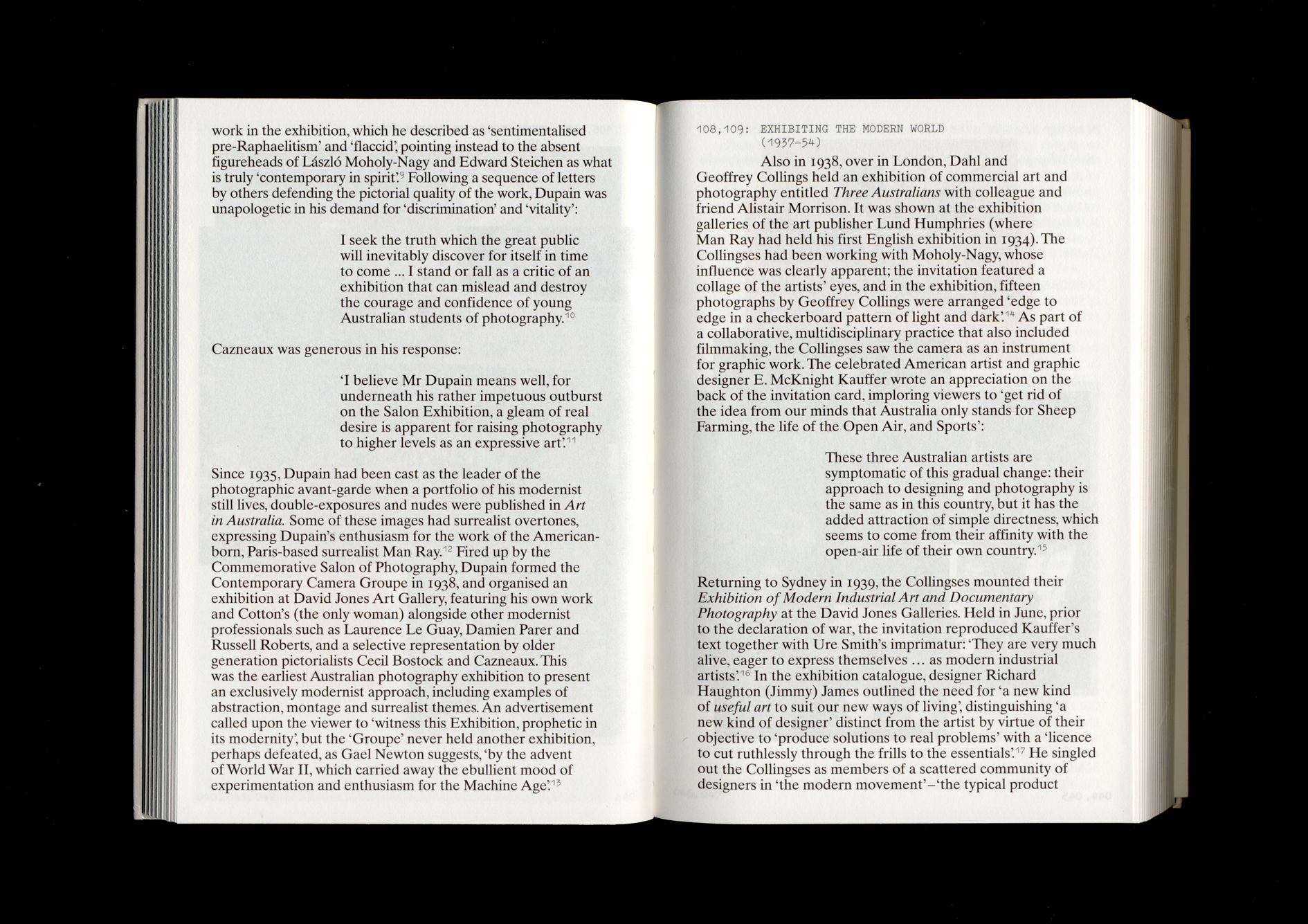

(Installation View, pp. 301–314)

