(Installation view, pp. 285–300)

On Australia Day 1972, four Indigenous men protesting against the government’s refusal to grant land rights established an Aboriginal Tent Embassy outside Parliament House in Canberra. The embassy is still there to this day. In 1981, a group of concerned Sydney artists formed the group Apmira: Artists for Aboriginal Land Rights to raise money for Aboriginal Land Councils through exhibitions and concerts (apmira is the Arunta word for ‘land’). In 1982, the year in which there were vociferous land rights protests at the Brisbane Commonwealth Games, the program included a concert, an exhibition of works on paper at Paddington Town Hall, and a photographic exhibition, After the Tent Embassy: Images of Aboriginal History In Black and White Photographs, at the Bondi Pavilion. The 114 photographs by twenty-nine photographers were researched and curated by Narelle Perroux and Wesley Stacey, one of the founders of the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) who had become involved with Indigenous culture while living on the South Coast of New South Wales. Perroux and Stacey powerfully juxtaposed copies of nineteenth century anthropological photographs and early twentieth century mission photographs sourced from libraries and government agencies against contemporary images of Indigenous life and political protests found in newspaper files and from non-Indigenous photographers such as Michael Gallagher, the English photojournalist Penny Tweedie (who had a concurrent solo exhibition at the ACP), and the activist photographer Juno Gemes (who had a concurrent solo exhibition at the Hogarth Galleries). All of these artists were committed to working within Indigenous communities.

The following year, the activist Marcia Langton edited a book based on the exhibition and wrote a passionate text that ran in short staccato bites beneath the photographs. In that same year, the exhibition toured to Canberra and was shown at the Woden Shopping Centre. During what was then called National Aborigines Day Observance Committee (NADOC) Week, it was shown at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and it is now preserved in that collection. As Catherine De Lorenzo notes, the ‘low budget exhibition included copies of prints of sullen colonial subjects, alongside vibrant images of activists for land rights and self-determination. Langton’s hard-hitting text running under the images was designed to leave no viewer wondering about the point of the exhibition’.1

Although After the Tent Embassy was the product of non-Indigenous photographers, an Indigenous photography revolution was afoot, driven by two factors: the increasing opportunities for education in photography through TAFE and tertiary courses, and the increased interest in Australian history and identity in the lead-up to the 1988 Australian Bicentenary. For instance, in the same year as After the Tent Embassy, Exiles, a small gallery in Darlinghurst, Sydney, held ‘the first ever exhibition by all Aboriginal photographers’, which was facilitated by Bruce Hart, who taught photography courses for young Kooris at the Tin Sheds Art Workshop in the University of Sydney.2 Later in the decade, the Indigenous press photographer Mervyn Bishop collaborated with the English cultural worker Andrew Dewdney, who had come from a background of cultural activism at the Cockpit Arts Workshop in London, on a course for students at the Tranby Aboriginal College called ‘Race Representation and Photography’ which resulted in an exhibition at the Tin Sheds in 19893.

