(Installation View, pp. 169–178)

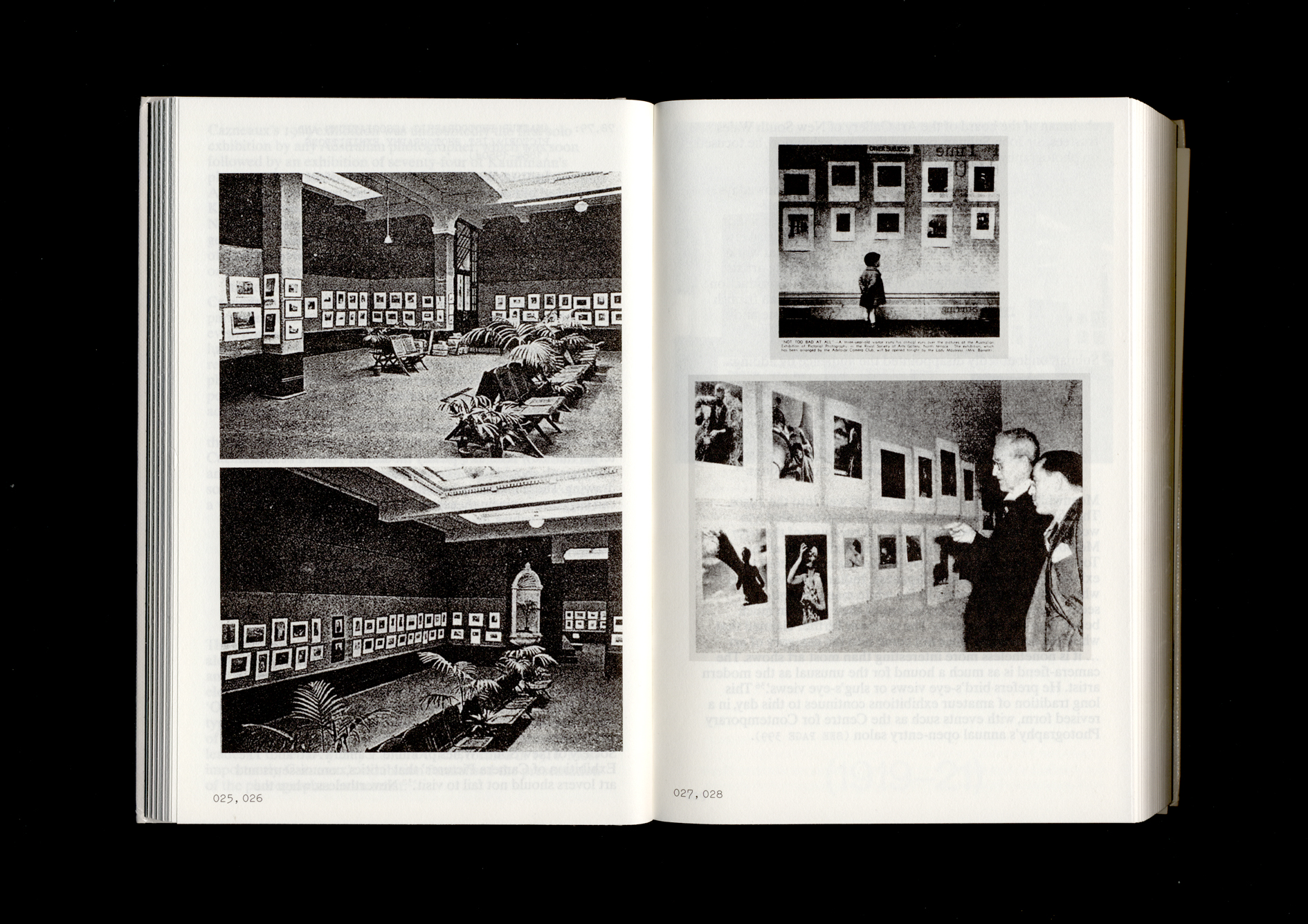

Precisely at the moment that ‘creative photography’ was being accorded a status worthy of exhibition in Australia’s state art galleries, an entirely different style of exhibition practice involving photography was emerging. Centred around a new wave of artist-run and experimental galleries, a younger group of avant-garde and internationally networked artists such as Dale Hickey, Simon Klose, John Nixon and Robert Rooney in Melbourne, and Ian Burn, Tim Johnson and Mike Parr in Sydney, adopted the seemingly banal snapshot above the composed artistic photograph to explore formal and conceptual ideas. In their artworks, individual photographs – typically in repetitive series – became tautological illustrations to an idea, leading to a distinctively different form of exhibition practice involving photography.

