(Installation View, pp. 37–46)

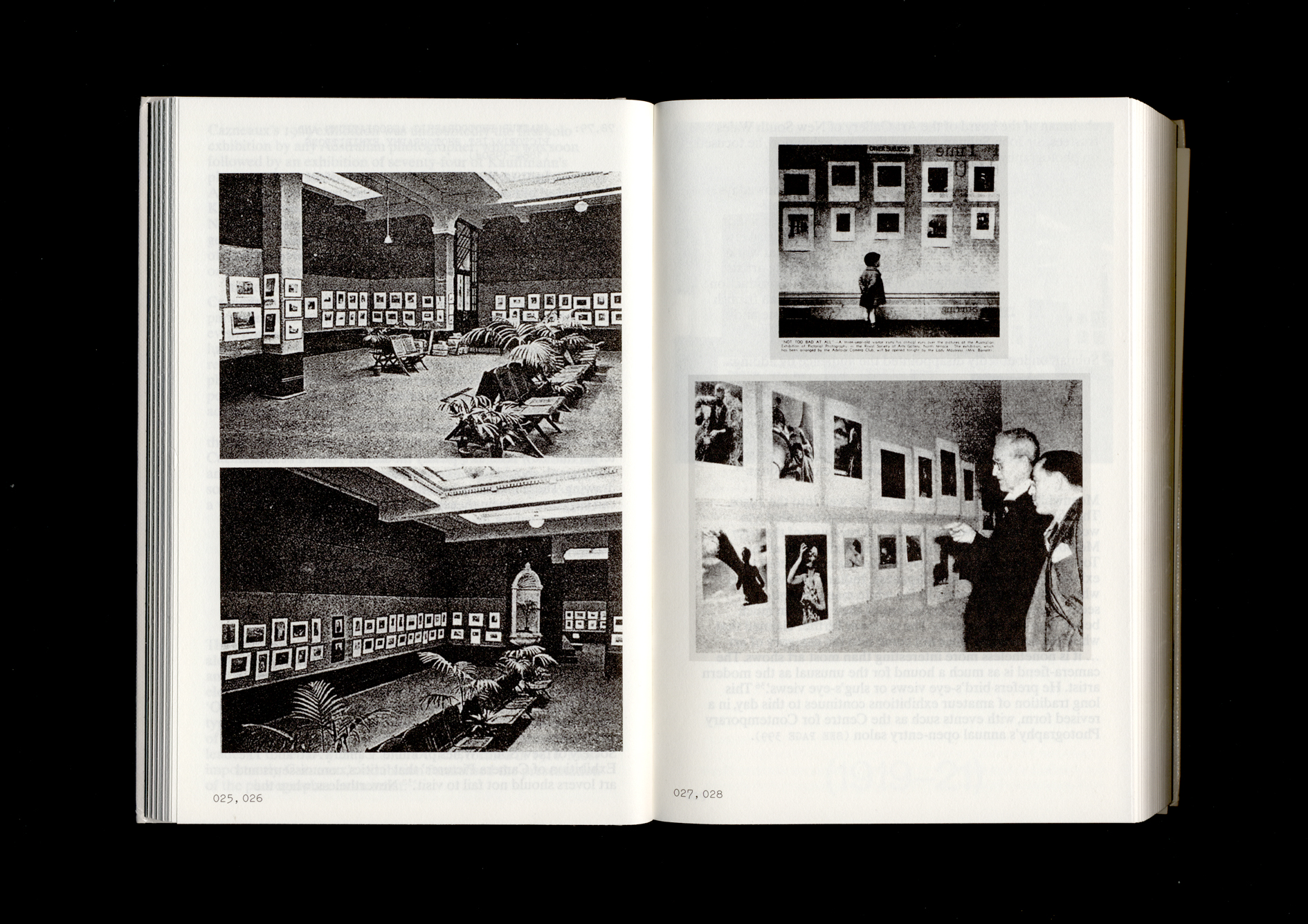

Designed to attract emigrants to Queensland rather than the rival colonies of Victoria and New South Wales, the entrance to the Queensland Annexe at the 1872 London International Exhibition was surrounded by polished samples of Queensland timbers, topped with a display of ‘native weapons’ flanked by two almost life-size, handpainted enlargements of ‘Queensland Natives’ taken by the Brisbane photographer Daniel Marquis.1 The facing wall featured fossils of prehistoric megafauna and a large map of the geology of Queensland, placed above glass cases containing arrangements of stuffed birds and animals. The floor was loaded with samples of cotton, coral, polished stone, gold nuggets and tins of preserved meat, all surrounding a bust of Queen Victoria, after whom the colony had been named. Tightly packed banks of brightly painted photographs, framed into uniform grids, were hung along the side walls. ‘The beautiful coloured photographs’, reported The Australasian Sketcher, ‘have always been amongst the greatest objects of interest. This is largely due to the novelty of the scenery and its vegetable products to English eyes, and the manner in which the characteristics of Australian landscapes are brought before them’. The grids were ‘arranged in geological sequence, beginning with the alluvial soils and ending with the volcanic’ and ‘[u]nderneath each photograph is a case containing the productions of the kind of soil represented above’.2

Most of the individual photographs, and the scientific approach to the design and installation of the annexe, were the work of Richard Daintree.3 Daintree had previously worked as an explorer, surveyor and geologist for the Victorian Geological Survey, and had produced the Colony of Victoria’s contribution to London’s International Exhibition of 1862. He then moved to North Queensland, where he became the government geologist and proposed to organise the colony’s contribution to the series of International Exhibitions planned for London from 1871 to 1874. In preparation, he made tours across Queensland before sailing for London in late 1870 with a large collection of specimens and glass negatives. In London, he found himself in the middle of a boom of spectacular new photographic technologies.4 Photography