(Installation View, pp. 203–214)

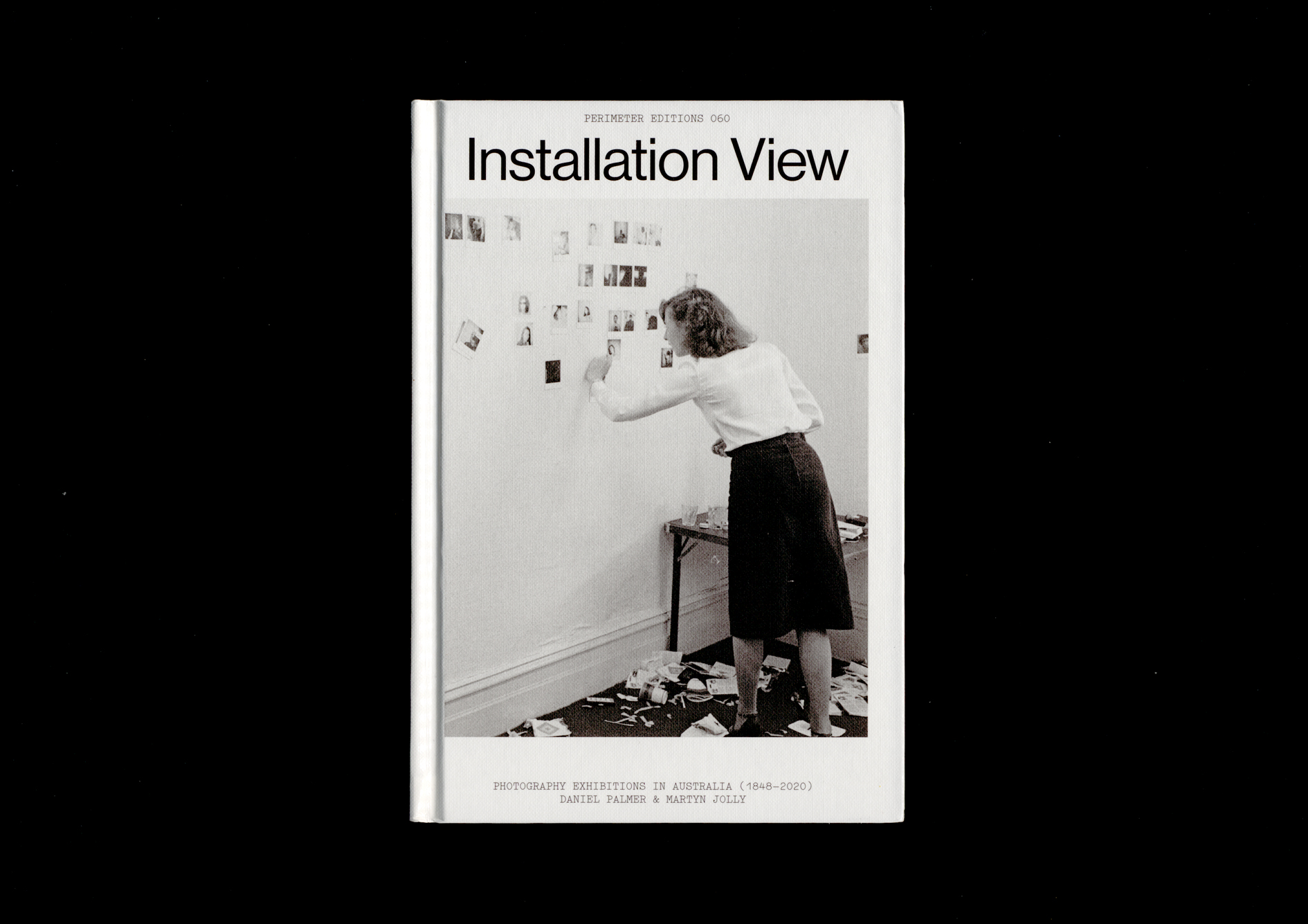

There were no women among the six photographers included in the Australian Centre for Photography’s (ACP) opening exhibition, Aspects of Australian Photography, in 1974. Nor were any women included in the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) first two major Australian photography exhibitions, The Perceptive Eye, 1969, and Frontiers, 1971. It is, then, all the more significant that in 1974 Sue Ford became the first Australian photographer to have a solo show at the new NGV at St Kilda Road, with Time Series, 1962–74 – the first of three she held there over her career.1 Rightly regarded as a key moment in Australian photography, Time Series comprises black and white double portraits of Ford’s friends and associates taken ten years apart and displayed side-by-side, producing a remarkable dialogue on the passage of time, identity and personal histories. In retrospect, the exhibition also marks a key moment in which a new feminist approach to photography became widely visible – an approach that, at the time, often focused on aspects of personal and domestic life, in keeping with the feminist slogan ‘the personal is political’.2

In 1971, Ford had held what is possibly the very first solo exhibition of photography by a woman in an Australia art gallery, at Hawthorn City Art Gallery. For this, her first exhibition, she showed two series of highly manipulated photographic works: the Suburban Series, 1962–71, comprising bleak images of suburbia and alienated individuals, including panoramas more than a metre wide; and The Tide Recedes, 1969–71, comprising large-format montage photographs that featured ‘superimposed images of nude figures with rock, water, seaweed, kelp and sand. The figures started out being recognisably human and finally metamorphosed into a sea animal’.3 As Helen Ennis has observed, ‘the large scale of the prints in The Tide Recedes indicated that they were conceived as art objects’.4 The Age titled its review ‘Photography as an art form’ and expressly pointed out that some photographers were shifting away from technical preoccupations to ‘artistic achievement’. Ford was celebrated as one of this new breed of creative photographers using the medium as ‘a means of expression’.5 As early as the 1960s, Ford had been a pioneer in developing what Ennis describes as ‘non-exploitative strategies [between photographer and subject] developed by feminist photographers a decade later’, referring to figures such as Carol Jerrems, Ponch Hawkes and Ruth Maddison.6 Along with Jerrems, Hawkes and Maddison, Ford was similarly interested in time and change, and her intimate photographs paid less regard to either the crafted, connoisseurial ‘fine print’ traditions or the tough, predatory ‘street photography’ traditions then underpinning the case for photography’s acceptance as art.