Undoubtedly, the first Australian exhibition to include conceptual photography was held in August 1969 at Pinacotheca Gallery in St Kilda.1 It featured Ian Burn and British artists Mel Ramsden and Roger Cutforth, all then based in New York. Ramsden had lived in Melbourne for a couple of years in the early 1960s and, like Burn, had been included in the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) Field exhibition of abstract Australian art in 1968, and would become a key figure in the Art and Language group. Living in New York, Burn had abandoned painting and started using ‘invisible’ materials such as glass, acetate and mirrors, which turned the gaze of the beholder into a self-reflexive encounter. He also began to use Xerox machines as part of his art process, commencing with Systematically Altered Photographs, 1968, phantom dotted renderings of black and white photographs picturing suburban Australian scenes sourced from the Australian News and Information Bureau’s in-house magazine. For the 1969 exhibition, Burn asked Pinacotheca gallerist Bruce Pollard to install four of his 1969 Xerox Books in ‘a library like situation’ and sent a photographic set-up of a reading table he had built in New York.2 Burn’s books recorded ‘a process of successively re-copying the previous copy of what had been originally a blank sheet of paper’.3 Each book contains a detailed description of the precise hour, day and location of the photocopying shop, as well as ‘a gradual build-up of electronic “snow”’.4 Although ‘the idea of placing books in a gallery was unheard of in Australia in the late 1960s’,5 at least two of the books sold, and the exhibition attracted the interest of John Reed, Director of the Museum of Modern Art, who briefly described Cutforth’s work in a letter as a room with a straight row of thirty small colour photos of the sky and clouds.6 Reed neglected to mention the other two parts – an accompanying calendar and location data – crucial to Cutforth’s understanding of the images as ‘recordings’.

No doubt emboldened, Dale Hickey, also better known as an abstract painter, exhibited 90 White Walls at Pinacotheca’s new space, an old hat factory in Richmond, Melbourne, in 1970. As with so much conceptual artwork, the title was literal: the work comprised bald black-and-white documentation of ninety white walls, labelled and stored in a box as index cards. As the artist reflected in an interview: ‘They were photographs of white walls, ninety of them in different locations throughout the Melbourne suburbs … it was a repetition of similar elements and allowing the spectator very, very little to get into’.7 Offering no particular insight, self-expression or moral, the series of monochromatic grey photos showed nothing – they simply pointed to the world and made no effort to understand or beautify it. That the light meter had underexposed the walls might have been an exercise in camera vision (akin to those of British artist John Hilliard around the same time), but was more likely an unintended technical error.