was entering what The Photographic Art Journal called ‘a new era’,5 when, ‘[n]ever were such facilities offered as now to the artist and amateur for the practice of photography’.6 These facilities, dispersed across different factories, retailers and studios, focused on the print, rather than the negative, and were not so much about capturing the image as reproducing and displaying it. They delivered four hitherto elusive qualities to photographs: large size, bright colour, automatic reproduction and guaranteed permanence. They included solar enlargers mounted into the wall or roof of a darkroom, projecting glass plate negatives onto albumen or carbon pigment paper. These could then be mounted on canvas or card, to be painted by colourists using specially manufactured oil paint, and framed in gold.7

At a cost to the Queensland taxpayer of three to four pounds per image, Daintree was able to make large grids of gilt framed, handpainted enlargements.8 Above each grid was a large sign describing each geological region, and below were table cases containing samples. The aim was to make the attractions of Queensland immediately legible for potential colonists, as their eyes vertically scanned down the different layers of signification – from the descriptive to the pictorial and the physical – and as their bodies moved horizontally through a virtual Queensland as represented by its geology. Not only was the display as a whole spatially systematised by geology, but the imagery within the spectacular grids of enlarged and painted photographs was also systematically classified by colonial occupation. Daintree’s geological photographs were taken deep within the landscape itself, however, the photographs he took specifically for the purpose of attracting emigrants took the form of stiffly posed tableaux comprising different types of colonial work that shared much with the dioramas used in imperial exhibitions since the Great Exhibition of 1851.9 Within the twin axes of their scientific and colonialist signification, the photographs seemed to encompass the ‘life’ of Queensland itself. As one visitor to the Queensland court of the 1873 Universal Exhibition in Vienna put it: ‘They are of high interest to the geologist, while at the same time the person who is not a geologist will be just as much interested’.10