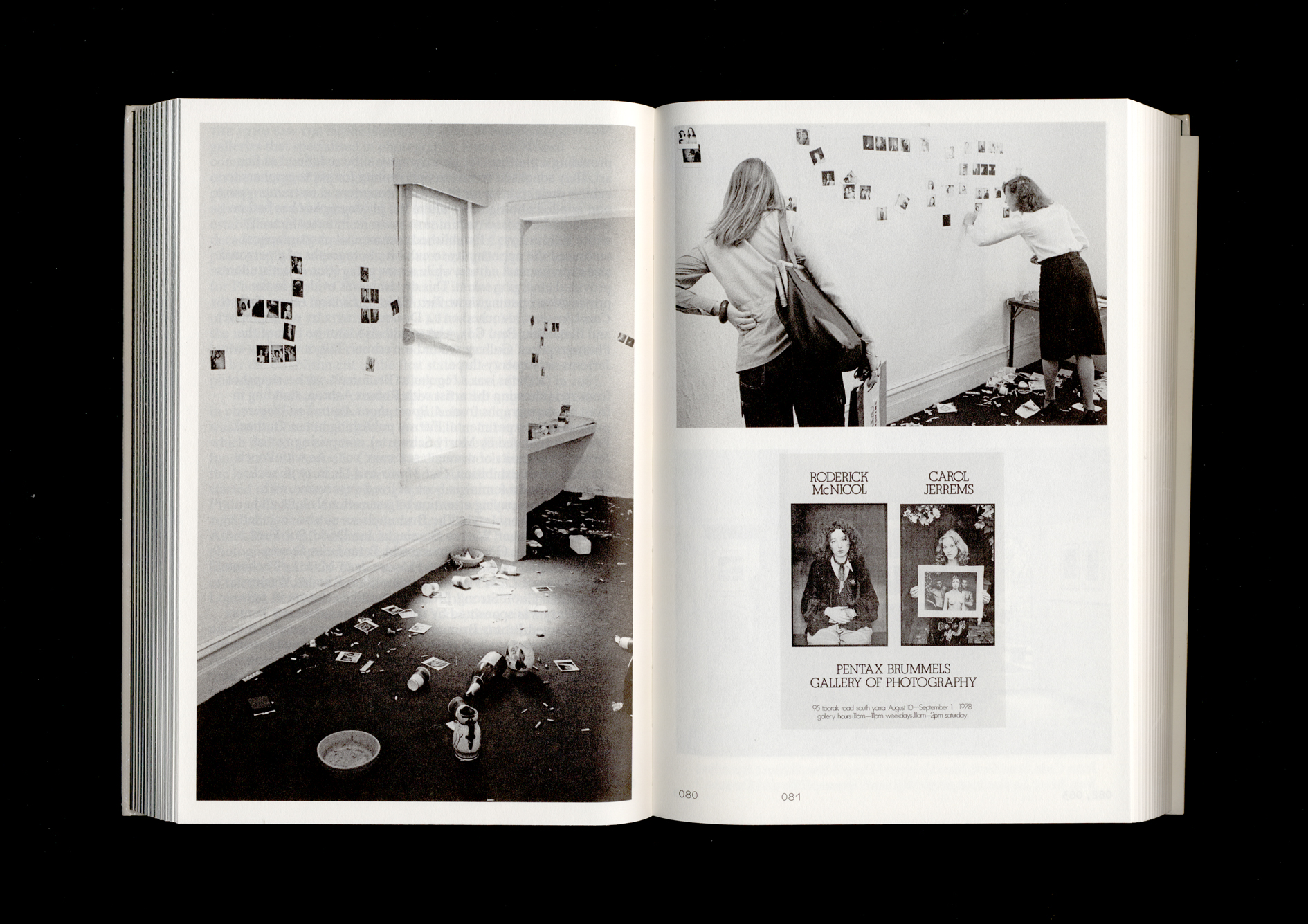

The times were changing. The Whitlam Labor government had come to power 1972, injecting money and energy into cultural production across the board. New galleries devoted to photography were emerging, especially in Melbourne. Carol Jerrems was a regular exhibitor at Brummels Gallery, and had her book of portraits, – A Book about Australian Women, published by Outback Press. As the authors of Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes note, the book was ‘a virtual exhibition’.7 Preoccupied by the lifestyles of subcultures and marginal groups, Jerrems found a way to infiltrate these communities and capture pockets of life previously ignored. The portraits featured portraits of women’s liberationists, Aboriginal spokeswomen, activists, students and dropouts, and were accompanied by text from Virginia Fraser. As with Ponch Hawkes’ first exhibition, Our Mums and Us at Brummels in 1976, Jerrems’ work reflected a feminism born of lived experience, with photographers paying attention to generational shifts and aspects of personal style.

