(Installation View, pp. 61–66)

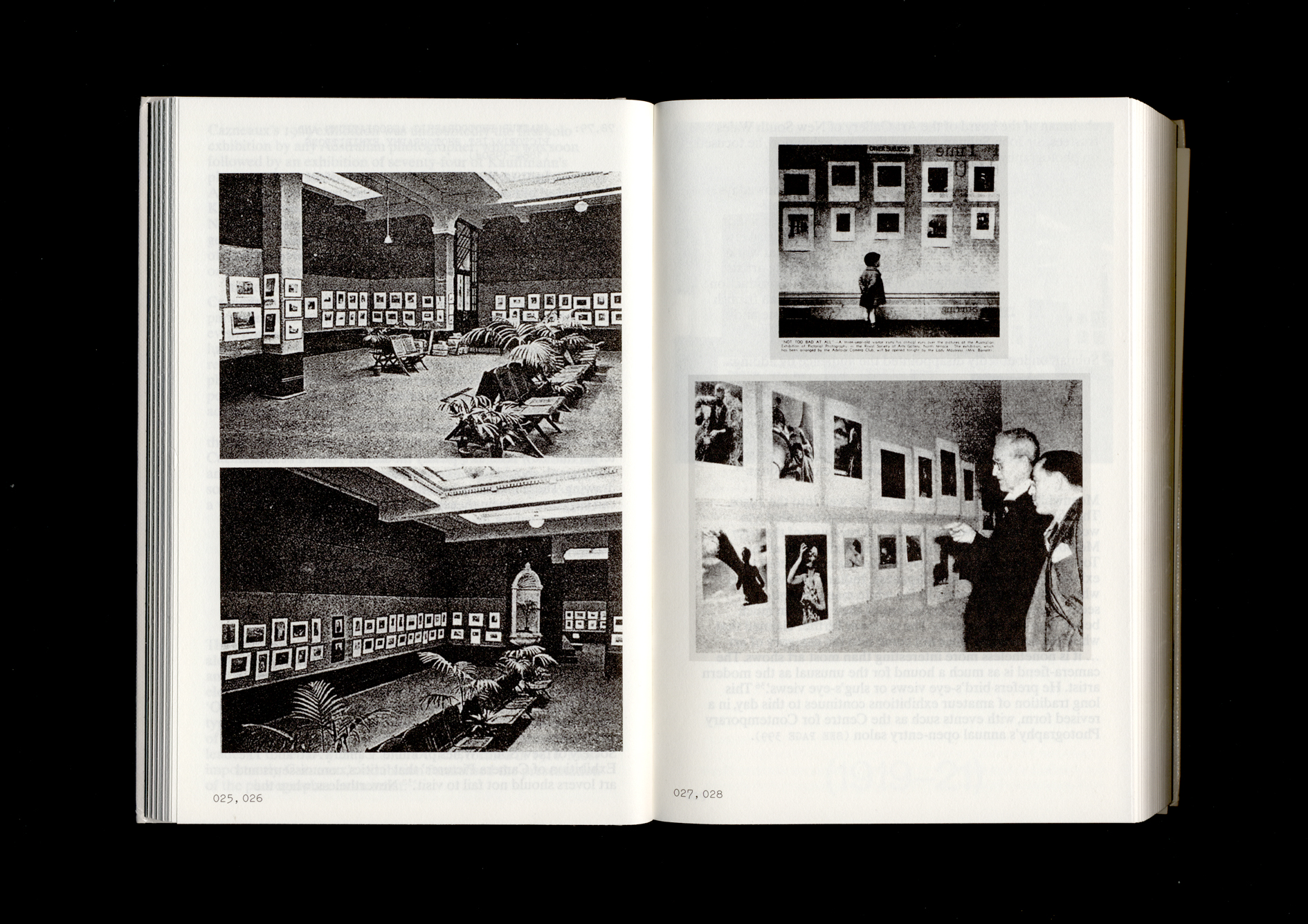

Eight years after the Royal Exhibition Building first opened for the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, it was occupied again for another exposition, this time the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition. The official photographers for the exhibition were J. W. Lindt and the exclusive portrait photography studio Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co., who each had their own court.