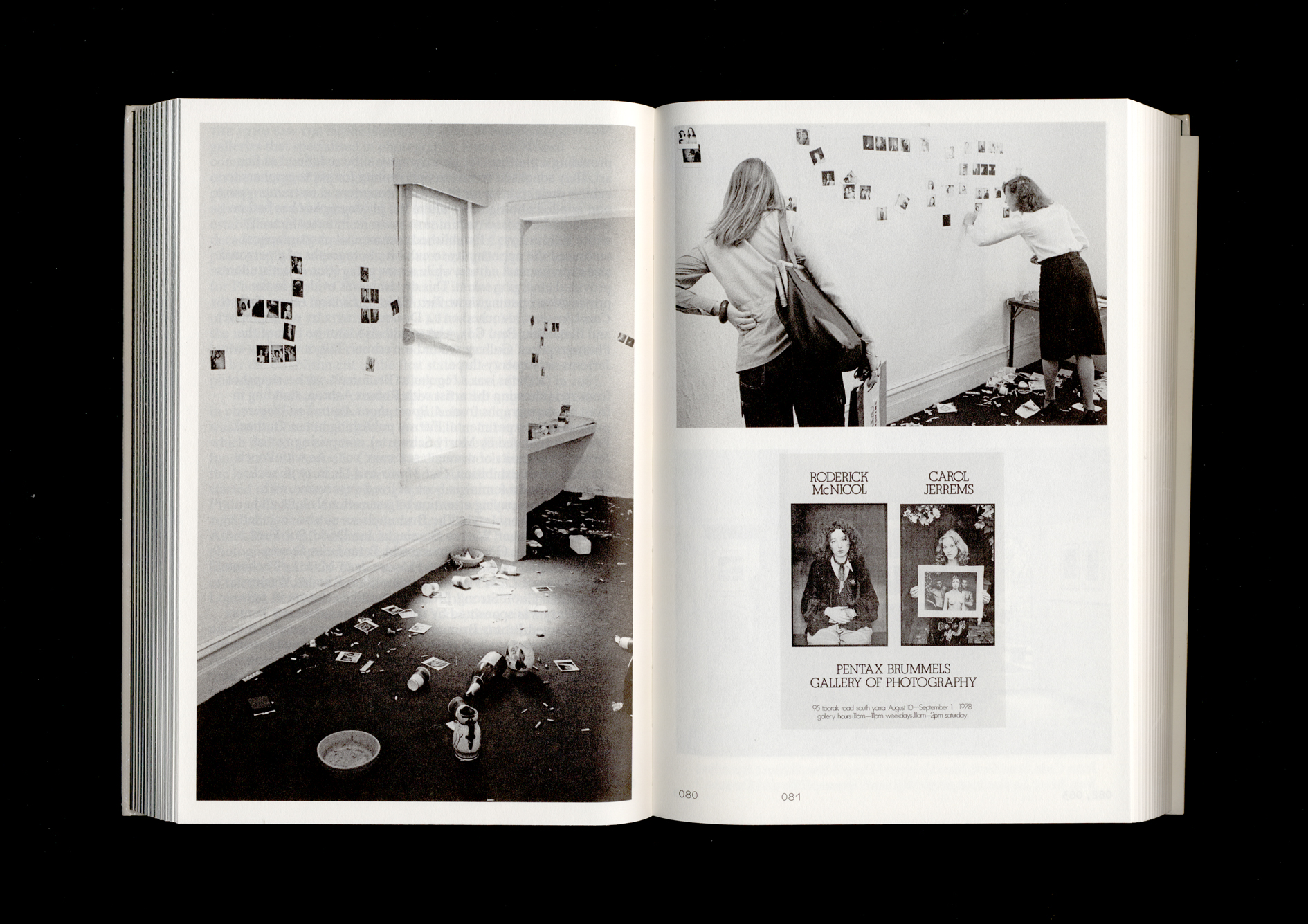

Meanwhile, the wider art world was being transformed by Indigenous photography. In 1983, the arts adviser Djon Mundine and curator Bernice Murphy brought bark paintings by David Malangi, along with works by other traditional artists, from the remote Arnhem Land Aboriginal community of Ramingining to the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) for the biennial survey of Australian art, Perspecta. In Ramingining, they also gave one of David Malangi’s sons, the painter Jimmy Barnabu, an Instamatic camera and a Walkman cassette tape recorder, inviting him ‘to produce any record desired of daily life and activities in this area’. Their purpose was ‘to seek a statement, using technological and electronic media, that would be an expression from ‘within’ Aboriginal culture, in contrast to similar photographic or auditory records that have been made in some senses from ‘outside’ the culture.4 The thirty-three small prints that resulted were displayed in a row along the wall, along with the audio. As Gordon Bull has reflected, ‘Barnabu’s work did not seem out of place in the exhibition’, about a quarter of which comprised photography or related media.5 In fact, Barnabu’s installation was not unlike the ‘conceptual’ installation Instamatic prints in Wesley Stacey’s The Road, 1975, or The Society for Other Photography’s conceptual installation of Polaroid SX-70 snapshots also included in the 1983 Perspecta.