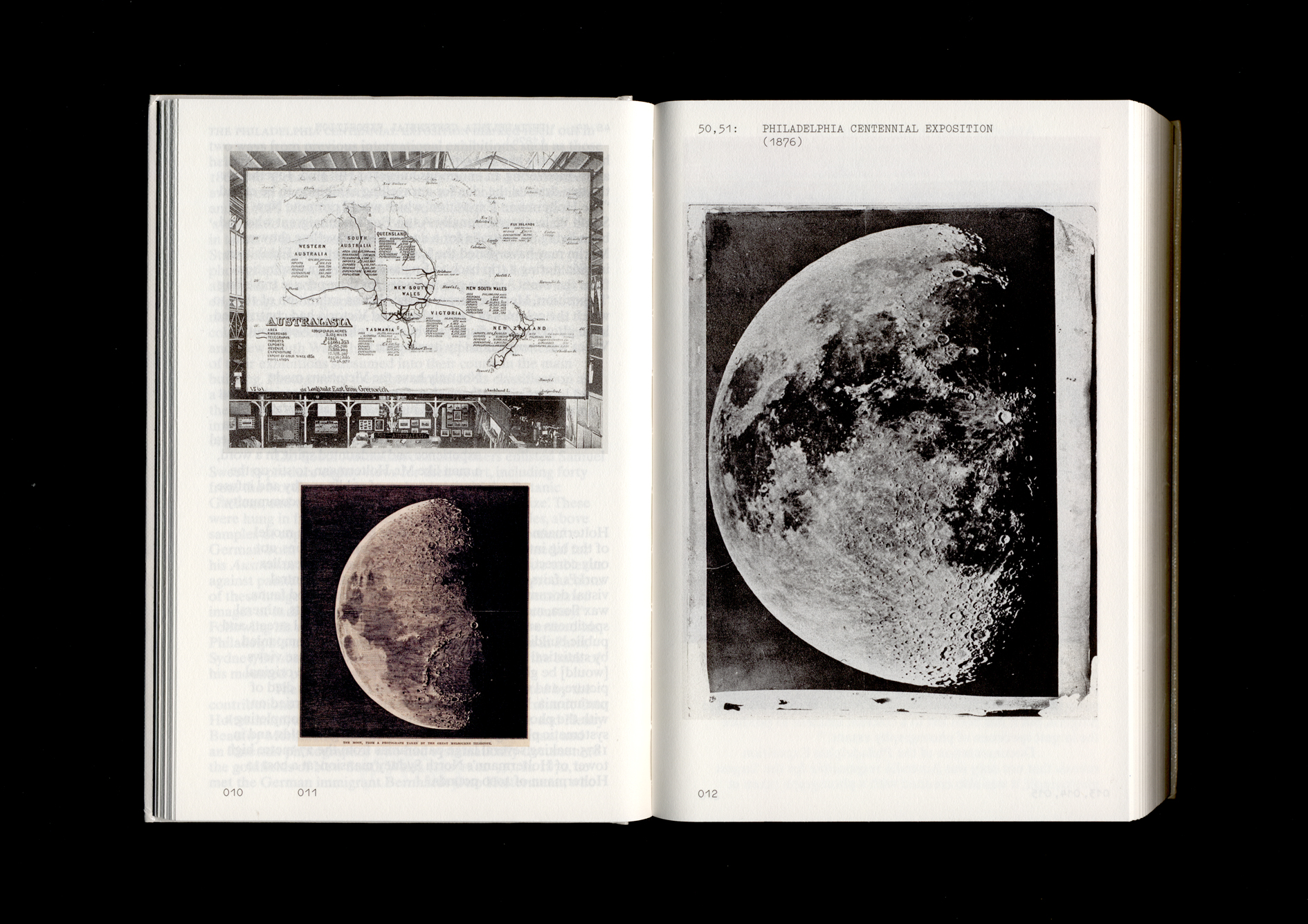

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia – the first official World’s Fair held in the US – with its large brightly lit spaces, offered Daintree a chance to elaborate his system. Looking at the stereographs of the installation of the Queensland Court by the Centennial Photographic Company, we can see 200 coloured photographs hung flush to the wall in gridded precision, echoing the geometric uniformity of the two tiers of clerestory windows that bathed the hall in even light. The Centennial Photographic Company’s stereographs of the Queensland Pavilion on the eve of its opening reveal two men loitering in the space, disrupting the labelled orderliness of the rock, wood and image displays. A woodcut was made from this photographic vision of controlled modernity and reproduced in the Australian Sketcher.11 A patriotic Queenslander in Philadelphia wrote for the Australian press that ‘it has been said several times that the pictorial section of the Queensland exhibit should have been in the art department, and as a collection, really deserved the honour’.12

