(Installation View, pp. 229–244)

To view one of the first ‘exhibitions’ of the history of Australian photography, you have to look in an unexpected place – the back of our first $10 note, designed by Gordon Andrews and in circulation from 1966, when Australia decimalised, until it was replaced by polymer notes in 1988. Printed in intaglio on the back of the note, behind a portrait of Henry Lawson, is a collage of photographs from the mining towns of Hill End and Gulgong. The source images for the collage were from the famous Holtermann Collection, acquired by the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, in 1952. That collection was the discovery of Vyvyan Curnow and Eric Keast Burke from the photography magazine the Australasian Photo-Review (AP-R). The covers of the AP-R usually featured portraits, landscapes or still lives by contemporary photographers, but the March 1953 issue featured an eighty-year-old photograph by Henry Beaufoy Merlin of a tailor’s shop on the goldfields of Hill End. The photograph and others like it had been discovered through the daughter-in-law and grandson of the wealthy nineteenth century gold miner Bernard Otto Holtermann, who were still alive and residing in Sydney at the time. In his breathless report to the AP-R, Keast Burke likened the discovery of what was to become known as the Holtermann Collection to the 1922 opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb: ‘Here, neatly stored in fitted cedar boxes were incredible numbers of negatives, records that were in due course to disclose every detail of the lives of our goldfields pioneers’.1

What was especially significant about the treasure Burke and Curnow discovered in that suburban shed was that it took the form of 3500 well-preserved negatives, not faded prints. Using modern darkrooms, Kodak duplicated and enlarged the negatives for exhibitions in the state libraries and Kodak Galleries of both Sydney and Melbourne, and in Hill End itself. The photographs were reproduced extensively in the press, all of which eventually led to the $10 note.

The Holtermann discovery was a critical moment in Australian photographic historiography, but not the only one. In 2007, for instance, another collection of nearly a thousand prints associated with Holtermann came to light and was acquired by the National Library of Australia.2 But, back in 1953 in the same year the Holtermann collection was being revealed, Sydney’s venerable Freeman portrait studios printed 355 of their carte de visite glass negatives originally taken between 1875 and 1880 as black-and-white display enlargements. After the exhibition, the prints and negatives were given to the Mitchell Library. A selection of the female portraits, with biographies, were also reproduced as ‘Portraits from the Past’ in The Australian Women’s Weekly.3 The Weekly called the portraits ‘enchanting’ and commented: ‘Apart from its great historical interest, the collection is an invaluable social document of a period. It will be a treasury of authentic detail for artists, writers, and researchers of this and future generations’. Subsequently the studio presented the rest of their negative collection to the Library, which now numbers more than one hundred thousand negatives.

In 1973, after extensive additional research, Keast Burke published a book on the Holtermann collection, Gold and Silver: An Album of Hill End and Gulgong Photographs from the Holtermann Collection.4 The book used extreme enlargement to zoom in on faces. The same technique was used by the historian Max Kelly who published two books based on negative archives: A Certain Sydney: 1900, about the plague in The Rocks, and Faces of the Street, about the houses demolished for the widening of William Street.5 Writing in Photofile in 1983, Kelly joined other contemporary historians in arguing for photographs as a new kind of historical document which objectively recorded things other forms of records could not – intimate, contingent, human things. He noted:

[I]n an endeavour to tune the reader’s eye, and to motivate his and her mind, I included enlarged details from a number of the original photographs … it has been these details, thus isolated, that readers have remembered best.6

By the mid-1970s, a sense of an Australian photographic history was also emerging at new photography collecting institutions such as the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). Likewise, the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) was engaging with history, mounting an exhibition in 1975 of new prints from a National Library of Australia collection of 900 negatives taken by Dr Charles Gabriel in Gundagai at the turn of the twentieth century; and in 1976 David Moore made sepia-toned prints from the negatives of Henri Mallard which had been gifted to the ACP (which toured as the exhibition Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge). The Max Dupain Retrospective 1930–1975, also at the ACP, included fresh prints from the same period, helping to make iconic his Sunbaker photograph from 1937 which had not previously been widely seen.