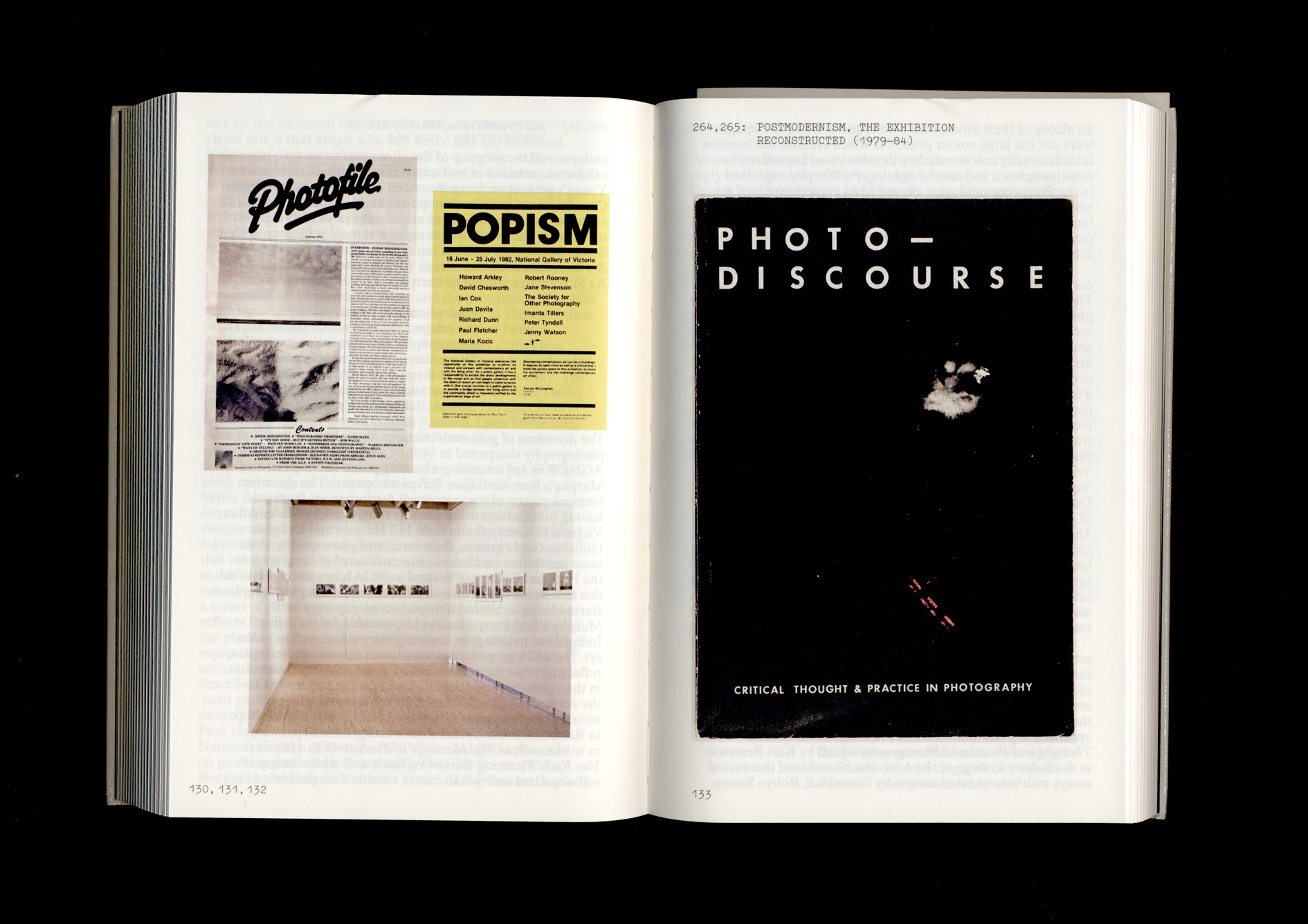

The following year Sydney’s Artspace held Koori Art 84, curated by Vivien Johnson, which featured the work of traditional and urban Aboriginal artists, including the urban Aboriginal photographers Michael Riley, Fiona Foley and Terry Shewring. Finally, two years later, during NADOC week, Sydney’s Aboriginal Artists Gallery held the National Aboriginal and Islander Photographers Exhibition, bringing together ten photographers, including Mervyn Bishop, Brenda L. Croft, Tracey Moffatt and Michael Riley. The gallery’s owner, Ace Bourke, told the Sydney Morning Herald: ‘It’s an exciting period for young Aboriginal artists. In photography, as well as in other fields, Aboriginals are emerging professionally’.6 The exhibition had been primarily organised by the young artist Tracey Moffatt, who told Photofile:

To be honest, we got the kind of publicity that makes me want to vomit; e.g. ‘they’re Aborigines, they’re articulate, and gee whizz, they take good pictures’ sort of stuff. I guess I shouldn’t complain because we did have a lot of people coming through looking at the show and buying work, which is what we do like!7

Two years later, to coincide with the 1988 opening of the new Parliament House, the Aboriginal activist, artist and writer Kevin Gilbert organised the group exhibition Inside Black Australia: Aboriginal Photographers nearby at Canberra’s Albert Hall. In the catalogue Gilbert declared:

At the material level we have been limited in our travel to localities by lack of money and facilities. Once again white Australia has been able to evade a net of factual proof in images that make Australia comparable with white South Africa’s inhumanity and apartheid and as deserving of worldwide condemnation.8

These exhibitions of Indigenous photography included a mixture of portraits, records of daily life and documents of political protests. Brenda L. Croft was included in both exhibitions, and commented at the time:

I became really aware how strongly I felt about Aboriginal people documenting Aboriginal happenings. I get angry when I see non-Aboriginal people doing it. … The people who really irritate me are those whose names keep constantly cropping up in every piece of documentation of Kooris, I feel like they’re parasites. It’s just another step on from the ethnographic or anthropological kind of thing. We can do it ourselves and that’s why I feel it is really important and why I’ve been tied up in all sorts of different things like media, photography, TV and that because it all sort of weaves in and out of each other, telling our own stories. That’s what was good with Inside Black Australia in that, OK, some people weren’t technically proficient but that didn’t stop them, it’s their viewpoint, it’s our viewpoint from the inside.9

Later Croft added: ‘I wanted to collaborate with people I knew, and, for me, it was really important that there was a relationship with the people I was photographing’.10

Photographers and subjects had to form relationships quickly for the After 200 Years project when, between 1985 and 1988, thirteen non-Indigenous and eight Indigenous photographers were sent to nineteen Indigenous communities. The project, coordinated by Penny Taylor for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, hoped to move into the ‘everyday world of Aboriginal work, play, home and neighbourhood’,11 and to work collaboratively with the communities, who were ‘invited not only to direct the work of the photographers within each community, but were also given control of the selection of images that were to represent them … It was a process that aimed for a form of co-authorship between photographer and subject, a dynamic interaction between the two actors.12 The project even commissioned the visual anthropologist Eric Michaels to produce ‘A Primer of Restrictions on Picture-Taking in Traditional Areas of Aboriginal Australia’.13 However the project was funded in part by the Australian Bicentenary Authority and broadly echoed the homely national sentiments of the other bicentenary projects discussed elsewhere in this book. Taylor later called the project the first ‘national album of Indigenous Australia’.14