1975 was International Women’s Year – with International Women’s Day in March generating energetic marches in capital cities – which gave new prominence and support to art and photography created by and for women. Sue Ford organised the exhibition Three Women Photographers: Micky Allan, Virginia Coventry, Sue Ford at the George Paton Gallery, University of Melbourne, where Allan’s handcoloured photographs Laurel,1975, were exhibited for the first time. But it was at The Pram Factory in Carlton, an alternative theatre and hotbed of feminist energy, where Allan, who had trained as a painter, held her first exhibition of photographs in 1974, and then began to handcolour them because ‘it seemed the obvious thing to do’.8 Allan had been working in set and poster design in the theatre when her friend Virginia Coventry – a minimalist painter – taught her how to process photographs in her darkroom. Later, in 1975, Jennie Boddington organised ‘Wimmin’: Six Australian Women Photographers at the NGV, with Fiona Hall, Marion Hardman (later Marion Marrison), Melanie Le Guay, Melanie Nunn, Jacqueline Mitelman, and Ingeborg Tyssen. In the same year, Boddington selected 150 photographs from over a thousand submitted for an exhibition and book titled Woman 1975, organised by the Young Women’s Christian Association of Australia. Funded by a federal government grant for International Women’s Year, Woman 1975 was positioned as both ‘historical record and social comment’ (like Jerrems’ book the previous year). However, the exhibition was far more mainstream, including a range of both male and female photographers – such as Hall, Tyssen, Le Guay, Mitelman and a young Sandy Edwards. Retaining echoes of The Family of Man, 1959, and Group M’s Urban Woman,1963, for Boddington the ‘overriding interest was in quality of image, nuance of expression, eloquent statement, no matter who the photographers might have been’.9 In a sign of how things have changed since, the cover image features a naked girl taken by a male photographer, Laurie Wilson.

The New York-based feminist art critic Lucy R. Lippard also visited Australia in 1975, and held a women’s-only talk at the Ewing and George Paton Galleries while in Melbourne. Stimulated by Lippard’s views, Lesley Dumbrell approached director Kiffy Rubbo with the idea of starting a feminist art group, and thus the Women’s Art Register was formed. In 1976, Suzanne Spunner, coordinator of the Melbourne Women’s Film Festival, called a meeting and LIP: A Journal of Women in the Visual Arts was launched. Published between 1976–84, LIP was written and designed by a collective of feminist artists, curators and critics. It foregrounded contemporary practice, reassessed the historically neglected, questioned boundaries between art and craft, and featured numerous articles on photography and the work of photographers including Virginia Coventry, Helen Grace, Ponch Hawkes, and Carolyn Lewens.10 Many in the LIP collective were closely involved with George Paton Gallery – including Judy Annear, Suzanne Davies and Denise Robinson – where photography by women became a core element of the program in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Micky Allan held her first major solo exhibition there, Photography, Drawing, Poetry – A Live-In Show in 1978, which included various photographic series such as portraits and My Trip, 1976, together with chalk drawings of gladioli flowers on brown paper, a range of domestic furniture incidentals such as photo postcards and plastic animals and, most notably, the artist-in-residence with whom visitors could interact. The exhibition blurred art and life, but went well beyond the merely diaristic and toured to Watters Gallery in Sydney. A 1979 photography installation by Ruth Maddison at George Paton Gallery focused on the overlooked rituals of everyday domestic life, also included furniture and flowers. Unusually, Allan produced further works from her solo exhibition by handcolouring the documentation photographs. Handcolouring was traditionally women’s work, and was fundamentally antagonistic to the prevailing purist, male-dominated black and white aesthetic of modernist photography. In 1979, Allan organised an entire exhibition, the Handcoloured Photo Show, at Tin Sheds in Sydney. Madison had taken up the practice, and it continued into the 1980s where it became a way for younger artists to engage with mass media and pop cultural imagery. In 1983, for example, Robyn Stacey exhibited Handcoloured Photographs at the George Paton Gallery.

Arguably one of the most important feminist exhibitions at George Paton Gallery was the historical survey Australian Women Photographers, 1890–1950 in 1981, organised by Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather with the help of Christine Gillespie. Based on extensive research, this exhibition featured more than a hundred photographs by twenty-four neglected female photographers such as Ruth Hollick and the Moore sisters, and travelled to nine venues over eighteen months, eventually becoming an extended book, Australian Women Photographers 1840–1960, published in 1986. Another notable feminist exhibition at George Paton Gallery was Helen Grace and Sandy Edwards’ Nothing New, Photography Etc. 1976–1981 in 1982. Grace and Edwards were members of the Sydney-based feminist collective Blatant Image (1979–82), which Grace formed around the Tin Sheds at Sydney University, prompted by her experiences with British feminist photography group the Hackney Flashers. Grace’s photographs of women at work were widely used in posters produced by trade union and women’s groups, and Blatant Image was also commissioned to produce a large photomural in New South Wales.