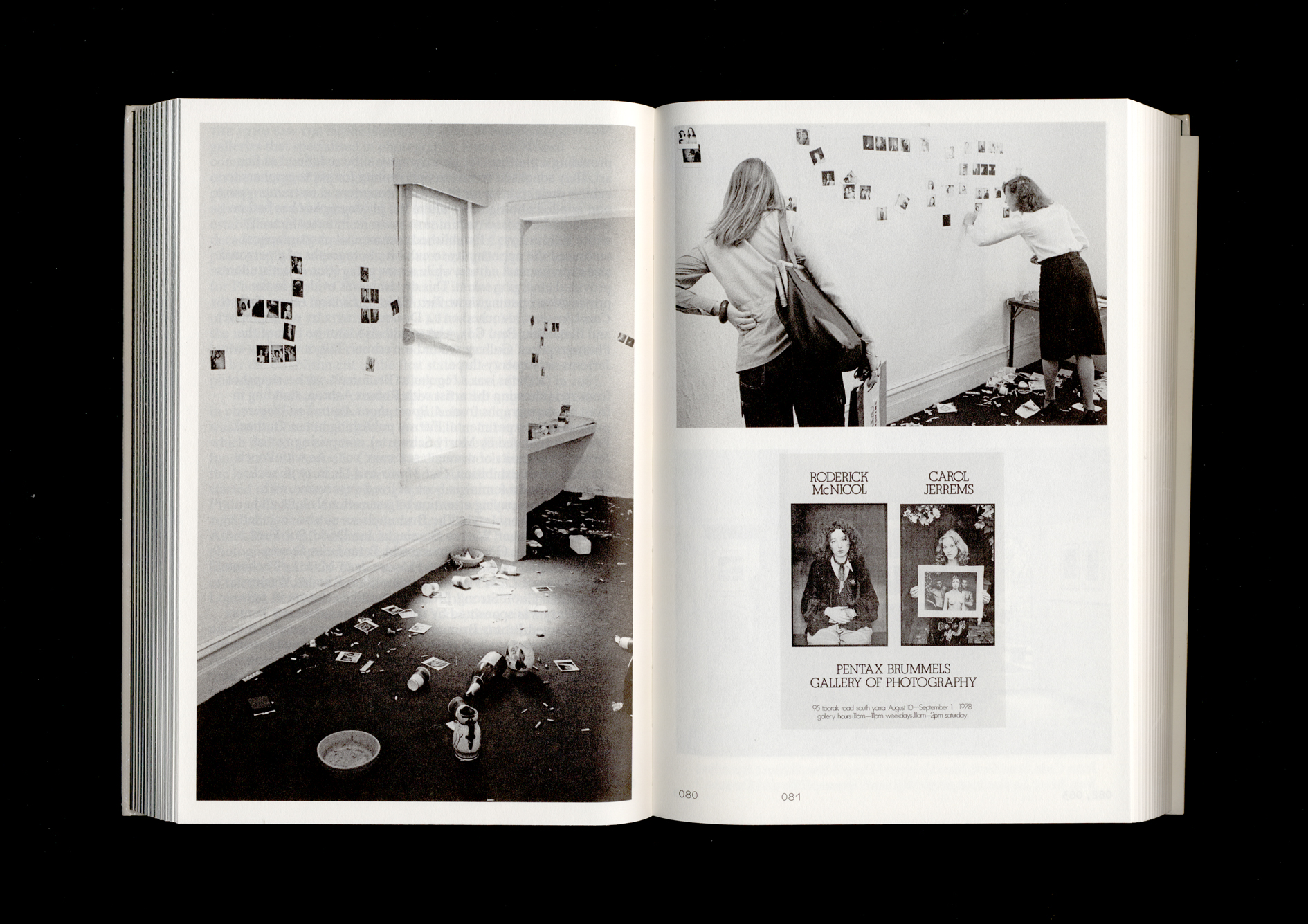

Robert Rooney and Simon Klose employed similarly reductive forms of serial photography at Pinacotheca, inspired by American artists Ed Ruscha – who famously declared that his photographs were ‘simply a collection of “facts” … a collection of “readymades”’8 – and Douglas Huebler, who claimed to ‘use the camera as a ‘dumb’ copying device that only serves to document whatever phenomena appears before it through the conditions set by a system’.9 Rooney would himself suggest in 1975, ‘the camera is a dumb recording device’ that is ‘not the same as seeing’ and ‘often seems to organise the material itself’.10 In a complex collaborative exhibition in August 1972 at Pinacotheca, Rooney and Klose engaged in an imitative process of indexical sampling, imitating each other’s style. The exhibition comprised four series of photographic images and an installation of bluestone pitchers. Rooney’s N.E.W.S.,1972, was produced by placing the camera on the floor, with each of the four sets of images corresponding to a distinct space within the building – three indoors and one outside – in which the work was executed. In the exhibition, the images were arranged in four rows according to the direction towards which the camera had been facing at the moment of exposure (ordered, as indicated by the title, north, east, west, south). Another work by Rooney imitated Klose’s earlier experiments that had begun with Room Documentation, 1970, in which photographs were taken from the four corners of the room, and then ‘presented alongside an isometric projection of the gallery in which ruled lines describe the direction of the camera for each exposure’.11 That the exhibition space was so central to the realisation of the work can be understood as an early and rare example of photographic site-specificity. For his part, Klose imitated Rooney’s photo-grid format in his work Car Park, 73 Queens Lane, City South, 1972, a succession of downwards-facing photographs of a vacant car park from the aerial vantage of a ladder, and 10 Chairs,1972, ten black and white snapshots of chairs displayed in two even rows, accompanied by a typewritten list of the suburbs in which each was taken. The arrangement of images into the neutral format of the grid was by then an established trope in international conceptual work, notably Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographic typologies of industrial structures.