In the 1990s, as documented in Kelly Gellatly’s 1998 survey exhibition Re-Take: Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Photography at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Indigenous photographers began to build powerful individual presences within Australian photography. They created landmarks of Australian art, such as the grid of six large Cibachrome and three large gelatin silver photographs that made up Tracey Moffatt’s Something More, created during a residency at the Albury Regional Art Centre and first exhibited at the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) in 1989. Like Moffatt, many other Indigenous artists also built international profiles. Leah King-Smith’s Patterns of Connection was exhibited in 1992 at the ACP and Queensland Centre for Photography with an immersive bush soundscape recorded by Duncan King-Smith, later touring internationally for two years. In 1994, the curators Fiona Foley and Djon Mundine included Destiny Deacon amongst painters in the Havana Biennial. For the 1992 Biennale of Sydney, Brenda L. Croft had collaborated with the African-American artist Adrian Piper on the installation Conference Call. The work was subsequently shown at London’s Camerawork Gallery in 1994, and in 1995 the biennale’s director Tony Bond included their collaboration, along with Destiny Deacon, in the Australian contribution to Africus, the inaugural Johannesburg Biennale. At the ACP in 1998, Destiny Deacon exhibited Postcards from Mummy, a diaristic journey of reconnection through North Queensland, and four years later it was curated into the major international art exhibition Documenta 11 at Kassel, Germany. More recently, Indigenous artists including Brook Andrew and Christian Thompson have built busy and successful international careers, with Thompson, for instance, installing work in Trinity College and the Pitt Rivers Museum, Cambridge, where he studied. The works of younger artists, like Tony Albert’s computer-generated photo/graphic animated montage I am Visible, 2019, have been digitally projected at vast scale onto the NGA’s exterior.

Importantly too, Indigenous curators have curated exhibitions that have profoundly shaped Australia. Tracey Moffatt curated Mervyn Bishop’s first retrospective, In Dreams, covering his period as a newspaper and freelance photographer from 1960 until 1990. After showing at the ACP in 1991, it toured for another ten years. In 2006, Brenda L. Croft curated the major exhibition Michael Riley: Sights Unseen at the NGA. Riley had died in 2004, and the NGA’s expansive installation brought together his video, multimedia and studio contact sheets, while banking grids and clusters of his framed photographs up the walls to create an immersive life journey for the gallery visitor. In 2007, Indigenous curator Keith Munro presented Ricky Maynard: Portrait of a Distant Land at the Australian embassy in Paris as part of the inaugural Photoquai Biennale of World Images organised by the Musée du quai Branly, before its tour through Australia and the Pacific region. And in 2005, Megan Evans and Maree Clarke curated Black on White at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne, for which the Aboriginal photographers Mervyn Bishop, Gayle Maddigan, Brook Andrew, Lisa Bellear, Dianne Jones and Christian Thompson were invited to represent non-Aboriginality. Exhibitions like this productively complicated received inside/outside, traditional/urban, victim/aggressor dichotomies. More recently Brook Andrew was artistic director of the twenty-second Biennale of Sydney, titled NIRIN.

In all Indigenous photography, the past, particularly the colonial past continues to loom. The formal installation of Judy Annear’s Portraits of Oceania at AGNSW in 1997, and the accompanying catalogue essay, ‘Laying Ghosts to Rest’, by Brenda L. Croft, radically re-empowered the nineteenth century Indigenous subjects of the anthropological and ethnographic portraits in the exhibition. Through a combination of historical scholarship and personal family connection, the Brisbane-based Indigenous curator and researcher Michael Aird has also powerfully reconfigured conventional conceptions of the historical Indigenous portrait. In 1993, for instance, Portraits of Our Elders brought the treasured studio portraits that Aboriginal Queenslanders had commissioned of themselves and their families in the early twentieth century into the Queensland Museum, productively complicating the simplistic colonial gaze/passive ethnographic subject, dichotomous assumptions through which most Indigenous photographs from the past had previously been seen. Aird followed this up with the revelatory Transforming Tindale, at the State Library of Queensland in 2012, where through a process of drawing, the artist Vernon Ah Kee reclaimed the anthropometric photographs originally taken by Norman Tindale for Indigenous memory. Captured: Early Brisbane Photographers and their Aboriginal Subjects, Brisbane Museum, 2014, and Wild Australia: Meston’s Wild Australia Show 1892–1893, University of Queensland, 2017, similarly opened up previously unknown images from the Queensland ‘frontier’ for Indigenous memory.15

Other Indigenous artists and curators have broken new ground in building collaborative models for exhibition production. Examples include Brenda L Croft’s 2017 collaboration with Kalkarindji community and the Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation on Still in My Mind: Gurindji Location, Experience and Visuality, a multimedia, multi-artist exhibition based on the 1966 Gurindji strike (also known as the Wave Hill walk-off).