Artists using photography during the 1980s invariably questioned the objectivity of the medium, revealing its partial and political nature through creative images that were obviously constructed (often quoting images from art history or popular culture). This had a significant effect on the physical nature of the resulting work. As curator Isobel Crombie reflected:

Naturalism, so long held to be the foundation of photography, was widely abandoned among Australian photographers in favour of openly declared theatrical fabrications. There was also a shift in the materials used, with black-and-white discretely sized documentary photographs being replaced by large-scaled, opulent productions with photographers often revelling in the lush, saturated colours of the Cibachrome.1

In short, exhibition images adopted a seductive quality and large scale. Partly enabled by technical advances in printing technology, this marked off postmodern photography from both documentary work and conceptual photography of the 1970s. Indeed, by the end of the decade, it became common for press releases to describe an exhibition as featuring ‘works ranging from small-scale photo-documentary works to large, lush postmodernist pieces’.2 There could be no mistaking: postmodern photography was art.

Bill Henson had held his first solo exhibition, at the age of nineteen, at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in 1975 (Of Tender Years, featuring colour studies of young ballerinas). Having made a powerful impression at the first Perspecta at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) in 1981 with an alcove installation of butted-up crowd images, and the fourth Biennale of Sydney in 1982, Henson’s exhibition at Pinacotheca Gallery in Richmond in July 1985 comprised a large set of baroque triptychs in which the interiors of great painting-lined chandeliered museums in Europe were juxtaposed with studio-shots of gothic, junkie-like youths (his Untitled 1983–84 series). Reflecting in 2004 for The Age, Ashley Crawford recalls that the exhibition ‘left critics, curators and collectors spellbound. The dark space at Pinacotheca was lit dramatically, his images protruding through the gloom’.3 However, Adrian Martin was unconvinced, writing in Photofile of Henson’s nostalgia for a classical European old world: ‘One is meant to tremble, before these works, at the manifest presence of things that are disturbing and distressing in their very vagueness and ethereality’.4 While acknowledging the work’s ‘technical and aesthetic qualities, and their momentary ambiguities’, Martin recognised that Henson’s work ‘demands an all or nothing response from those view it’, and took aim at Henson’s romantic sensibility and ‘the suggested narrative and thematic links that arise when images are grouped in particular clusters’.5 Right from the start, Henson paid close attention to the atmosphere of his exhibitions, noting in a 1986 exhibition catalogue:

In any sequence no photograph can be extraneous – the entire series should in fact amount to one ‘image’ which has been articulated into a complex of images. For this reason I take some trouble over the installation of a work – everything having its place yet the possibilities remaining inexhaustible.6

Henson’s 1983–84 series was later exhibited at the Centre for the Arts Gallery at the University of Tasmania in Hobart in 1987. Writing in the catalogue, Rob Horne paid close attention to the installation of the photographs, noting their ‘auratic’ quality as objects, and the musical sense of phrasing:

These pictures as installed have an undeniable power, and it is a power that is largely lost in reproduction … The power of this installation … relies upon the organisation of images itself, upon their presentation as a construction in space … We have here an installation that is clearly more than a collection of individual images, and yet there is no obvious narrative context implicit in their organisation … the overwhelming impression is of a mode of organisation based on rhythm: which is to say, of a visual presentation that is in some ways perhaps more like a piece of music than a photographic exhibition.7

Reflecting on Henson’s exhibitions during this period, Crombie observes: ‘It seemed a whole new way of showing photography and I found it really moving and “immersive” in a way I hadn’t experienced before’.8

Henson’s dramatic use of lighting and his experimentation with new modes of presentation culminated in being selected as the Australian representative for the 46th Venice Biennale in 1995, the first photographer ever chosen for the honour. Australian newspapers remarked on the choice of a photographer for such a prestigious event. Crombie, as the curator, has reflected that it was ‘a mark both of his standing in the arts community and a sign of the incorporation of photography into wider art practice’.9 The exhibition featured Henson’s ‘cut-screen’ images – the paper expressionistically slashed and jagged fragments rearranged over a plywood screen with black gaffer tape and pins – of androgynous adolescents cavorting over suburban cars, glowing out of darkened spotlit space. A critic from The Age described her experience of visiting:

The windows of the pavilion had been covered, so visitors entered darkness to see Henson’s large, unsettling photographic works, their torn white shreds illuminated and thus made more shocking. Early feedback to Henson’s twilight portraits seemed positive.10

The installation toured Australia on its return, and Henson was also represented by cut-screen work in Photography is Dead! Long Live Photography! at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in 1996. Over the following decades, Henson established possibly the most reliable collector base of any art photographer in Australia through his regular exhibitions at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney and Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne. But his work had long courted controversy, and his prestige in the art world did not prevent an exhibition of his work at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery being closed down on opening night, 22 May 2008, amid claims that his work sexualised underage models. The next morning, the front page of tabloid newspaper The Daily Telegraph was set aside for the headline, ‘Child Porn “Art” Raid’, with the Prime Minister Kevin Rudd declaring he found the work ‘revolting’. As a result, public galleries began to remove Henson photographs from their walls, despite no charges being laid.11

Anne Ferran held two important exhibitions at Performance Space in Sydney in the mid-1980s, both alluding to the look of classical art. Carnal Knowledge, her first solo exhibition in 1984, featured a suite of thirteen photographs evoking the sensuality and desire of young women through the lens of new French theories about femininity. In the 1986 exhibition Scenes on the Death of Nature, Ferran presented four large black-and-white photographs, lushly printed in the darkroom, showing the artist’s daughter and her friends draped, reclining and utterly still, evoking early art photography inspired by Pre-Raphaelite tableaux. Enigmatic, beautiful and approximating the size of a monumental marble frieze, the photographs represented another shift away from documentary, alluding to how the image of woman has been produced through visual culture but resisting clear meaning. As Ferran noted: ‘This work ought not need me as the artist to make pronouncements about its meaning. For one thing there is in it very little of a personal vision or private sensibility’.12 Indeed, the exhibition typified a form of postmodern photography based on allegory rather than direct critique. The photographs were originally shown with a set of three faux-classical plinths, with a stack of offset-printed images placed on each – part of a work called The Three Orders (Conception, Assumption, Perpetuation). In her review of the Melbourne showing at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in 1987, the artist Janina Green notes the ‘funerary’ quality and ‘commanding’ scale of the work (at 1.5 metres x 1 metre), but suggests:

This is not an exhibition for the uninitiated. It is intellectual, theory-based, elitist and puzzling. Much of the work’s interest comes from the intellectual ramifications – the catalogue notes, Adrian Martin’s enthusiastic essay in Photofile, the feminist fervour in the Sydney scene, the aesthetic problems of new photography, and so on.13

Art schools, which had increasingly incorporated photography from the late 1970s, became important in producing photographers who saw themselves as distinctly different from the earlier generation of 1970s photographers. Because of their art school training these photographers were theoretically informed and sub-culturally engaged. As Catriona Moore puts it:

These practitioners stood apart, amongst other things, for their open approach to contemporary cultural theory. Poststructuralist psychoanalytic, semiotic and communications models were investigated to see how they helped explain TV watching, cinematic pleasure, sub-cultural aesthetics and other popular photographic realms.14