Hickey, Rooney, Klose had previously exhibited together in Sydney in 1971 at the exhibition Four Artists Using Photography at Inhibodress, alongside the work of Cutforth (with whom Rooney engaged in an extended letter exchange). That exhibition included an earlier version of Klose’s room documentation (presented out of context). Inhibodress was Australia’s first artist collective – co-established in 1970 by Mike Parr with Peter Kennedy and Tim Johnson – and a pioneering venue for Australian performance and video art. As with the video, much of the photography exhibited at Inhibodress took the form of documentation of performances involving various degrees of risk. Johnson, for instance, assembled photographic documentation of a series of ephemeral installations made while travelling in Europe into a show he called Out of the Gallery – Installation as Conceptual Scheme in April 1971. Public fitting, 1972, one of his more notorious series of photographs, recorded young women on Sydney streets as their dresses were blown up by the wind, which he understood less in terms of voyeurism and more in terms of an unscripted public performance.

The influence of conceptual approaches to making photographs could be seen through the 1970s in work such as Wes Stacey’s The Road, 1975, a diaristic road trip between 1973 and 1975, presented as serial snapshots at the Australian Centre for Photography, and Micky Allan, My Trip, 1976, a feminist road trip in which she photographed everyone who spoke to her on the journey, and offered the camera to those same subjects to photograph anything they chose. Allan recorded everything that was said to her and turned the results into a ‘newspaper’ for sale in newsagencies, with the simple but generative ‘instruction’ recalled in a handwritten text on the second page. My Trip was exhibited in 1976 at the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide in Post-Object Art, Australian and New Zealand: A Survey – both pinned to the wall and displayed on a high wooden desk with a stool – with Sue Ford, John Lethbridge, Mike Parr, Imants Tillers and others.

A more overtly political approach underpinned Virginia Coventry’s Here and There: Concerning the Nuclear Power Industry, 1979, in which photocopied newspapers and episodic photo-panels are overlaid with Coventry’s handwritten annotations. The four-metre wide installation asks questions both about the nuclear industry and how we look at photographs, notably the relation between camera operator and viewer. As Coventry commented, she ‘wanted to use photographs taken by many people to signify, through a collective witness, that we were already experiencing the consequences of living in the nuclear society’ and that the words she ‘drew’ on the image also ‘represent a number of different speakers’.12 Numerous exhibitions of photography at the George Paton Gallery in Melbourne were driven by a similarly conceptual approach, blurring into postmodernism with exhibitions such as Judy Annear’s Frame of Reference, 1980, which included Coventry’s work.