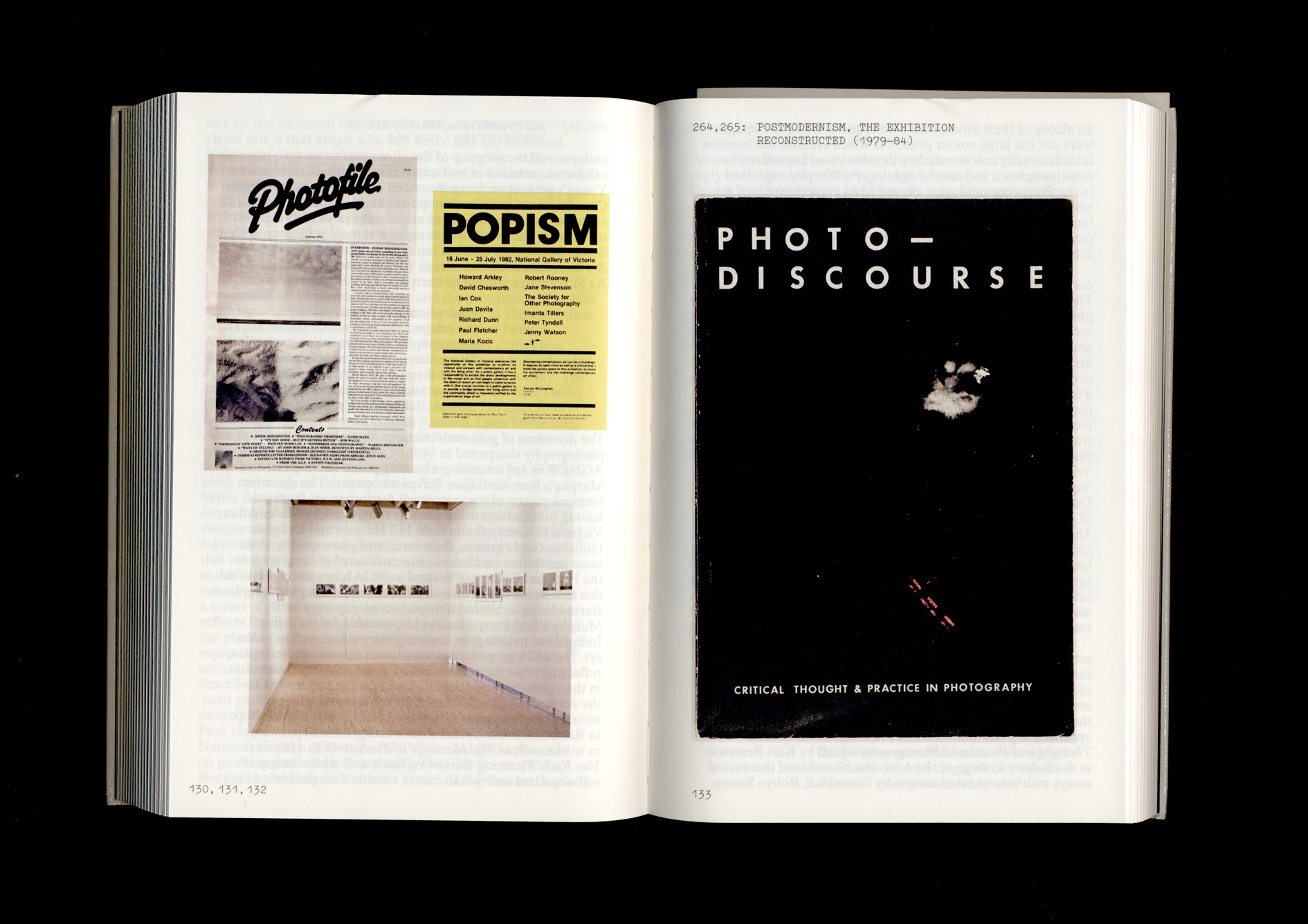

The influence of feminism became more complex in 1980s photography exhibitions. New shows were staged by a fresh wave of women emerging from art schools, most of whom were observers rather than participants in 1970s debates. It was increasingly apparent that feminist photography was not a single entity and included several strategies.11 Meanwhile, exhibitions of photography took on ever more ambitious forms in the postmodern 1980s. Significantly, the emerging trend of thematic group exhibitions at contemporary art centres now included photography as a matter of course. The new director of George Paton Gallery, Juliana Engberg, included a suite of Pat Brassington’s surrealist photo-collages in her 1987 group exhibition Feminist Narratives. Perhaps the most lasting proof of the legacy of feminist photographic practice from the 1970s is that the majority of the most celebrated photographers in the 1980s and 1990s associated with postmodernism were women, including Pat Brassington, Rosemary Laing, Tracey Moffatt, Julie Rrap and Anne Zahalka.

-

This exhibition is often cited as the first solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, but Mark Strizic had held a solo exhibition at the former State Library of Victoria site in 1968, a collection of portraits titled Some Australian Personalities. Strizic was also the first photographer to be acquired by the fledgling National Gallery of Australia, at the first acquisitions meeting in Melbourne in March 1973. ↩

-

Time Series toured to the Australian Centre for Photography, where it was reviewed by Daniel Thomas for the Sydney Morning Herald, who wrote that ‘their effect on the spectator is devastating … you will be disturbed by this reminder of your own mortality’. Daniel Thomas, ‘Nolan’s capacity for being