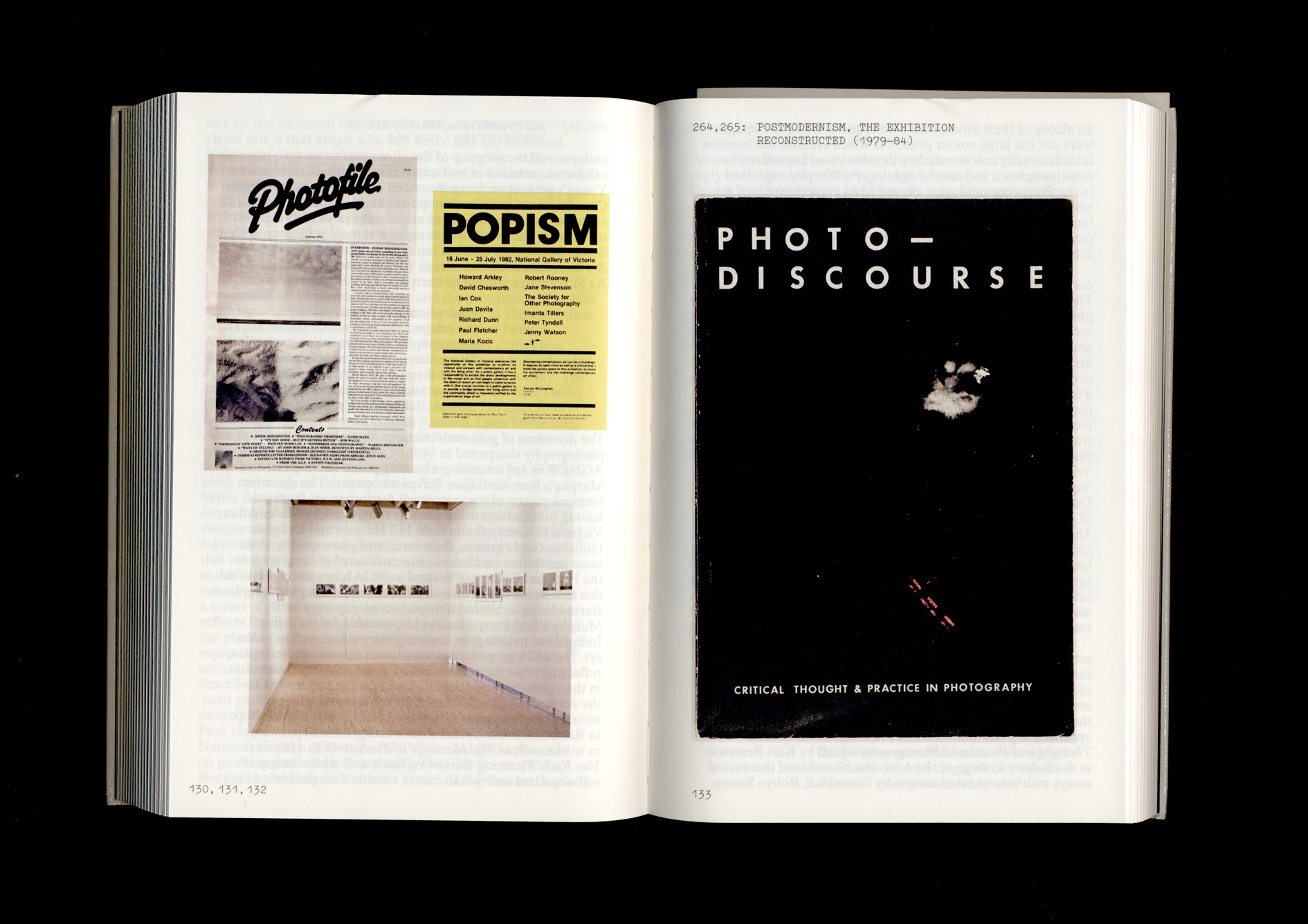

‘Dressed to kill and with nowhere to go’, in Moore’s words, their work intersected with the expansion of artist-run spaces and new commercial galleries. Self-curated exhibitions such as After the Artefact at the Wollongong City Gallery in 1984, Killing Time at Sydney’s commercial Mori Gallery and Suspending Belief at Brisbane’s The Observatory, both in 1986, joined a variety of exhibitions where photography interacted with painting, performance, music and video at artist-run spaces such as Art/Empire/Industry and Art Unit (which both ran for a few years in Sydney from 1982), Union Street Gallery 1985–86, and First Draft which commenced in 1986. Solo photography exhibitions at commercial galleries also shifted towards the postmodern and the sculptural. For Combust, at Brisbane’s Michael Milburn Galleries in 1991, Jay Younger made metre-square montages of physical objects and computer-generated elements. Each chromatically intense Cibachrome was splayed between steel cables bolted to the floor and ceiling and lit each with a single spotlight like ‘some kind of corporate insignia revolving above this or that city edifice’.15