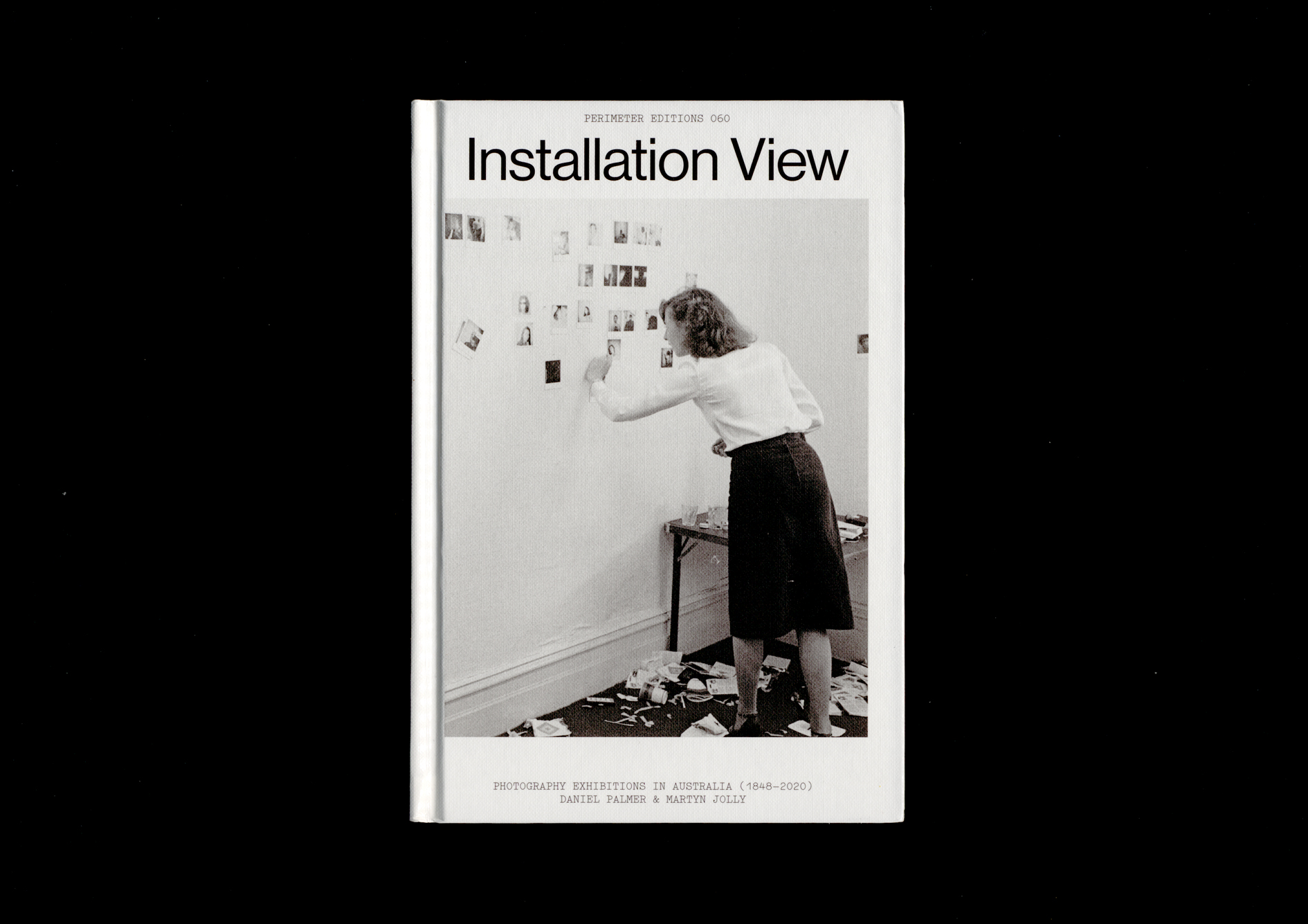

In 1981, John Nixon’s Society for Other Photography adopted a more formal approach: a double line of Polaroid photographs presented along bare white walls at his Art Projects space in Melbourne. Nixon conceived of Society for Other Photography as a democratic art project, with the accompanying manifesto:

THE SOCIETY FOR OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY IS ON THE ONE HAND A RADICAL/AMATEUR APPROACH TO PHOTOGRAPHIC PRACTICE, AND ON THE OTHER, A ‘COLLECTION’ OF ‘UNSKILLED/SKILLED’ SX70 POLAROID PHOTOGRAPHS. THE SOCIETY FOR OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY HAS A CATHOLIC/ANALYTICAL ATTITUDE TO POTENTIALLY INCLUDE ANY GIVEN REAL/PHOTOGRAPHIC REALITY WITHIN ITS PRACTICE I.E. PHOTOGRAPHS OF ‘ANYTHING IN THE WORLD’/‘ORDINARY SUBJECT MATTER’. THE SOCIETY FOR OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY USES A POLAROID ONE STEP 1000 CAMERA AND SX70 FILM. THESE ARE USED FOR THEIR LOW COST PER UNIT ‘ORDINARY’/‘AMATEUR’/‘FUN’ STATUS. THE SOCIETY FOR OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY FEATURES ‘VIEWS OF THE WORLD’ FROM PERSPECTIVES ABOVE AND BELOW/LEFT AND RIGHT/UP AND DOWN/FRONT AND BACK/ACQUIRED AND TAKEN/FUN AND SERIOUS/ANON AND KNOWN.13