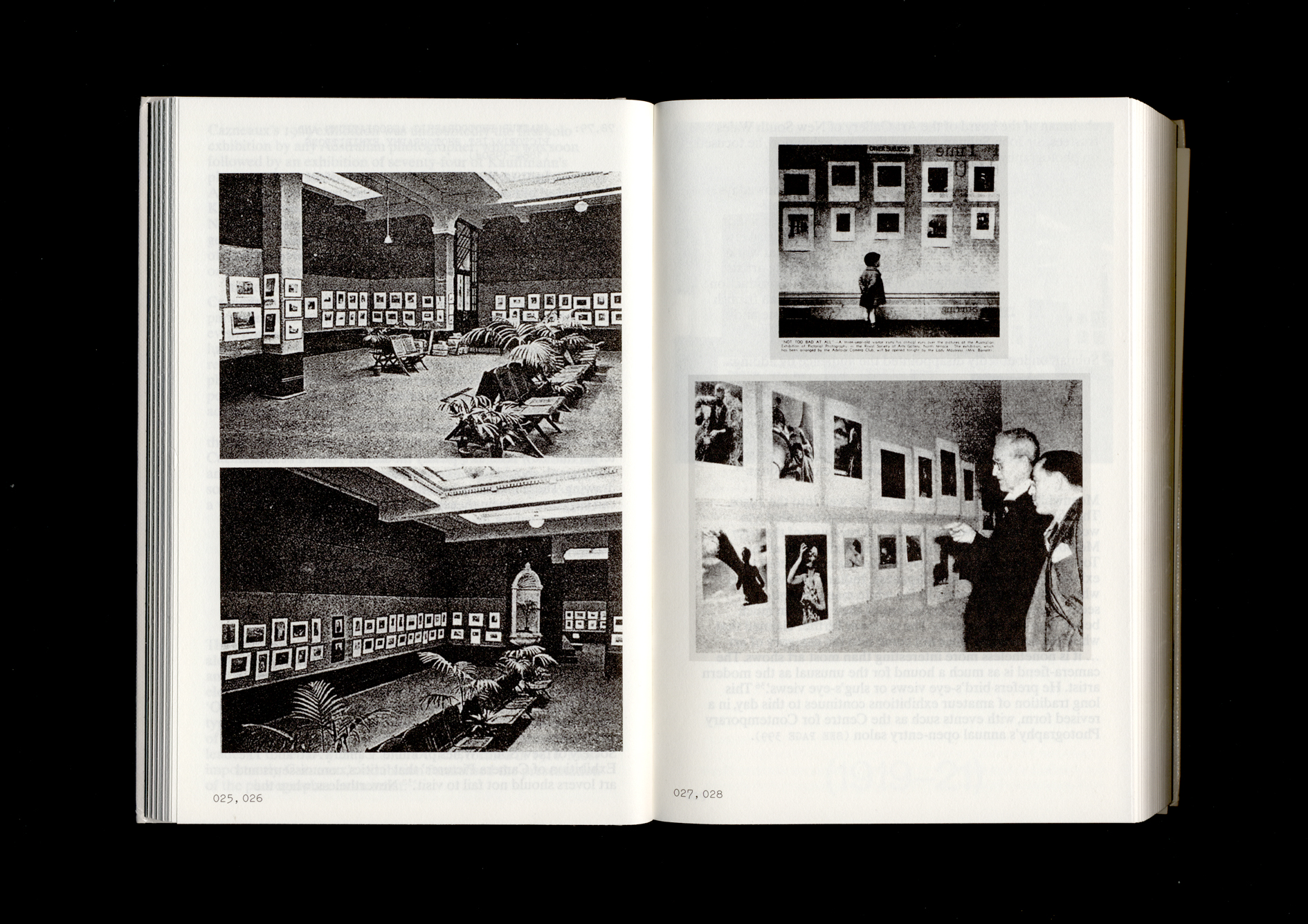

While historians and photographers were discovering photographs as sources of palpable historical information, other curators were forming an aesthetic history of Australian photography which was built on the sanctity of the vintage print. Gael Newton had been appointed inaugural curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) in 1974 and established links with the remaining pictorialist photographers in Sydney. In 1975, Harold Cazneaux’s daughters donated ninety of his photographs to AGNSW. This coincided with the gallery’s exhibition Project 7 – Harold Cazneaux: 1878 to 1953, curated by Gael Newton. The exhibition included vitrines displaying his Sydney Ure Smith publications as well as one of his cameras. Newton was invited to some of the last meetings of the Sydney Camera Circle in 1977, and curated an exhibition of Australian Pictorial Photography at the S. H. Erwin Galleries in 1979 (which later toured to China), and Silver and Grey: Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900–1950 at AGNSW in 1980 (which was also published as a hardcover book).