By 1986, the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP), under the new direction of Denise Robinson (previously of George Paton Gallery), was more aligned to this new avant-garde, abandoning its brief emphasis on community-based work under Tamara Winikoff (1982–85) that was itself a reaction to the criticism of previous director Christine Godden’s emphasis on the fine print. The ACP was now a long way from its role in the mid 1970s as a place to canonise modernist photographers such as David Moore and Max Dupain. Geoffrey Batchen took over the editorship of Photofile, and in 1986, as part of the Biennale of Sydney, Martyn Jolly, co-author of this book, curated the ACP satellite exhibition Elsewhere: Displacements within Australian Photography including Graeme Hare, Jacky Redgate, Robyn Stacey and Anne Zahalka, all of whom produced photographs which referred to visual traditions other than the traditionally photographic.16 In 1987, Zahalka presented her iconic series Resemblance, a series of costume drama portraits that self-conscious play on seventeenth century Dutch genre paintings, where people are staged with the accoutrements of their trade. Produced in 1986 during a residency in Berlin, and touring extensively, the large Cibachrome prints, then favoured, provided the artificially rich colours and glossy surface to rival the impact of painting. Also at ACP in 1987, Sandy Edwards curated Image Perfect: Australian Fashion Photography in the 80s with Polly Borland, Monty Coles and Grant Matthews among other commercial practitioners. Edwards approached fashion photography from the perspective of someone actively involved in feminism, having been part of a collective of women photographers, the Blatant Image. Even so, the field of fashion photography was dominated by men and she managed to include only two women among the eleven photographers exhibited. Edwards expressed interest in the narrative complexities of the fashion spread, as one of the few ‘places a female protagonist (or heroine) at the centre of the action’. As the first time a curated collection of contemporary Australian fashion photography had been exhibited in Australia, it signalled a new intersection between commercial and artistic photography, although Edwards has reflected that there was ‘a lot of bemusement and questioning as to why I was doing it’.17

By 1988, the year of Australia’s bicentenary, postmodernism had become mainstream, standing for a wide variety of approaches to photography that departed from the purist fine print or documentary mode. In Melbourne, at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the newly appointed senior curator of photography Isobel Crombie curated Excursions into the Postmodern: Five Melbourne Photographers: Rozalind Drummond, Rose Farrell and George Parkin, Graeme Hare, Kevin Wilson.18 Crombie recalls that when she started at the NGV, she entered the photography gallery on the third floor after hours to find light streaming through the holes in a wall along a line where framed prints had been consistently hung. For the show, she adopted the radical approach of pinning unframed photographs to the wall. All around the country, 1988 was a time to take stock. Joyce Agee curated the eclectic survey The Thousand Mile Stare at ACCA for the new Victorian Centre for Photography, and at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Helen Ennis presented Australian Photography: The 1980s, to accompany Gael Newton’s major historical survey Shades of Light. Perhaps an effect of the sustained reflection on national identity, the following year generated two of the most memorable bodies of contemporary Australia photography. Zahalka had long explored national mythologies in earlier photomontages of paintings by Frederick McCubbin and others. Her overtly theatrical series Bondi: Playground of the Pacific, 1989, evolved from a six-month residency at the Bondi Pavilion, in which she used the beach and a painted backdrop to re-present stereotypical imagery of Australia’s white settler inhabitants. For her playful parody of Max Dupain’s iconic 1937 photograph, Sunbaker (made famous through a 1975 retrospective at the ACP), The Sunbather #2, 1989, she staged an androgynous redhead lying on the beach against a blue sky. Another work, The Bathers, takes inspiration from the celebrated Charles Meere painting Australian beach pattern, 1940, but presents a cast of people who more accurately reflected the multicultural nature of contemporary Sydney. Zahalka first presented the large colourful images in an exhibition at the Bondi Pavilion in December 1989.