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co. converted their court into an ‘elegant saloon with voluminous draperies, mirrors, pot plants, and other ornaments, including a fountain in the centre’. Occupying the ‘place of honour on the wall’ were life-size enlarged portraits of the Governor of the colony and two eldest sons of the Prince of Wales, Albert Victor and George, who had visited Australia in 1880 with the Royal Navy.1

By contrast, Lindt decorated his pavilion with New Guinea fishing nets, spears, mats, implements and native ornaments, which surrounded photographs made in New Guinea on the Sir Peter Scratchley expedition of 1885. These solar enlargements, up to a size of 56 x 44 centimetres had already been shown at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in 1886, with a set presented to Queen Victoria. In Melbourne, they were contrasted with portraits of well-known Victorians enlarged to life-size.

International exhibitions always involved a judging process for the various displays, and the photography judges singled out the instantaneous wildlife photographs of the German inventor and photographer Ottomar Anschütz for their highest award. But they also praised Lindt’s New Guinea enlargements:

The photographs exhibited by J. W. Lindt, we find in every respect deserving a first award, with special mention for his ethnological photographs, landscapes, and photographs from shipboard; they are simply unique. From the technical point of view the mentioned pictures may be considered as the best in this Exhibition. The ethnological illustrations from New Guinea are even most interesting from a theoretical point of view. It has often been a matter of discussion how far, or whether at all, photography may be considered as a fine art. By the works of Mr. Lindt this question is decided in a way that is a triumph for his profession.2

Besides royalty and ethnography, another topic of growing popular interest amongst visitors to the exhibition was the giant trees of Victoria: just how big were they, and were they as large, or even bigger, than those in California?3 When the exhibition opened in August 1888 it was noted that there were no photographs of any giant trees, however towards the end of the run of the exhibition, giant tree photographs did appear. In January 1889, the photographer J. Duncan Pierce sent in ‘five fine photo enlargements of trees that are magnificent specimens of the products of the Australian forest’, which were placed on screens in the main hall of the exhibition building.4 The photographer N. J. Caire had also been finding giant trees in the mountains around Melbourne, and giving them pet names such as ‘Big Ben’ and ‘Uncle Sam’.5 They were hard to photograph in the impenetrable bush, but on 30 January 1889, in the final days of the exhibition, Caire displayed an enlargement of a ‘giant gum tree’ called ‘The Baron’ in the art gallery section of the exhibition, and his photograph was reproduced in the Australasian.6 He also bolstered his own display in the Victorian gallery with giant trees. ‘The Baron’ had a girth of 114 feet (35 metres) at the base and was optimistically estimated to be 466 feet (142 metres) tall. According to one newspaper, these ‘specimens altogether out-tower the former show of giant-tree photographs [of Pierce] exhibited by the commissioners in the main building’.7

