(Installation View, p. 29–36)

In the 1860s, Victoria was a colony of burgeoning wealth generated by the discovery of gold a decade earlier in 1851. The congested opulence of the great international exhibitions of Britain and Europe, particularly London’s International Exhibition of 1862, inspired the colony to host the first Australian Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne during 1866–67. Six Australian colonies brought their commodities, botany, geology and mechanical industry, along with their craft, painting and photography, to the Victorian capital. The colonies of New Zealand, Mauritius, New Caledonia and Batavia also sent displays.1

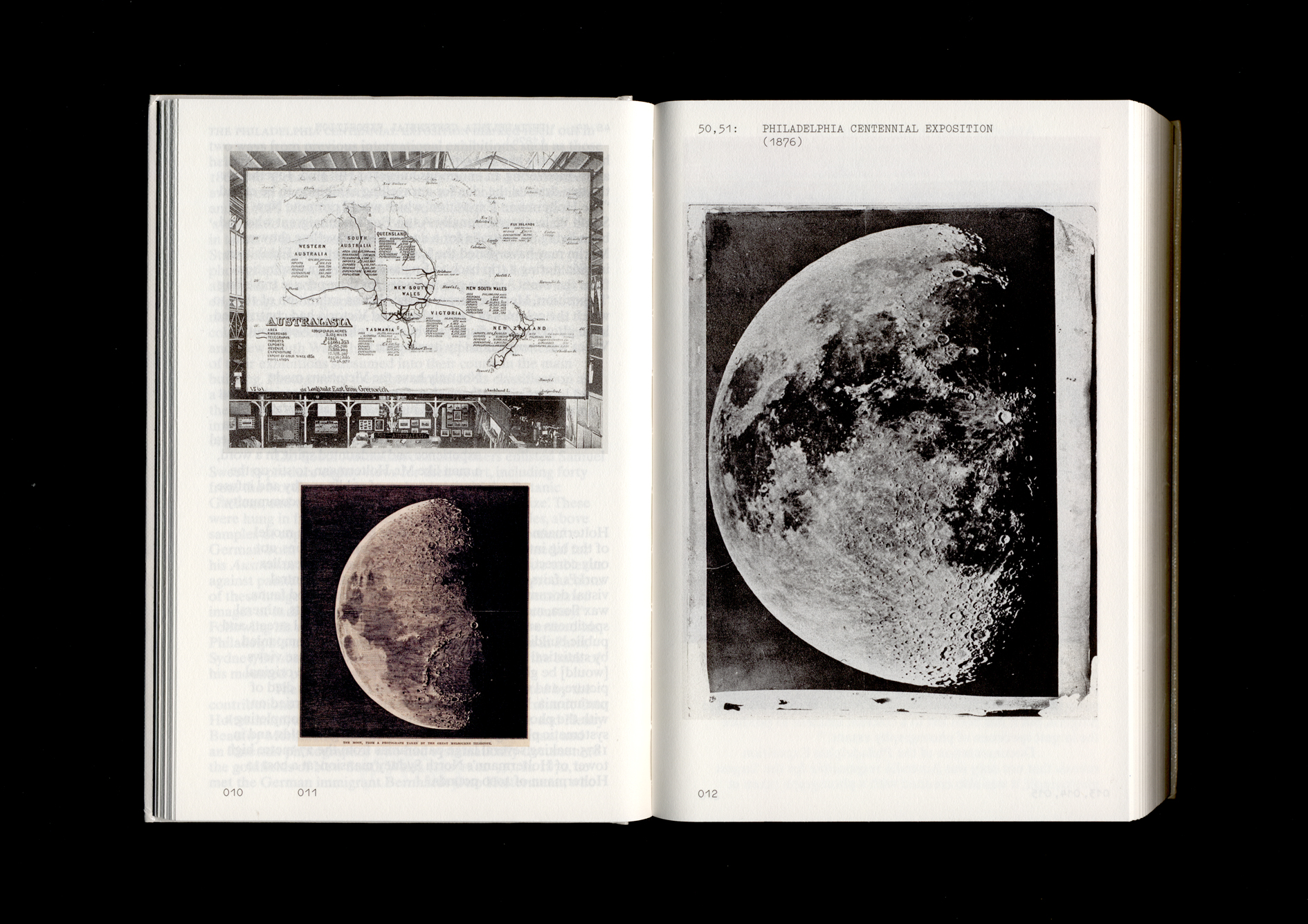

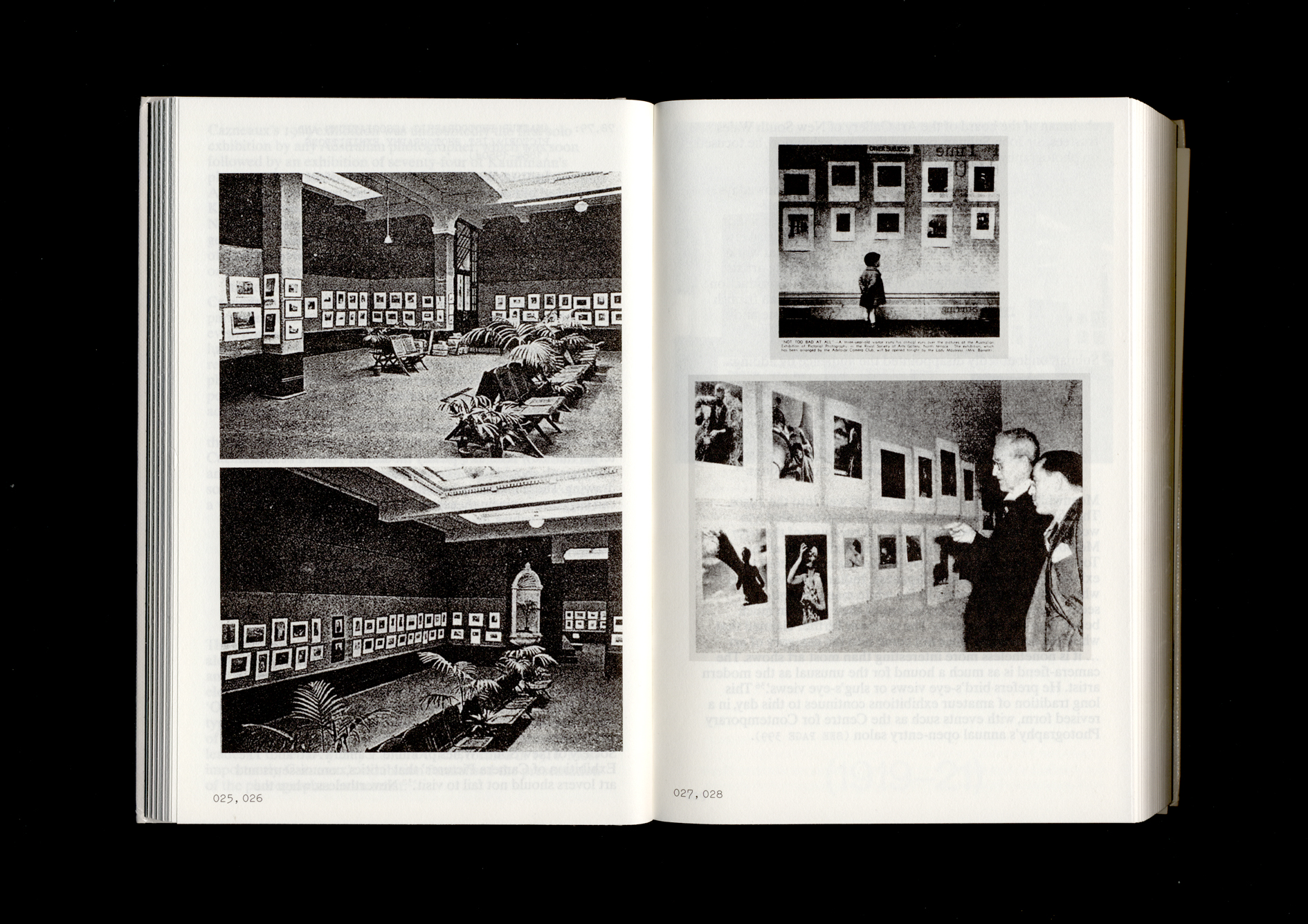

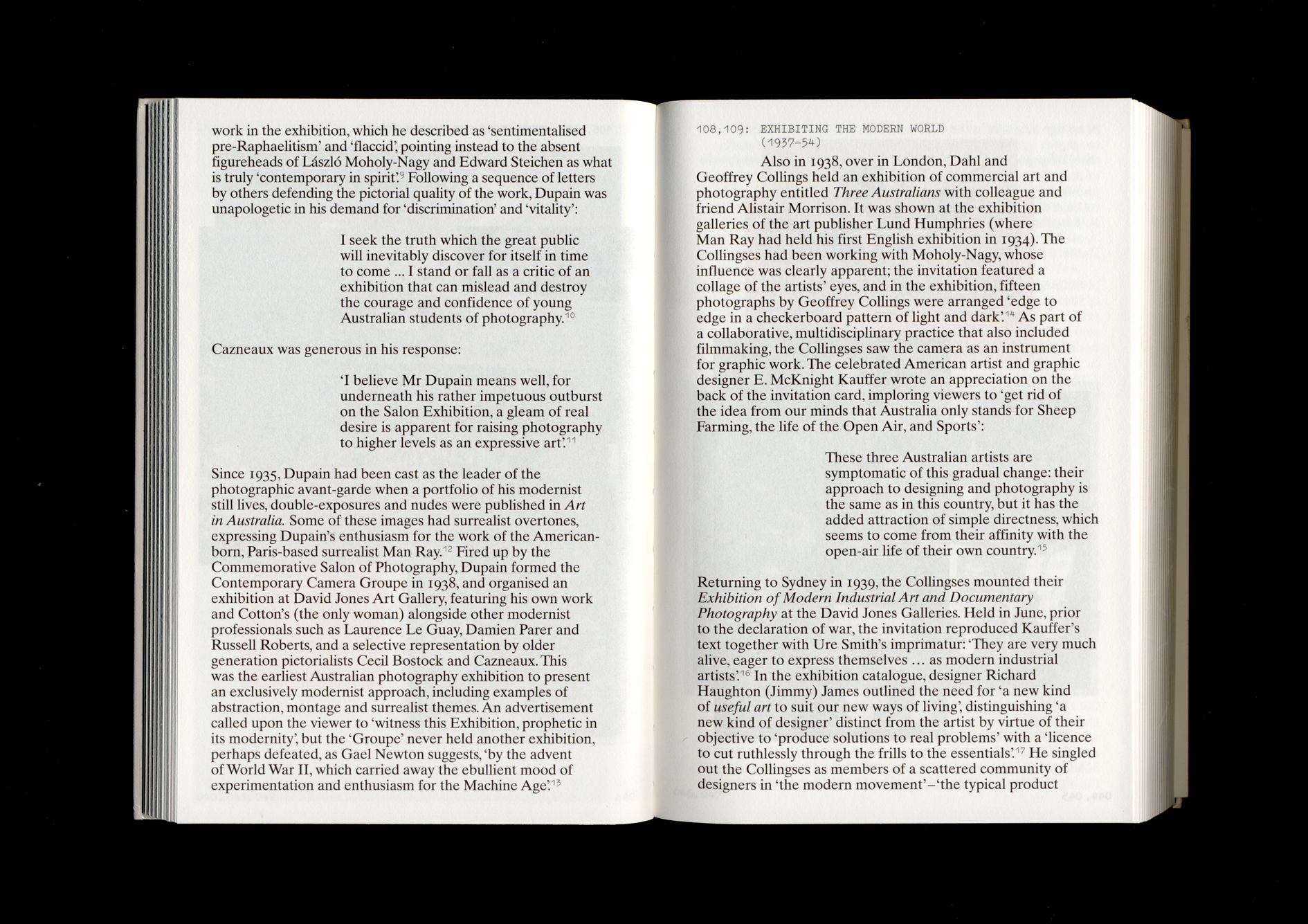

The show was housed in twin exhibition halls designed by prominent Melbourne architect Joseph Reed as provisional extensions to the Public Library (today’s State Library Victoria). Newspaper reports in Australia and abroad noted the grand dimensions of the spaces, their high walls and hemispheric ceilings.2 Images of the halls’ exposed timber rafters, wood-panelled roof and clerestory leadlight windows give the impression of a space halfway between a barn and a cathedral, a storehouse and shrine to colonial ‘progress’. Prismatic trophies of canned food in elaborate vitrines and taxidermy piled into glass cases occupied the central thoroughfare. These sat alongside an obelisk of orderly stacked macaroons (perhaps a gesture to the forthcoming 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris) and a curtained dome showcasing locally made pianos.