astonished’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 July 1975, p. 7. Curators have recently held various survey exhibitions of feminist photography from the 1970s and 1980s. Kyla McFarlane curated A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art practice 1975–1985 at Monash University Museum of Art in 2011, and Shaune Lakin curated Photography Meets Feminism: Australian Women Photographers 1970s–80s at Monash Gallery of Art in 2014. ↩

-

Sue Ford, ‘The Tide Recedes’, in Professional Photography in Australia, September–October, 1971, pp. 31–4. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, ‘Past/Present’ in: Sue Ford: A Survey 1960–1995, exhibition catalogue, Monash University Gallery, Melbourne, 1995, p. 10. ↩

-

‘Photography as an art form’, The Age, Melbourne, 3 December 1971, p. 8. ↩

-

Ennis, ‘Past/Present’, 1995, p. 10. ↩

-

Joanna Mendelssohn, Alison Inglis, Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck, Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes, Thames and Hudson, Melbourne, 2018, p. 88. ↩

-

Micky Allan, ‘Without Fear or Favour’, in: Janine Burke, Helen Hughes (eds.), Kiffy Rubbo: Curating the 1970s, Scribe Publications, Melbourne, 2016, p. 108. ↩

-

See: Jennie Boddington, ‘Introduction’, Woman, Young Women’s Christian Association of Australia, East Melbourne, 1975, p. 7. ↩

-

The LIP collective included Judy Annear, Janine Burke, Isabel Davies, Suzanne Davies, Lesley Dumbrell, Elizabeth Gower, Christine Johnston, Lyndal Jones, Denise Robinson and Meredith Rogers. Suzanne Davies documented most of the George Paton exhibitions during the 1970s. See: Helen Vivian (ed.), When You Think About Art: The Ewing and George Paton Galleries, 1971–2008, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2008, p. 32. ↩

-

See: Catriona Moore, Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994. ↩