In 1976 Daniel Thomas, senior curator of Australian Art at AGNSW, included twenty-one photographs in the AGNSW exhibition Australian Art in the 1870s. The Australian Gallery Directors Council funded cultural theorist Anne-Marie Willis to research nineteenth century photography for a proposed exhibition, and funded the photographers and writers Barbara Hall, Jenni Mather and Christine Gillespie to embark on the Australian Women Photographers Research Project 1890–1950, generating a travelling exhibition at the George Paton Gallery in 1981. At the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), the curator of prints and drawings, Alison Carroll, began curating exhibitions of historical as well as contemporary photography in the late 1970s. Photographs collected in the 1920s started to be celebrated, and in 1981 Carroll curated a show on the Adelaide pictorialist Frederick A. Joyner (Real Visions: The life and work of F. A. Joyner, 1863–1945). Importantly, a few art and book dealers began to deal in historic Australian photography, reappraising colonial photography with an emphasis on collectable ‘vintage’ prints, most notably the Josef Lebovic Gallery in Sydney, which opened in 1977 and continues to this day. Lebovic deals in nineteenth- and twentieth-century photography as well as original prints and posters, and has also produced a series of authoritative catalogues accompanied by exhibitions of historical work, including Australian Photography 1850–1930 (1983), Charles Bayliss: Colonial Photographer (1984) and Masterpieces of Australian Photography (1989).

In short, the 1970s represented a period of broad engagement with the idea of an Australian photography, leading up to the bicentenary of 1988, which only intensified the interest, with the realisation that the rediscovery of Australia’s photographic past was closely entwined with the contemporary politics of representation and identity. The two books that were published on the history of Australian photography in 1988 took radically different approaches to the same material: Anne-Marie Willis’s Picturing Australia: A History of Photography was a ‘social history of photography’7 while Gael Newton’s Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988 ‘trace[d] the history of photography as an art in Australia’.8 Newton’s research was conducted at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) and resulted in a landmark exhibition.9 These books laid the template for a string of subsequent exhibitions at all the major galleries. They tended to included either canon-making monographic exhibitions on significant nineteenth- and twentieth-century figures, such as the NGV’s exhibitions on Athol Shmith in 1989 and Fred Kruger in 2012, or regionally based exhibitions such as Queensland Pictorialist Photography, at the Queensland Art Gallery in 1984 and A Century in Focus: South Australian Photography 1840s to 1940s, curated by Julie Robinson in 2007 at AGSA.

Thematic museum shows, such as Helen Ennis’s National Portrait Gallery exhibitions Mirror with a Memory, 2000, on portraiture, or Reveries: Photography and Mortality, 2007, on death, have been rarer but served to significantly deepen the conventional understandings of our photographic history. Portraits of Oceania, 1997, for instance, curated by Judy Annear at AGNSW, with a powerful essay by Brenda L. Croft, hung nineteenth century ‘anthropological’-style Indigenous portraits in austere but confronting grids.10 Such historical rethinks continued into the new century. The 2002 rehang of the colonial galleries at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia in Federation Square prominently featured Brook Andrew’s signature work Sexy and Dangerous, 1996, where a hundred-year-old Indigenous postcard portrait from the Charles Kerry Studio was enlarged and updated with contemporary slogans using digital printing technologies. The NGV bought two of an original edition of twenty to ensure it could keep it on permanent display, so ‘obsessed’ did it become with the work.11 The contemporary photograph’s disruption to the narrative offered by colonial paintings has now become a curatorial trope.