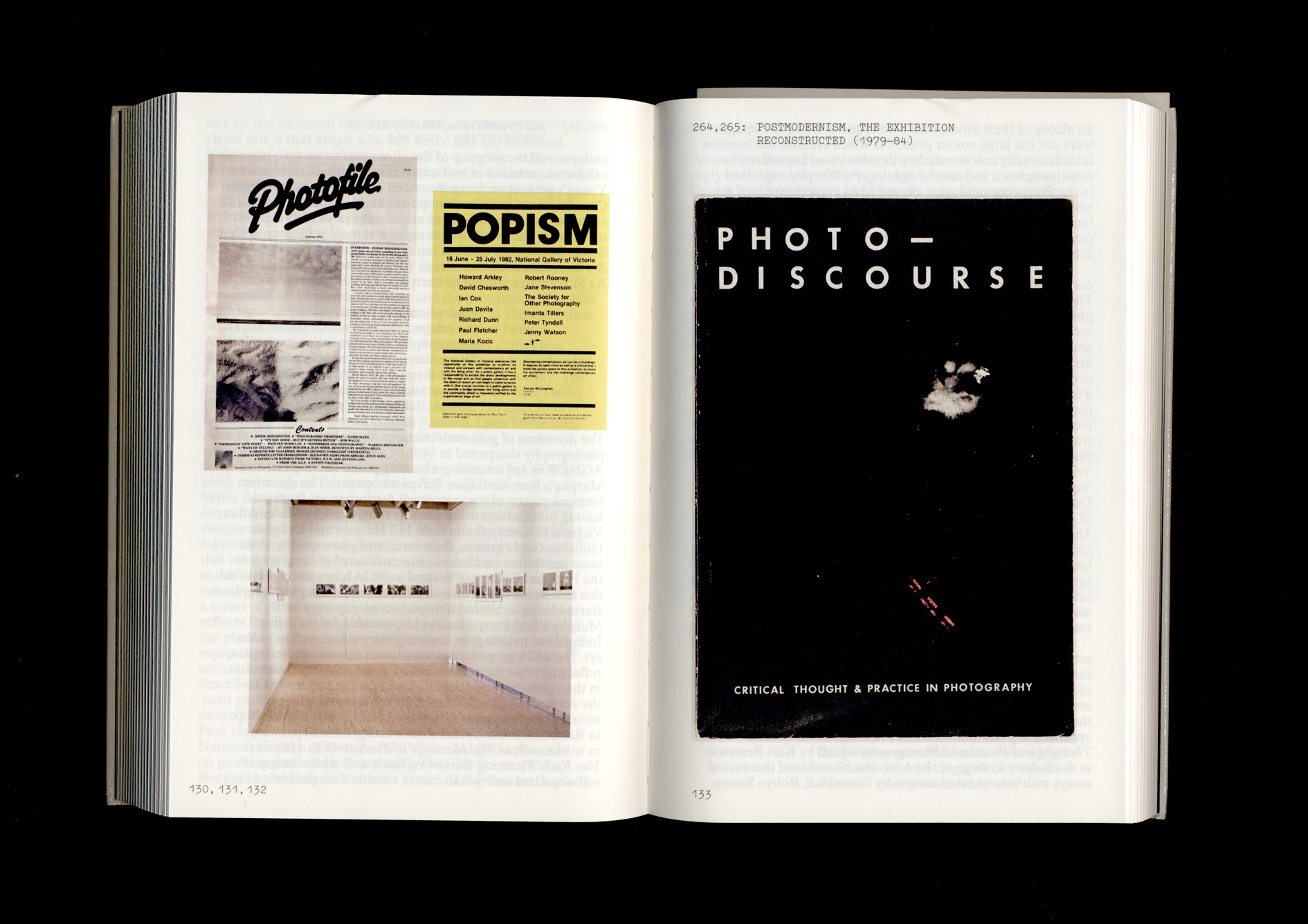

In reality, the amateurism was something of a pose, and Nixon’s interest in the Polaroid’s saturated and painterly colour, as well as its intimate, immediate and democratic character, was understood by curators as an intelligent contribution to visual art. Paul Taylor included a version of the work in his landmark Popism exhibition at the NGV in 1982, writing of how the work’s co-authoring offered ‘no single perspective; the realm of the photographic is extended way beyond personal vision to absorb the uncharted and anarchic aspects of cultural visibility’.14 Bernice Murphy also selected Society for Other Photography for the second Perspecta in 1983, by which time the discourse of photoconceptualism had given ground to postmodernism. Coincidentally, for the same Perspecta, Murphy arranged a row of thirty-three Instamatic photographs taken by Indigenous painter Jimmy Barnabu, accompanied by an audio cassette player, documenting daily life in Ramingining, in the Northern Territory.

The legacy of conceptual approaches to both the making and exhibiting of Australian photography are difficult to underestimate. On the one hand, the serial and taxonomic mode of presentation remains a critical mode for the production and display of photographs. In 1999, for instance, Mathieu Gallois presented a photographic record of sleepy passengers aboard a Boeing 747 jet (Flight 934-B, 1999). All 385 passengers were photographed in individual snapshots presented along an entire wall of Canberra Contemporary Art Space (and the following year at Centre for Contemporary Photography), arranged on the wall in the shape of the seating plan of the aircraft. As the artist proposed, ‘the function of the work does not so much rest with its value as accurate documentation or description, so much as an invocation of air travel as a metaphor for the subjective experience of the individual within a public context’.15 A kind of August Sander of the jet age, with a good dose of deadpan humour, the resulting typology assumed a sculptural dimension achievable only in the exhibition space. At the same time, social history and art museums also present uncurated photographic ‘walls’ extracted from their digital databases, which echo the neutral information systems of conceptualism.

-