A few months earlier, the ACP had premiered Tracey Moffatt’s signature work, Something More, 1989, which had been commissioned by the Albury Regional Art Centre in 1989 while the Indigenous artist was in residence there. A series of nine staged photographs – six colour-saturated Cibachromes and three high-contrast black-and-white images – Something More tells an indeterminate narrative of racism and desire set in the sub-tropical north of Australia. The protagonist of the photo-drama, played by Moffatt herself in a red, scissor-hacked cheongsam, is pictured among a cast of caricatures – an alcoholic father, a lascivious blonde woman and jeering schoolboys – against a painted studio backdrop. Reflecting Moffatt’s love of pop culture and her filmmaking background (she made Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy in the same year), the series is usually shown in black frames abutting one another in a line, enhancing the sense of a cinematic narrative. This was Moffatt’s first solo show at the ACP and its significance to postcolonial ways of thinking about Australia was quickly apparent, with the NGA immediately acquiring the work.

-

Isobel Crombie, ‘Photography in Australia’, in Lynne Warren (ed.), Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, Routledge, New York, 2006, p. 89. ↩

-

This is how the exhibition Twenty Contemporary Australian Photographers was described in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1990 when it was shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in what is presumably a regurgitated press release. ↩

-

Ashley Crawford, ‘Henson’s art of darkness’, The Age, 26 June 2004. Online at: https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/hensons-art-of-darkness-20040626-gdy42c.html. Accessed: 28 October 2019. ↩

-

Adrian Martin, ‘Bill Henson and the Devil, Probably’, Photofile, Spring 1985, p. 21 ↩

-

ibid., p. 22 ↩

-

Bill Henson, Mnemosyne, Scalo in association with the Art Gallery of New South Wales Press, Zurich, 2005, p. 241. ↩

-

Rob Horne, Bill Henson: Untitled 1983–84, exhibition catalogue, University of Tasmania, Centre for the Arts Gallery, Hobart, 1987. Given Henson’s alignment with classical music, it is perhaps unsurprising that Australian orchestras have invited him to collaborate with them on multiple occasions, most recently Luminous: A Visual and Musical Immersion, with the Australian Chamber Orchestra in 2019, touring to capital cities and the London’s Barbican Centre, in which, according to a newspaper advertisement, music is ‘set to an arresting and dramatic backdrop of Bill Henson’s imagery onscreen’. ↩

-

Isobel Crombie, personal email communication with Daniel Palmer, 21 June 2019. ↩

-

Isobel Crombie, ‘Photography in Australia’, in Lynne Warren (ed.), Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, Routledge, New York, 2006, p. 90. ↩

-

Sonia Harford, ‘Cocktail of style is life in Venice’, The Age, 14 June 1995, p. 28. Henson’s work was displayed in Philip Cox’s original ‘temporary’ Australian pavilion at Venice, which opened in 1988 and was dismantled in 2014 to make way for a permanent pavilion designed by Denton Corker Marshall. ↩

-

The Henson controversy generated a media frenzy and eventually an entire book dissecting the paranoia around images of naked children by David Marr, The Henson Case, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2008. ↩

-

Anne Ferran quoted in: Helen Ennis, Australian Photography: The 1980s, An Exhibition from the Australian National Gallery Sponsored by Kodak, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988, p. 76. ↩

-

Janina Green, ‘Escape to the world of subtlety’, Melbourne Times Review, 25 March 1987. ↩

-

Catriona Moore, ‘Photography at the Unit’, Final Verse: Art Unit 82–85, Art Unit, Sydney 1988, pp. 15–18. ↩

-

Nicholas Zurbrugg, ‘Jay Younger, Combust, Michael Milburn Gallery’, Eyeline 16, Spring 1991, p. 38. ↩

-

In 1988, Redgate was also included in an exhibition of the same title, Elsewhere – subtitled ‘photo-based work’ (as opposed to ‘photography’) – curated by James Lingwood at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, also including Julie Rrap, Jeff Gibson, Bill Henson. ↩

-

Sandy Edwards, ‘The Eighties in Retrospect’, Photofile, no. 71, 2004, p. 61. ↩

-

The title to the show was an echo of a seminal event at the University of Sydney in 1984 – Futurfall: excursions into post-modernity* – with the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. ↩