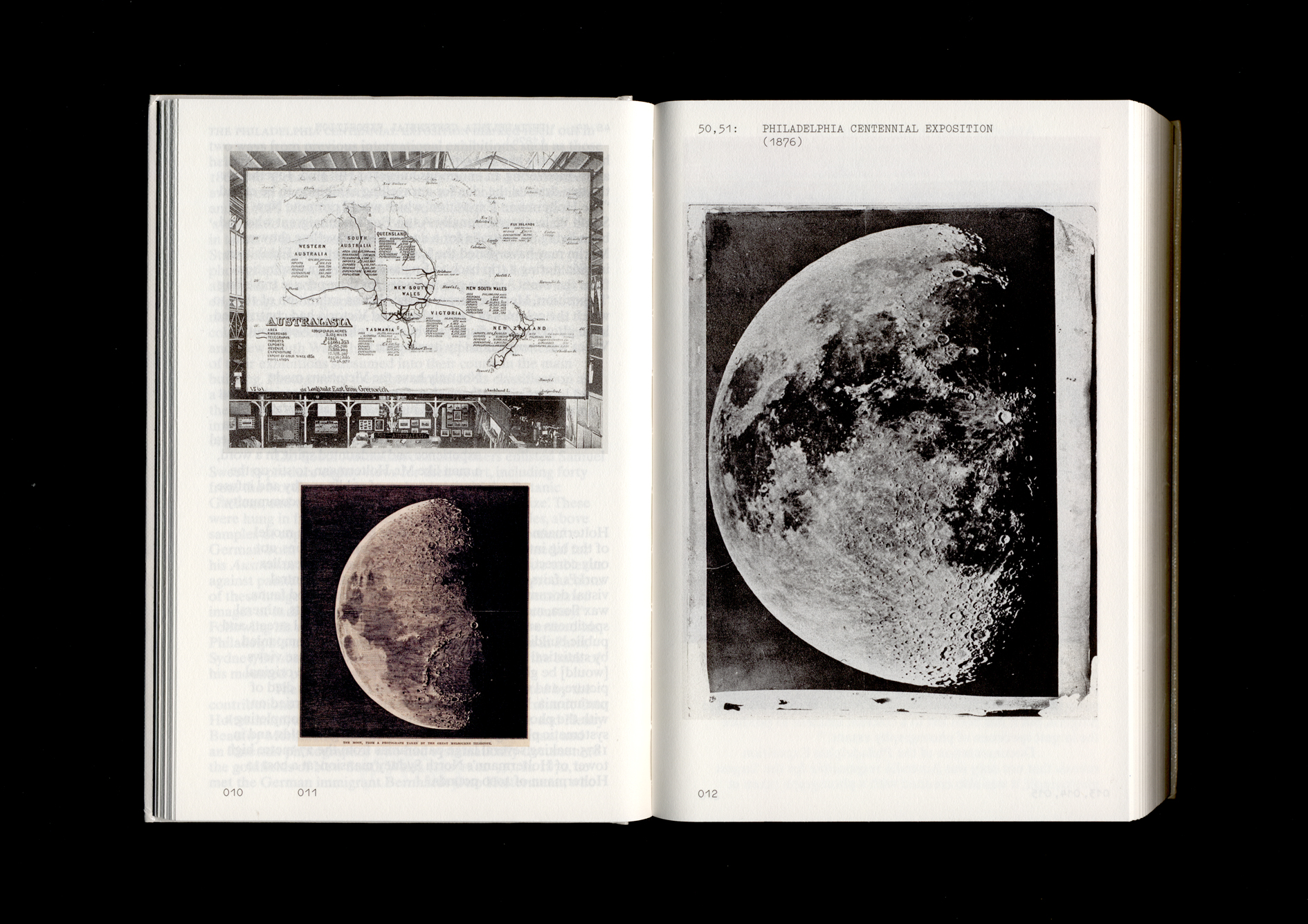

The NGA had been established with the prolific purchasing of the European and American canon. Under foundation curator Ian North, 800 new photographs were noted in the 1980–81 acquisition report.12 Prior to the gallery’s opening, a 1980 exhibition from the collection, Photography: The Last Ten Years, at Melville Hall at the Australian National University, presented Robert Besanko, Bill Henson, Carol Jerrems and Roger Scott among a roster of international stars. The first two photography shows after the gallery opened in 1982 were both historical surveys. Max Dupain launched International Photography 1920–1980 in the gallery’ s dedicated ground floor photography gallery. And later, upstairs in the education gallery, Pictorialism to Photojournalism surveyed Australian photography. Under a new director in the 2000s, the gallery shifted its focus from nationalistically defining an ‘Australian’ photography to placing Australian photography in a wider global context, resulting in the 2008 exhibition curated by Gael Newton, Picture Paradise: Asia-Pacific Photography 1840s–1940s. This exhibition put the old favourites of Australian photographic history in an Asian context. The gallery’s print of Holtermann’s giant panorama, first exhibited amongst the cacophony of produce in 1876, was especially framed and exhibited in dramatic isolation.

Other major survey exhibitions of Australian photography became dialogic rather than definitional. The Australian War Memorial began to include more personal and vernacular photographs in its exhibitions, and Judy Annear’s World Without End: Photography and the 20th Century, at AGNSW in 2000, exhibited Australian work alongside international photographs as objects in albums and books, rather than just as framed images. Annear’s ambitious exhibition, The Photograph and Australia, at AGNSW in 2015, foregrounded the material presence of the photograph as an object. A large number of Australia’s precious remaining stock of daguerreotypes were displayed nestled within their hand-sized cases, while mammoth collodion negatives from panoramas were placed on light boxes. Comprising hundreds of photographs – too many for one reviewer who complained of an avalanche of ‘minor works’ – it focused on the unseen riches of nineteenth-century photography.13 Much of the exhibition comprised photographs Annear had discovered in a wide variety of Australian archives, rather than gallery collections. The exhibition displaced what had previously been identified as key historical watersheds, such as international modernism in the 1930s or the photo boom of the 1970s, and through a thematic rather than chronological installation put historical photographers in dialogue with contemporary artists such as Anne Ferran and Sue Ford. The exhibition foregrounded photography’s longstanding ubiquity as a ‘mass’ medium: large quantities of cartes de visite portraits, the ‘social media’ of the nineteenth century, were displayed in a grid near a contemporary installation based on online image searches by artists Patrick Pound and Rowan McNaught.