Pinocotheca Gallery was a commercial gallery established by Bruce Pollard in a house in St Kilda, interested in showing post-object and conceptual art. ↩

-

Ian Burn, quoted in Ann Stephen, On Looking at Looking, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 123. ↩

-

ibid., p. 125. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

John Reed, personal letter quoted in Stephen, On Looking at Looking, p. 127. This work is now in the NGV Collection, titled Noon Time-Piece (April), 1969. The work came with extensive instructions: ‘The Recordings in this piece should be placed edge / to edge on a wall in a horizontal sequence 1 to 30. / They can be attached to the wall with transparent / photo mounting corners. It is essential that they are / presented in the right sequence of the numbers on the / reverse side. / The other two parts should be located on a wall nearby. Roger Cutforth / May 69.’ ↩

-

‘James Gleeson Interviews: Dale Hickey’, 1 May 1979, National Gallery of Australia Learning and Oral History Collection, Canberra. Online at: https://nationalgallery.com.au/Research/Gleeson/pdf/Hickey.pdf. Accessed 15 September 2019. ↩

-

John Coplans, ‘Concerning “Various Small Fires”: Edward Ruscha Discusses his Perplexing Publications’, in Edward Ruscha and Alexandra Schwartz (eds.), Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, pp. 23–7. ↩

-

Douglas Huebler, ‘Artist Statement’ in Konrad Fischer and Hans Strewlow, Prospect 69, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1969, p. 29. ↩

-

Robert Rooney, Project 8: Robert Rooney, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1975. Quoted in David Homewood, ‘RR/SK: Public Exhibition’, Discipline, vol. 2, 2012, p. 99. ↩

-

Homewood, ‘RR/SK: Public Exhibition’, p. 101. ↩

-

Virginia Coventry (ed.), The Critical Distance: Work with Photography/Politics/Writing, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1986, p. 47. ↩

-

‘Society for Other Photography’ in Australian Perspecta: A Biennial Survey of Contemporary Australian Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1983, p. 93. ↩

-

Paul Taylor, ‘Popism’, Popism, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1982, p. 2. ↩

-

Mathieu Gallois, ‘Flight 934-B’, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, 2000, https://ccp.org.au/exhibitions/all/flight-934-b. Accessed 12 June 2019. ↩