The exhibition’s catalogues classified photographs under the heading of ‘ornamental arts’, attributing them to individuals, studios and government agencies.3 They were listed alongside bookbinding, stationary, lithography and engraving, and clearly separated from the genre of ‘fine art’. If we were to judge solely from the partial and sometimes belated surveys of these catalogues, photography would appear to have played only a minor role in the exhibition. However, the Melbourne photographic studio T. Ellis & Co. had purchased exclusive rights to produce a portfolio of twenty-four views of the exhibition, in which we can see far more photographs on display than listed in the catalogue inventories, gesturing to their overall importance.4 Ellis & Co.’s view of the Great Hall shows photographs clustered along the side passages and pavilions. Single photographs, or multiple photographs collected into a single frame, were banked frame-to-frame on walls and colonnades. Photographs flanked the main halls, extending the field of vision of visitors from the displayed materials to the spaces of colonial modernity beyond the hall.

The Intercolonial Exhibition was a triumphalist representation of the colonial project. Indigenous weapons and tools were featured in state and regional pavilions, placed upon tables and arranged in such a way as to suggest how, beside examples of mechanised machinery and its outputs, they represented a lower level of ‘efficiency’.5 The photographs worked in unison with this narrative. The Great Hall included portraits of proud colonists and examples of Indigenous subjects, but the predominant subject matter for the camera was the ‘view’, particularly views of colonial ‘progress’. Redmond Barry, President of the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition council, commissioned hundreds of photographs of the Victorian boroughs and shires, believing that the medium provided ‘an unerring illustration of the conditions under which the towns of Victoria were springing into existence’.6 Barry’s request to government officials included a description of how the views were to be compiled, as fourteen uniform-sized, large-scale photographs of 10 x 12 inches (25 x 30 centimetres) mounted in one large frame with statistics showing the progression of each local district since 1862 placed in the centre. Views of cleared landscapes from other colonies also populated the walls, showing neat scenes of flourishing agriculture, the regulated curved contours of roads and landscapes stamped with structures of the colonial administration. In the Tasmanian section, William Cawston’s images of Launceston – including the government buildings on John Street, the Colonial Hospital (illustrated) and the Town Hall – were affixed to a piece of what looks like polished timber jutting out of the middle of a cascading mass of produce on the central table of the Tasmanian pavilion. These three images graphically visualised the prosperity which had also physically produced the products with which they were surrounded – goblets made from turned wood, a large hanging piece of animal skin and bottled wine.

Photographic views were such an important part of the Gesamtkunstwerk of the exhibition that, writing in the Australian Monthly Magazine, an anonymous ‘wanderer among the photographic views at the Intercolonial Exhibition’ commented:

The photographs of the exhibition are in themselves an interesting and instructive study. They mark the growth of art in this our antipodean world, and exhibit the high standard of taste to which we, as inhabitants of new colonies, have arrived. The degree of support it is obvious our photographic artists must receive is illustrative of our flourishing condition. In times of real scarcity of money, or depression of trade, those who subsist by the retailing of luxuries are the first to suffer. And is not photography a luxury? Undoubtedly it is, although so necessary to our enjoyment in this stage of the world’s advancement. The state of proficiency to which our colonial artists have arrived is a proof of their own ability and energy; and the daily increasing demand for that which assists us to admire the beauties of nature, and therein to learn more of the attributes and power of a Creator, is indicative of the degree of mental advancement to which we have attained.7

