2007; Melissa Miles, The Language of Light and Dark: Light and Place in Australian Photography, Power Publications, Sydney, 2015 ↩

-

See, for example: Alan Davies’s An Eye for Photography: The Camera in Australia, 2004, at the State Library of New South Wales or Helen Ennis’s Intersections: Photography, History and the National Library of Australia, 2004. ↩

-

An early example is Portraits of Oceania, curated by Judy Annear at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1997. ↩

-

Despite the proliferation of curatorial discourse and exhibition histories in recent years, very little of it is concerned with the specificity of individual mediums. Particular qualities pertaining to the display of photography barely register in contemporary debates around curating. This is an extraordinary oversight, given that photography has long been theorised as a radical challenge to the traditional art object and art museum. From Walter Benjamin’s ‘withering of aura’ to André Malraux’s ‘museum without walls’, and of course writers associated with postmodernism who took up those ideas (such as Douglas Crimp), photographs challenge the very notion of museum practice. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version’, in Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (eds.), Selected Writings: Volume 3, 1935–1938, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 101–33. ↩

-

Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Thames & Hudson, New York, 1999. ↩

-

As Douglas Crimp argued in the late 1970s, the inclusion of photography within the canon of modernist art practice operates to exclude most photography by virtue of its emphasis on authorship and originality. Douglas Crimp, ‘The museum’s old/The library’s new subject’, in Richard Bolton (ed), The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.,1989, pp. 3–13. See also: Andrew Dewdney, ‘Curating the photographic image in networked culture’, in Martin Lister (ed.), The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, second edition, Routledge, London, 2013, pp. 95–112. ↩

-

The Advocate, 1 December 1894, p. 15. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, ‘Contemporary photographic practices’, in Gael Newton (ed.), Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, ‘Integral to the vision: A national photographic collection’, in Peter Cochrane (ed.), Remarkable Occurrences: The National Library’s First 100 Years, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2001, p. 210. ↩

-

Alan Davies’s 1989 exhibition at the State Library of New South Wales, At Work and Play: Our Past in Pictures exemplifies the first approach of collecting photographs as historical documents. Michael Aird’s 2012 exhibition at the State Library of Queensland, Transforming Tindale, where the artist Vernon Ah Kee responded to anthropological photographs, exemplifies the second approach of using contemporary art to examine history. ↩

-

We completed this book during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when galleries and festivals have been forced to reconfigure their public modes of communicating, and the photograph has become more distributed, performative and precarious than ever. ↩

-

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Museum Photography and Museum Prose’, New Left Review, 65, September–October 2010, pp. 93–125. ↩