(Installation View, pp. 93–100)

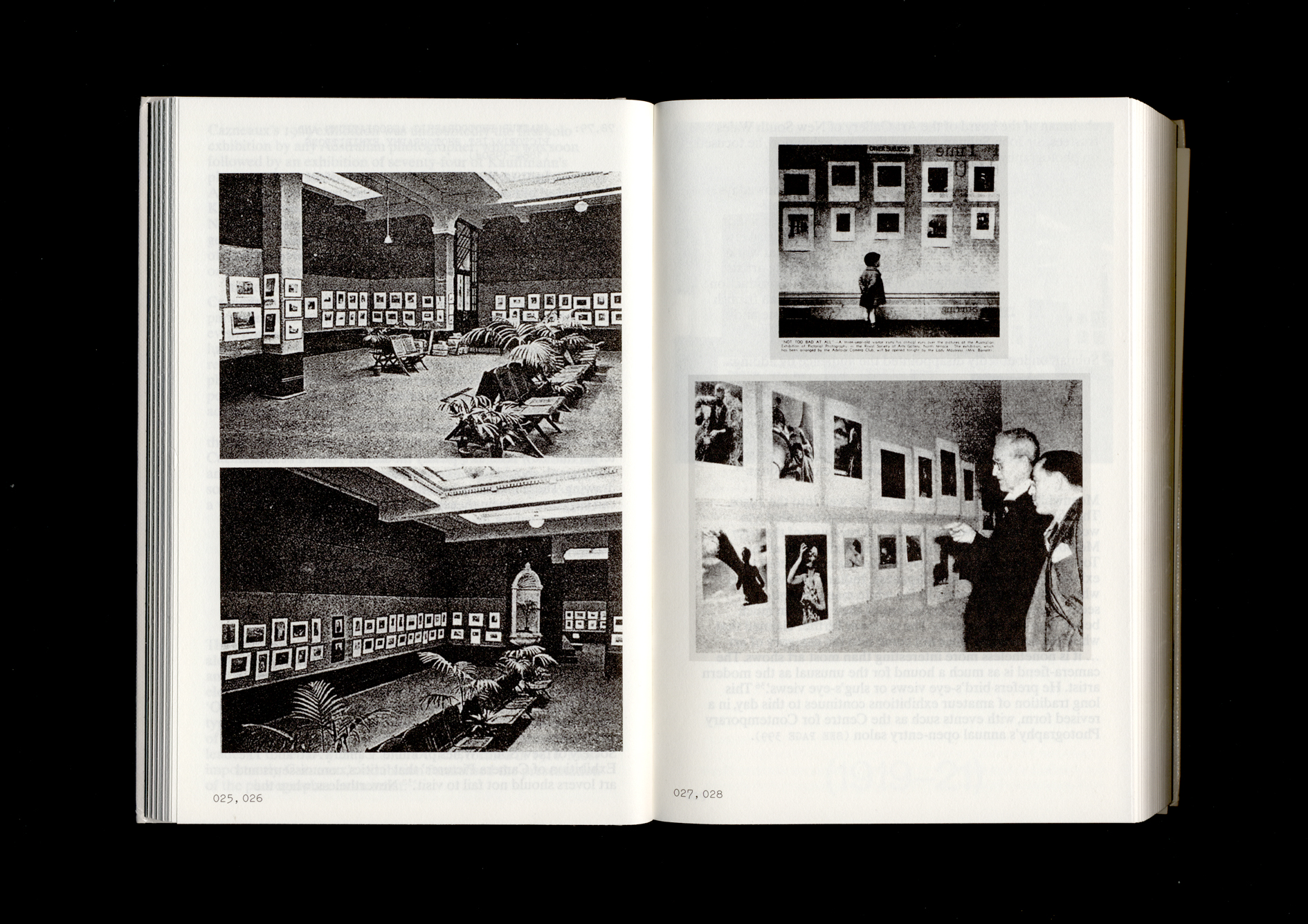

In the mid nineteenth century, a photographer’s studio was an important hybrid space for exhibiting daguerreotypes, prints and the latest in new technologies. But with the development of other forms of promotion, including advertisements and postcards, professionals had less of a commercial imperative to directly invite the public to enter their ‘open studio’. As a result, by the late nineteenth century amateur photographers had become more actively engaged in the act of exhibiting than professionals were, particularly through the annual salons of various amateur associations.

Nevertheless, enterprising professionals made use of window displays and their studio spaces as impromptu settings for exhibition. For example, Thomas Foster Chuck (praised for his work in the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition) established himself as ‘artist and photographer’ in the newly built Royal Arcade in Melbourne in 1868. Between 1870 and 1872, he collected photographs of early settlers for his magnum opus, a mosaic of 713 tiny portraits of explorers and early colonists of Victoria composed into huge shield-like shape, measuring 1.5 metres high and 1.2 metres wide. To obtain the images, Chuck photographed some of the surviving settlers, copied negatives of others and photographed paintings of the more famous. Completed in 1872, it was displayed at the State Library of Victoria, where Chuck was able to sell smaller copies of the composite image to the public, as well as individual cartes des visites of the sitters. The following year, on a Saturday evening in August, there was ‘quite a rush at the window’ of the Bendigo photographer N. J. Caire to see ‘two interesting photographs’.1 Each full-plate photograph featured almost microscopic detail. One was a copy of an ‘old engraving, which includes pictures of all the principal events in the life of Christ’, the other was a mosaic of 274 tiny portraits of ‘The Ministers of the Wesleyan Australasian Conference 1873’.2 The mosaic photographically combined visual and textual information:

The figures are located in a manner easy for reference, every one bearing a number corresponding with one attached to the name of the rev. gentleman which appears in a list photographed in printing on the margin … In this collection we recognise the faces of many Wesleyan ministers who in times past were favourably known in this district. A great demand has set in for them, and Mr Caire has already sent hundreds to all parts of the Australian colonies.3

Because it was at street level, the photographer’s display case became a compressed but very powerful exhibition space. One of the most famous photographs from the State Library of New South Wales Holtermann Collection is the c.1872 portrait of Charles Bayliss and studio operator James Clifton standing either side of the display case of Beaufoy Merlin’s A&A Photographic Company. Although the studio was in the middle of the goldfields, the views on display in the case are of the grand building and magnificent harbour of distant Sydney. Much later, in the twentieth century, the display case was just as important. For instance, in 1959, Wolfgang Sievers arranged a display in his Australia Arcade showcase based on his 1957 trip to the Rum Jungle uranium mine in the Northern Territory, and Weipa in North Queensland, the site of a bauxite mine and an Aboriginal mission. The case displayed a view of the entrance to the uranium processing plant and Indigenous and white workers sorting and testing bauxite samples in Queensland. Sievers also mounted in the showcase geological samples, perhaps uranium ore and bauxite, that were neatly labelled. Sievers had made the trip for the Department of Overseas Trade. Eight years later, he used the same showcase to protest against the Vietnam War.

For women photographers, the studio became very important as both a creative space and a controlled exhibition space. For instance, Olive Cotton very successfully ran Max Dupain’s large Sydney studio during World War II, and in 1964 re-established her practice by opening her own studio and darkroom in Cowra, New South Wales, away from the farm where she lived with her second husband.4

The practice of using the photographic studio as an exhibition space was exemplified in 1928 when Ruth Hollick held an exhibition of children’s portraits. This is most likely the first solo exhibition by a female photographer in Australia. Hollick – along with her business and life partner Dorothy Izard – specialised in naturalistic portraits of families and children, as well as social and fashion photography. Following Mina Moore’s retirement in 1918, they moved into her studio in the Auditorium Building on Collins Street, and during the economic boom of the 1920s Hollick exhibited in photography salons locally and abroad, often winning medals. She exhibited on several occasions at the colonial exhibitions of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, at the Chicago Photographic Exhibition in 1927, was the only woman to participate in the Melbourne Exhibition of Pictorial Photography in 1929, and in the same year showed with the Photographic Society of New South Wales. Hollick had studied at the National Gallery School and was a lifelong friend of painter Frederick McCubbin. Between 1920 and 1928 Hollick and Pegg Clarke, who specialised in gardens and landscapes, shared most of the Melbourne commissions for The Home and Art in Australia magazines with Harold Cazneaux in Sydney.5

Hollick’s success during the 1920s enabled her to move into an expanded studio next door, occupying an entire floor in the newly built Chartres House 1926 at 165 Collins Street. There, she held her 1928 exhibition, which comprised more than one hundred and fifty portraits of children. The Argus newspaper described the scene of the ‘very large gathering’ in detail:

The studio is a picturesque room … Slanting windows were veiled with ivory muslin, or curtained with dull green and blurred cretonnes. Jars of golden broom and damask roses were arranged about the room, and the child studies were fastened on long screens running the length and width of the studio.6

Hollick’s documentation of the exhibition shows the images carefully pinned to a series of such screens. Noting the portrait’s ‘at once natural, artistic and unselfconscious’ qualities in her opening speech, Mrs J. G. Latham, the wife of the Attorney-General of Australia, declared that ‘it is now universally acknowledged that a woman has the right to earn her living in any profession she may select … I think we can all agree that in such a career as that of photographic art they may be said to excel’.7 The Melbourne correspondent for the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail went even further, arguing that ‘in Miss Hollick we have one of the world’s most gifted photographers of childhood’.8

-

Bendigo Advertiser, 25 August 1873, p. 2. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton, Fourth Estate, Sydney, 2019. ↩

-

Pegg Clarke held an exhibition at the Auditorium Building, Impressions of Melbourne, in 1931 with her partner, the painter Dora L. Wilson. See Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather, Australian Women Photographers: 1840–1960, Greenhouse Publications, Melbourne, 1986, p. 69. ↩

-

‘Exhibition of Child Portraiture’, The Argus, Melbourne, 1 November 1928, p. 10. ↩

-

‘Exhibition of Child Portraiture’, The Argus, Melbourne, 1 November 1928, p. 10; As Hall and Mather document (Australian Women Photographers, p. 74.), women had been especially active in professional studios in the 1890s, and the 1907 Exhibition of Women’s Work in Melbourne included sixty-five women photographers representing every state, including a special display of portraits by Alice Mills. Women were very active in amateur photographic associations in the 1920s, with almost a quarter of the entries in the pictorial section of the 1923 Adelaide Camera Club’s Annual Exhibition by women, although the more conservative photographic societies continued to be dominated by men. ↩

-

Gladys Hain, review of Ruth Hollick’s 1928 exhibition, The Illustrated Tasmanian Mail, 21 November 1928, p. 11. Cited in, Susan van Wyk, The Paris End, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2006, p. 54. ↩