The reviewer, who called himself ‘Sol’ and displayed the technical knowledge of a professional photographer, dedicated his five-page report to discussing ‘Landscape Photography’, which he suggested ‘seldom calls forth in these colonies the powers of a critic’s pen, or attracts the attention of art worshippers’. He broke the bounty of images into three categories: stereographs, which included ‘instantaneous’ views of Melbourne and its suburbs by R. E. Josephs, ‘panoramic views, configured by joining separate photographs’ and ‘panoramic views taken on a wide-angle lens’.8 He praised Morton Allport’s stereographic views of Hobart Town, printed in collodio-albumen as glass transparencies, which visitors could view in a revolving stereoscope, commended H. A. Severn’s framed stereographs in the New South Wales Court, but noted ‘the effects of working out of doors, exposed to the hot winds and dust storms’ on some of them. Amidst the overall cacophony of the exhibition, the pseudonymous ‘Sol’ was very attuned to individual photographers displaying new technical and aesthetic developments. Thomas Foster Chuck, of Daylesford, showed some ‘excellent views of bush and rock scenery, exhibited in his own name in the Fine Art Gallery’. For these ‘happiest efforts’ Chuck made combination prints from more than one negative to deal with what the reviewer called ‘the presence of dead white skies’ produced by the orthochromatic emulsions of the time:

The light and shade are admirably managed, while the definition and detail are perfect, and exhibit careful manipulation and excellent printing The method by which a natural cloudy sky is made to take the place of the usual white background is worthy of consideration and practice, and in most instances is admirably managed.9

Scale was crucial to the impact of the photographs. Nearly all colonies were now using plates of up to 10 by 12 inches for their views. The panorama, although technically difficult (requiring the control of tonality across multiple images) was growing more and more in-demand, one five-frame panorama of Sydney from the North Shore even reached the size of 10 by 60 inches. The Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition consolidated the centrality of photography to Australian colonialism. Like the trophies that were placed in the centre of these exhibition spaces, it visualised and quantified colonial prosperity.

-

Intercolonial Exhibition, 1866: Official Catalogue, 2nd ed., Printed for the Commissioners by the Authority of Blundell & Ford, Melbourne, 1866. ↩

-

220 and 171 feet long and 82 and 25 feet wide, respectively (67 and 52 metres by 25 and 8 metres) each with 18 feet (5 metre) high walls. ‘The Intercolonial Exhibition – Progress of the Exhibition Building’, Australian News for Home Readers, 27 August 1866, pp. 8–11; ‘The Intercolonial Exhibition at Melbourne’, Illustrated London News, 2 March 1867, p. 215. ↩

-

See for example, Catalogue of contributions made by Tasmania to the Intercolonial Exhibition of Australia at Melbourne in 1866, James Barnard, Government Printer, Hobart Town, 1866; Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia, Melbourne 1866–67: official record containing introduction catalogues, reports and awards of the jurors and essays and statistics on the social and economic resources of the Australasian colonies, Published by authority of the Commissioners, Melbourne, 1867; Guide to the Intercolonial Exhibition of 1866, opened at Melbourne October 24, with preface by J.G. Knight, Melbourne, 1866. ↩

-

T. Ellis & Co., Australian Intercolonial Exhibition Photographs, Melbourne, 1866–1867, T. Ellis & Co., Melbourne, 24 album prints on card, 17.4 x 22.4 cm, in the collection of the National Library of Australia. ↩

-

Penelope Edwards, ‘“We think that this subject of the native races should be more thoroughly gone into at the forthcoming exhibition”: The 1866–67 Intercolonial Exhibition’, in Kate Darian-Smith et al (eds.). Seize the day: Exhibitions, Australia and the world, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2008. ↩

-

Redmond Barry, quoted in Paul Fox, ‘The Intercolonial Exhibition (1866): Representing the colony of Victoria’, History of Photography, vol. 23, no. 2, 1999, p. 174. ↩

-

Sol. (pseudonym), ‘A wanderer among the photographic views at the Intercolonial Exhibition’, Australian Monthly Magazine, no. 17, vol. III, January 1867, p. 360. ↩

-

ibid., p. 360. ↩

-

ibid., p. 364. ↩