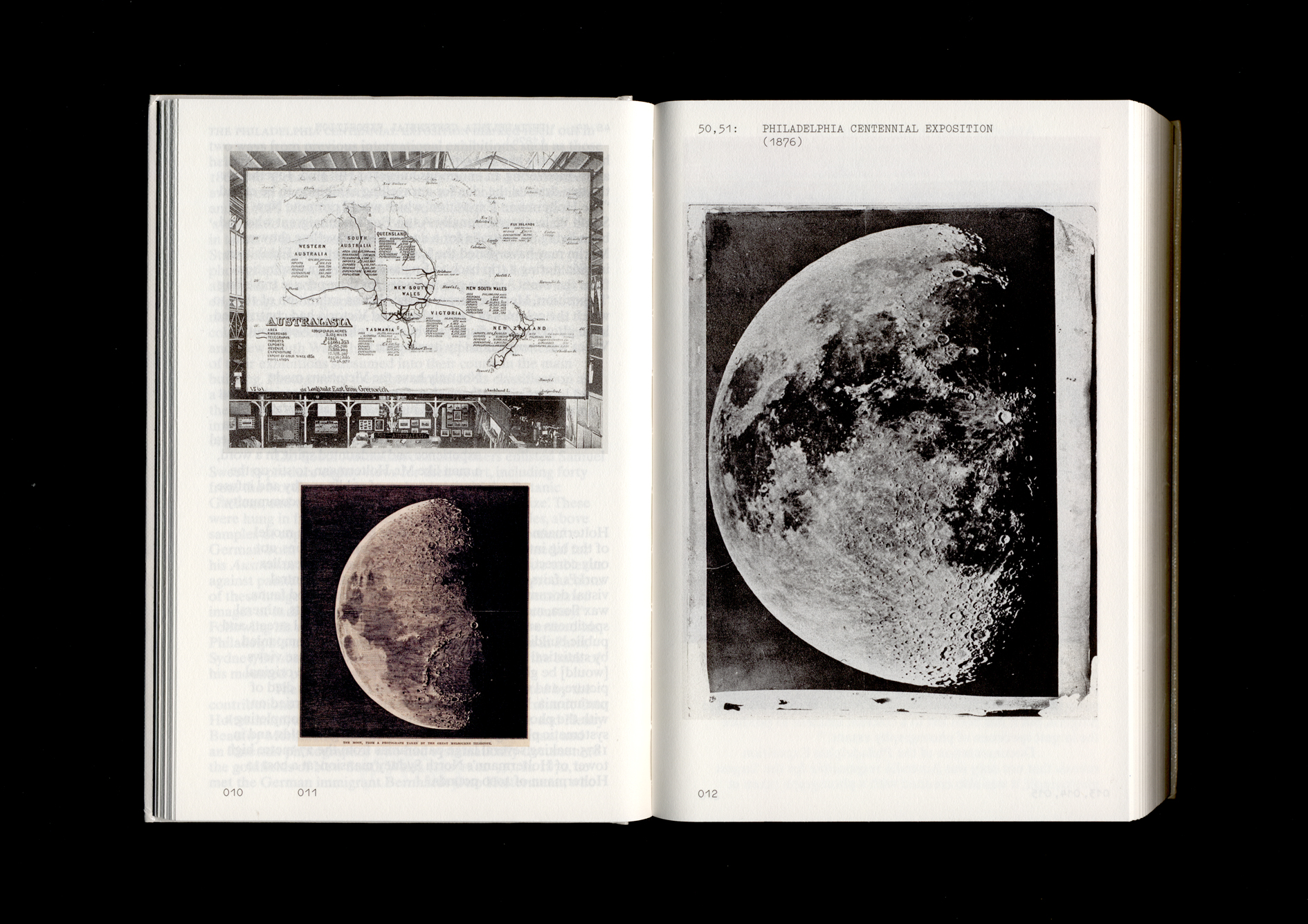

The Melbourne exhibition formed the basis for the Victorian contribution to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, the centenary event of the French Revolution for which the Eiffel Tower was built. The Australian colonies sublet part of the British Pavilion, where they showed familiar ‘trophies’ of produce, touted the benefits of irrigation, and sold Australian wine at cost price. In a remarkably detailed glass slide of the Victorian section of the Australian display, photographs by Caire and Pierce can be seen amongst plaster replica gold nuggets, stuffed kangaroos and specimens of natural history. Pierce’s giant tree enlargements, presumably similar to the ones displayed in Melbourne, are seen in frames, whereas Caire’s whole plate contact prints are pinned as a grid in a display cabinet. They are divided into two: half the display, ‘Melbourne’, is devoted to its brand new public buildings including the Royal Exhibition Building; the other half, ‘Bush Scenery’, is divided between natural beauty spots, including stands of trees and gullies of ferns, and several images of Aboriginal people from the Lake Tyers Mission, fishing from canoes and posing outside their humpies. In common with the majority of colonial representations, Indigenous Australians are positioned on the side of nature, in contrast to the new white settler culture.

-

The Australasian, 4 August 1888, p. 19. ↩

-

Official Record of the Centennial Exhibition, Melbourne, 1988–1889, Sands and McDougall 1890, Melbourne, p. 715. ↩

-

See Tim Bonyhady, Colonial Earth, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, pp. 191–218. ↩

-

The Week, Brisbane, 12 January 1889, p. 8. ↩

-

The Argus, Melbourne, 10 September 1888, p. 8. ↩

-

The Argus, Melbourne, 31 January 1889, p. 6; The Australasian, 16 February 1889, pp. 11–12. ↩

-

The Argus, Melbourne, 31 January 1889, p. 6. ↩