Regional galleries, in collaboration with regional communities, have also produced important collaborative exhibitions reconnecting the past and the present. In 2004, Sam and Janet Cullen purchased from a London auction thirty-seven portraits of the Gumbaynggirr and Bundjalung peoples of the Clarence River region that had been made by the photographer J. W. Lindt in the 1870s. They donated them to the Clarence River Historical Society and, through the ten-year joint research effort of a group of Indigenous elders and photographic scholars, the previously anonymous ‘ethnographic specimens’ in this collection have been given back their names, their stories, and most importantly their living descendants. From the collection, the Grafton Regional Gallery has produced four exhibitions between 2005 and 2014,16 and one major catalogue: Photographs are Never Still.17 As descendent Shauna Bostock-Smith said about the original gift: ‘It has brought about the connection of Aboriginal people to their ancestors, to their relatives and to their country’.18

-

Catherine De Lorenzo, ‘Photography, Redfern, Proof, Exhibition as Medium’, Visual Anthropology Review, vol. 21, issues 1 and 2, 2006, p. 149. ↩

-

Joanna Mendelsohn, Catherine de Lorenzo, Alison Inglis, Catherine Speck, Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes, Thames & Hudson, Melbourne, 2018, p. 90. ↩

-

Andrew Dewdney, Introduction to Sandra Philips (ed.), Racism, Representation and Photography, Inner City Education Centre, Sydney, 1994, pp. 15-40. ↩

-

Australian Perspecta 1983: A biennial survey of contemporary Australian art, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, p. 19. ↩

-

Gordon Bull, ‘Curating the Field’, AAANZ ‘Inter-discipline’ conference proceedings, December 2014, p. 4. Online at: http://aaanz.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Bull_Curating-in-the-Field.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2019. ↩

-

Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September 1986, p. 4. ↩

-

Geoffrey Batchen and Tracey Moffatt, Photofile, vol. 4, no. 3, 1986, p. 24. ↩

-

Kevin Gilbert, Inside Black Australia: Aboriginal Photographers’ Exhibition, Aboriginal Arts Board, Canberra, 1988. ↩

-

Brenda L. Croft, ‘Controlling our Own Images’, in Sandra Philips (ed.), Racism, Representation and Photography, Inner City Education Centre, Sydney, 1994, p. 119. ↩

-

Jane Lydon, Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights, New South Publishing, Sydney, 2012, p. 25. ↩

-

ibid., p. 256. ↩

-

Penny Taylor, ‘Towards a Collaborative Photographic Practice: After 200 Years’, in Sandra Philips (ed.), Racism, Representation and Photography, Inner City Education Centre, Sydney, 1994, p. 164. ↩

-

Eric Michaels, ‘A Primer of Restrictions on Picture-Taking in Traditional Areas of Aboriginal Australia’, in Sandra Philips (ed.), Racism, Representation and Photography, Inner City Education Centre, Sydney, 1994, 189–202. ↩

-

Lydon, Flash of Recognition, p. 258. ↩

-

Joanna Besley, ‘“Looking Past”: The Work of Michael Aird’, reCollections, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, vol. 10, no. 1, 2015, online at: http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/volume_10_number_1/papers/looking_past. Accessed 28 October 2019. ↩

-

Mendelsohn et al., Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes, 2018, p. 148. ↩

-

Kate Gahan and Ken Orchard, Photographs are Never Still: The J. W. Lindt Collection, Lindt Research Group and Grafton Regional Gallery, Grafton, NSW, 2017. ↩

-

Jane Lydon, Sari Braithwaite and Shauna Bostock-Smith, ‘Photographing Indigenous People in New South Wales’, in Jane Lydon (ed.), Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2014, pp. 58–65. ↩