-

Australasian Photo-Review, vol. 60, no.3, 1953, p. 140. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, A Modern Vision: Charles Bayliss, Photographer, 1850–1897, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2008. ↩

-

‘Portraits from the Past’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 16 September 1953, pp. 12–13. ↩

-

Eric Keast Burke, Gold and Silver: An Album of Hill End and Gulgong Photographs from the Holtermann Collection, William Heinemann, Melbourne, 1973. ↩

-

Max Kelly, A Certain Sydney: A Photographic Introduction to Hidden Sydney, 1900, Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1977; Max Kelly Faces of the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, Doak Press, Sydney, 1982. ↩

-

‘More to the Obvious Than Meets the Eye’, Photofile, Winter 1983, p. 10. ↩

-

Anne Marie Willis, Picturing Australia: A History of Photography, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1988. ↩

-

Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, Australian National Gallery, Canberra,1988. ↩

-

See: Geoffrey Batchen, Each Wild Idea: Photography, Writing, History, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2002, pp. 27–55. ↩

-

Brenda L. Croft, ‘Laying Ghosts to Rest’, in Judy Annear (ed.), Portraits of Oceania, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1997, pp. 5–14. ↩

-

Tony Ellwood quoted in Brook Turner, ‘Aboriginal artist and provocateur Brook Andrew on shaking up the Sydney Biennale’, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 October 2019. Online at: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/aboriginal-artist-and-provocateur-brook-andrew-on-shaking-up-the-sydney-biennale-20190930-p52w6c.html. Accessed 1 July 2020. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, ‘Split Mercury: Ian North’s Acquisitions for the National Gallery of Australia’, in Maria Zagala (ed.)., Ian North: Art/Work/Words, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2018, p. 159. ↩

-

The same reviewer also complained about having to peer into the glass cases in a darkened room (‘All viewers should be supplied with a flashlight and a magnifying glass.’). John McDonald, ‘Review: The Photograph and Australia exhibition lacks focus’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 April 2015. Online at: https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/review-the-photograph-and-australia-exhibition-lacks-focus-20150331-1mbnvl.html. Accessed 1 July 2020. ↩