Exhibitions of this period tended to be stratified into hierarchies: displays of raw material were lower than machinery or manufactured goods that demonstrated technical ingenuity, while the fine arts were usually quarantined from the applied arts. But to some visitors in Philadelphia, the sheer optical impact of what were now long, chromatically intense banks of brightly painted photographs, each in their own scalloped gilt frame, were beginning to exceed those established divisions. One enthusiast wrote:

I have entered the department … day after day, and am not yet tired of looking. The long, high walls are clothed with pictures – beautiful photographs colored to represent nature, as seen under the glowing sunlight of Northern Australia. The pictures are delightfully life-like, and as delightfully arranged. … It has been said several times here that the picture section of the Queensland exhibits should have been in the art department, and, as a collection, they really deserve the honor.13

In 1879, Daintree’s painted photographs were displayed in Australia for the first time as the centrepiece to the Queensland Court of the Sydney International Exhibition. However, in those long halls – much more elaborate than the small annexe that had been used in South Kensington seven years before – the two hundred or more painted photographs were no longer arranged in geological divisions. Instead, as a photograph of the exhibition taken by the New South Wales Government Printer reveals, they were arranged in long panoramic rows, rising in the centre of the display from between the glass cases, and curving over the visitor. Each chromatic field was topped with a sign announcing: ‘The Daintree Collection’. In short, Daintree’s authorship of images – exposed on the frontier, enlarged in the metropole, and spectacularly gridded together in the new spaces of the international exhibition – was now more pronounced than ever.

-

Michael Aird, ‘Aboriginal people and Four early Brisbane Photographers’, in Jane Lydon (ed.) Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2014, p. 149. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

For biographical information on Daintree see: Catherine Webb, Aspects of Place: The Queensland Images of Colonial Photographer Richard Daintree, unpublished thesis, Australian National University, 2018; Jenny Carew, ‘Richard Daintree: Photographs as History’, History of Photography, vol. 23, no. 2, 1999, pp. 157–62; G. C. Bolton, Richard Daintree, A Photographic Memoir, Jacaranda Press in association with the Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1965; Dianne Riley and Jenny Carew, Sun Pictures of Victoria: the Fauchery Daintree Collection 1858, Currey O’Neill Ross, Melbourne, 1983. Richard Quartermaine, ‘International Exhibitions and Emigration: the Photographic Enterprise of Richard Daintree, Agent General for Queensland 1872–76’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 7, no. 13, 1983, pp. 40–55. A large collection of Daintree’s Queensland photographs are in the Queensland Museum; significant collections are in the State Library of Queensland, Queensland Art Gallery, National Library of Australia, and National Museum of Australia; and an extremely important but neglected collection of glass plates is in the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. His Victorian photographs are largely in the State Library of Victoria. ↩

-

Although there was a shipwreck en route most specimens and negatives eventually survived. ↩

-

The Photographic Art Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, March 1870, n.p., and The Photographic Art Journal, vol.1, no. 2, April 1870, p. 18. ↩

-

The Photographic Art Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, March 1870, p. 8. ↩

-

ibid., p. 7. ↩

-

Quartermaine, ‘International Exhibitions and Emigration’, p. 49 ↩

-

See the 1855 photograph from the rebuilt Crystal Palace by Henry Philip Delamotte of ‘Stuffed Animals and Ethnographic Figures’ in Photographic Views of the Progress of the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, vol. II, London, 1855, plate 100. ↩

-

Australasian Supplement, 2 August 1873. ↩

-

‘The Queensland Court at the Philadelphia Exhibition: Evening before Opening Day’, The Australian Sketcher, 6 August 1876, p. 76. ↩

-

‘A Queenslander in America – VIII: At the Exhibition’, The Queenslander, 29 July 1876, p. 21. ↩

-

The Queenslander, 29 July 1876, p. 21. ↩